Composite Design Pattern - Use Case

Using Composite Design Pattern for Secret Menu Items

Introduction

Composite Design Pattern introduced the Composite Design Pattern, but it was getting a bit too long. This blog continues the story with a Use Case.

Use Case – Can I get fries with that?

This Composite Use Case example is inspired by fast-food burger chains.

Two all-beef patties …

McDonald’s featured a popular Big Mac jingle in its commercials in my youth:

Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun.

It’s such a simple campaign that lists the ingredients of a Big Mac and yet it was so memorable. My generation can still sing it.

McDonald’s was known for its consistency. A Big Mac was, and still is, a Big Mac everywhere. Consistency was even in their advertising by singing its ingredients. It may not be the best burger in the world, but you know what you are getting when you order one.

This didn’t work so well for my family. My father and I were both picky eaters. Onions? Yuck! Pickles? Oof! Don’t get me started with the special sauce that McDonald’s won’t even identify.

When we ate at McDonald’s my father would order a plain burger. I’d order a plain burger with ketchup. My mother would order something off the standard menu. Her order would be ready quickly, and then we waited as customer after customer would order and be served. Fast food was not necessarily fast for us.

Hold the pickle, hold the lettuce …

Then Burger King came to town. They had a different jingle:

Hold the pickle, hold the lettuce,

Special orders don’t upset us.

All we ask is that you let us serve it your way.

Our special orders were always provided quickly. There was no waiting. My family always chose Burger King over McDonald’s when we had the choice.

Can you keep a secret?

In-N-Out Burger offers typical fast-food burger fare, but they also have a secret menu. These are combinations you can request, which won’t be displayed on the menu including:

- 3x3: a triple cheeseburger

- 4x4: a quadruple cheeseburger

- Flying Dutchman: bun-less double cheeseburger

- Protein Style: lettuce wrapped burger

- Animal Fries: fries topped with burger condiments

- Cheese Fries: self-explanatory

- Roadkill Fries: Animal Fries topped with a Flying Dutchman

- And more …

And you can even customize it to some degree, such as a 20x20 shown above.

Fast-food and Software Design

These three burger joints are metaphors for several software design approaches:

- McDonald’s is like a traditional OO design. A Big Mac is well defined. It’s well implemented. But if you want something different, prepare to wait. It’s like the Project Manager asking for a simple feature and being told that it will take 6 months.

- Burger King is like the Decorator design pattern. The core feature is a burger on a bun. The condiments are the decorators. Any configuration of burger and condiments is as easy to produce as any other.

- In-N-Out Burger is something completely different. There is no core feature of a burger on a bun. Decorator isn’t quite the right fit. Some secret menu items omit the burger, and some omit the bun. And customers can customize something that’s not on any menu. In-N-Out Burger is like the Composite design pattern.

Composite à la In-N-Out Burger

Composite is a structural design pattern. It’s more about the organization of objects than it is about behavior. Behavior is additional context that needs to be added when considering Composite. Since Composite is mostly behavior independent, we can choose almost any behavior we desire for which the Composite structure is a good approach.

The behavior will tend to be reflected in the Component’s definition as well as the Composite’s implementation. While Composite will almost always feature iterating through a list of Components, what it does while iterating will vary based upon the behavior.

There are at least three possible behaviors that come to mind for In-N-Out Burger:

- A label of the ingredients of a food item. This is similar to what was show in the Decorator/UseCase.

- The total price for a food item, which would be the sum of all prices of the individual ingredients.

- The total calorie count for a food item, which would be the sum of calories of the individual ingredients.

The Composite design can handle any of these and even all all three. This use case will focus upon a calorie count feature.

How many calories are in each food item? The interface at the top of the design only needs to declare this:

interface FoodItem {

int getCalories();

}

This won’t be a complex design, but it will take up some space. I’m going split the design into multiple diagrams.

