Design Pattern Principles

Design patterns are governed by two design principles.

Design Pattern Principles

The Gang of Four (GoF) cataloged 23 Object-Oriented (OO) Design Patterns, which are mostly comprised of combinations of basic OO components, but these components are not applied randomly. There are repeating component configurations for the design patterns, which emerge from two design principles in their book:

- Program to an interface, not an implementation

- Favor object composition over class inheritance

Principles are guidelines. They are not rules that must always be followed. They are suggestions that lead toward good design choices, but they do not need to be universally applied. As with most principles, it takes experience to determine when to follow a principle and when to ignore it.

It took me a while before I fully appreciated the wisdom in these two design principles. Sometimes they require additional context to be fully appreciated. Here is an interview from 2005 where the GoF talk about both principles to gain some additional insights in their own words.

Program to an interface, not an implementation

When most developers first learn how to code in OO programming languages, they tend to acquire references to the classes directly, often via a class constructor by calling the new operator. This works fine, but code that calls new directly will be tightly coupled to that class.

This is usually okay for some classes such as utility classes – String or Date. But for classes that represent business domains, acquiring objects via new directly may not be the best practice due to that tight coupling.

The GoF are big fans of encapsulation. In addition to keeping class implementation details encapsulated via private field attributes and methods, they advocate keeping the class type itself encapsulated.

In this principle, the GoF are advocating that instead of object references to concrete classes, code should have references to their interfaces. It’s subtle, but there’s a distinction between references to interfaces and references to classes.

SIDE NOTE: The design patterns book and the Java programming language were both released at about the same time. While GoF use of “interface” is not a direct reference to Java interfaces, it’s still consistent. The GoF also consider abstract base classes as interfaces in their principle as well. Erich Gamma presents some reasons why he prefers an abstract base class over an interface in the interview referenced above.

An interface defines a contract by declaring a set of method signatures. A contract defines expectations and obligations of the method behaviors declared in the interface without an indication of the implementation. A class that implements an interface contains the code that provides the implementations for those methods.

The client code will still require a reference to a class that implements the interface, but I’ll write about that in an upcoming blog post (See: Dependency Injection).

There are several advantages to following this principle:

- The interface can be defined before the implementation. This provides the interface designer an opportunity to consider the contract before it could be influenced by the implementation.

- The client code only depends upon the contract interface. It’s easier to exchange one implementation for another. It’s even possible for the client code to be unaware of the implementation class or its type.

- Once an interface is stable, client code accessing that interface and the concrete class implementing that interface can be implemented in parallel even by different developers or teams. The interface is a boundary the separates to these two concerns.

- The client code can be unit tested with test doubles that emulate the interface contract independently of the implementation.

Favor object composition over class inheritance

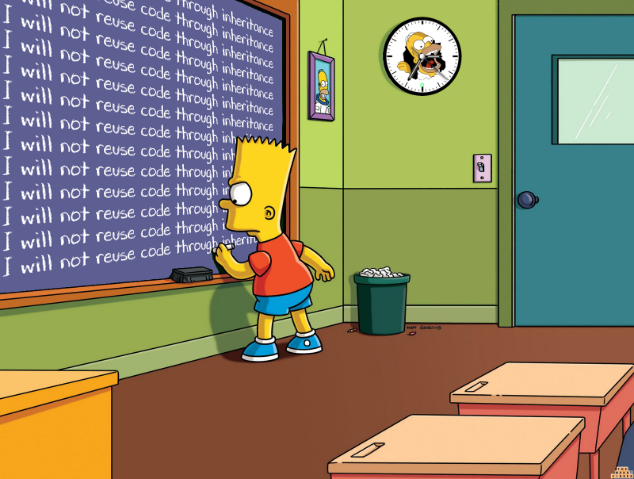

This principle seems contrary to one of a fundamental OO component – inheritance. I would argue that inheritance was a major factor in convincing developers to use OO. We could finally achieve code reuse in a way that was part of the paradigm. But it wasn’t quite the panacea we were hoping for. The reuse was static. Children classes had direct knowledge of and dependencies upon all their ancestor classes. Any changes in the ancestor classes could cause unintended consequences in the descendant classes. And the inheritance family trees could grow huge to the point where you really weren’t quite sure what behavior a child class was inheriting. For clarity, this is class inheritance, which is about inheriting an implementation. It is not about interface inheritance, which is about inheriting method signatures.

Object composition changes the paradigm. We don’t achieve code reuse via class inheritance. We achieve it via objects delegating to one another. This isn’t quite like the traditional divide-and-conquer decomposition. It’s more akin to recursion, but it’s structural recursion, not functional recursion. I’ll present more details about this with compositional patterns.

This principle wasn’t obvious to me. It took me a while to understand it. It took me even longer to appreciate it. Here are some advantages I’ve observed in the patterns that feature this principle:

- Code reuse is configured dynamically at run time. It is not statically defined at compile time. Configuration often happens at start up, but it can be updated at any time.

- Behavior emerges from the composed objects. The same code base can support different compositions each its own customized behavior. This allows the same code base to support bespoke behaviors for customers and even individual users solely through different combinations of the composed objects.

- There’s not a lot of code required in the plumbing for design patterns that feature this principle. Composition patterns aren’t difficult to design or implement. The difficulty arises in the mental shift of understanding that behavior is distributed across several objects and that it can be configured dynamically.

- Design patterns based upon this principle also tend to be based upon the first principle as well. While behavior emerges from the composition of objects, their classes don’t know nor depend upon each other’s type. The only knowledge and dependency they have tend to be upon interfaces. This separation of concerns allows the design to be modular so that it can easily be updated via new classes added or previous ones removed without affecting the rest of the design. The classes in these designs tend to be easy to unit test as well.

Conclusion

Keep these two principles in mind while learning design patterns. It may help in understanding the choices that are made in their designs. I’ll try to point out the principles when presenting patterns in more detail.

For more of my take on Design Patterns, See: Index of my Design Patterns Blogs and Essential Design Patterns AI Notebook.