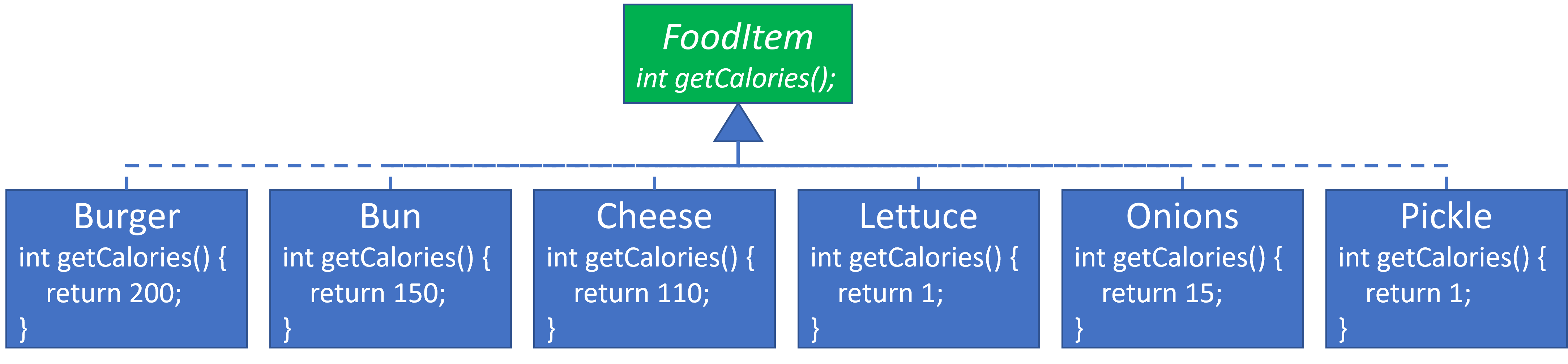

Leaf Food Items

Let’s start with the Leaf food items, and I don’t just mean lettuce. These will be the component parts available at In-N-Out Burger from which all possible combinations of foods can be assembled. Each will return how many calories are in them individually. This is not a complete list of ingredients, but it should be sufficient to convey what’s needed:

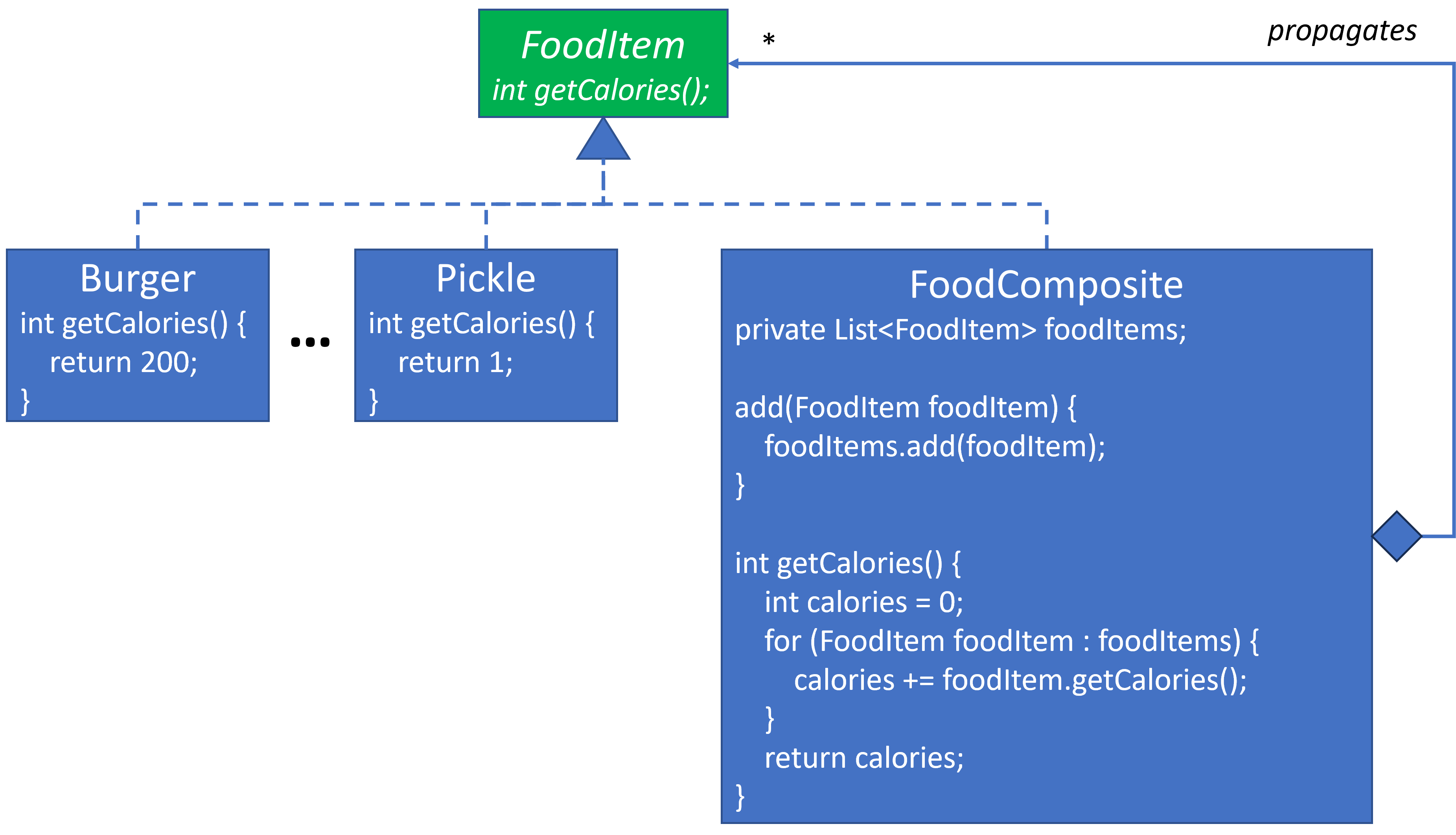

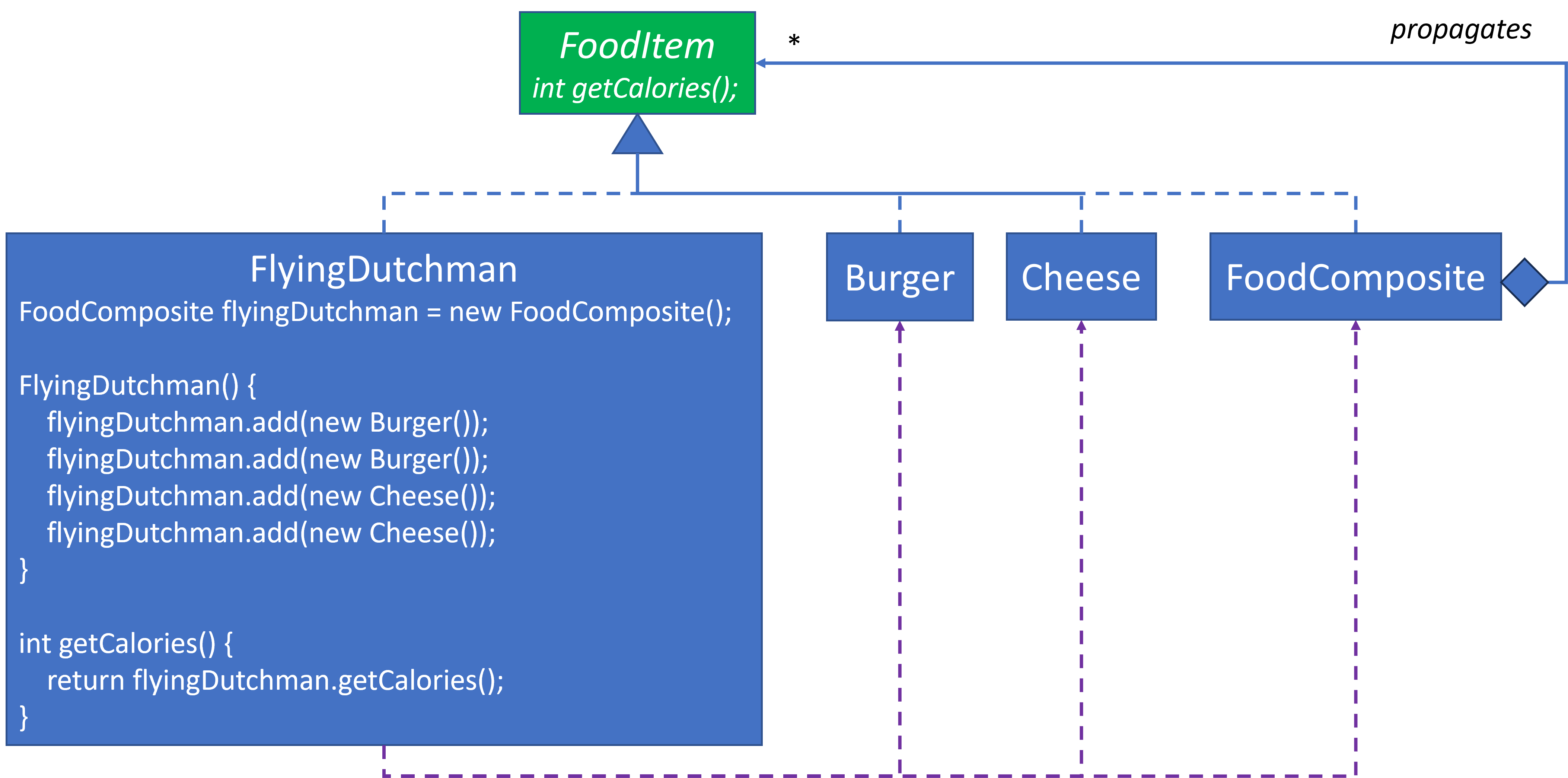

Food Composites

This diagram adds FoodComposite to the design. It’s a list of FoodItems, and it obtains the total calorie count by summing the calories in each FoodItem. Burger and Pickle remain on this diagram to highlight how the Leaf FoodItems and FoodComposite reside in the same design, but none of these concrete classes have any dependency upon any another:

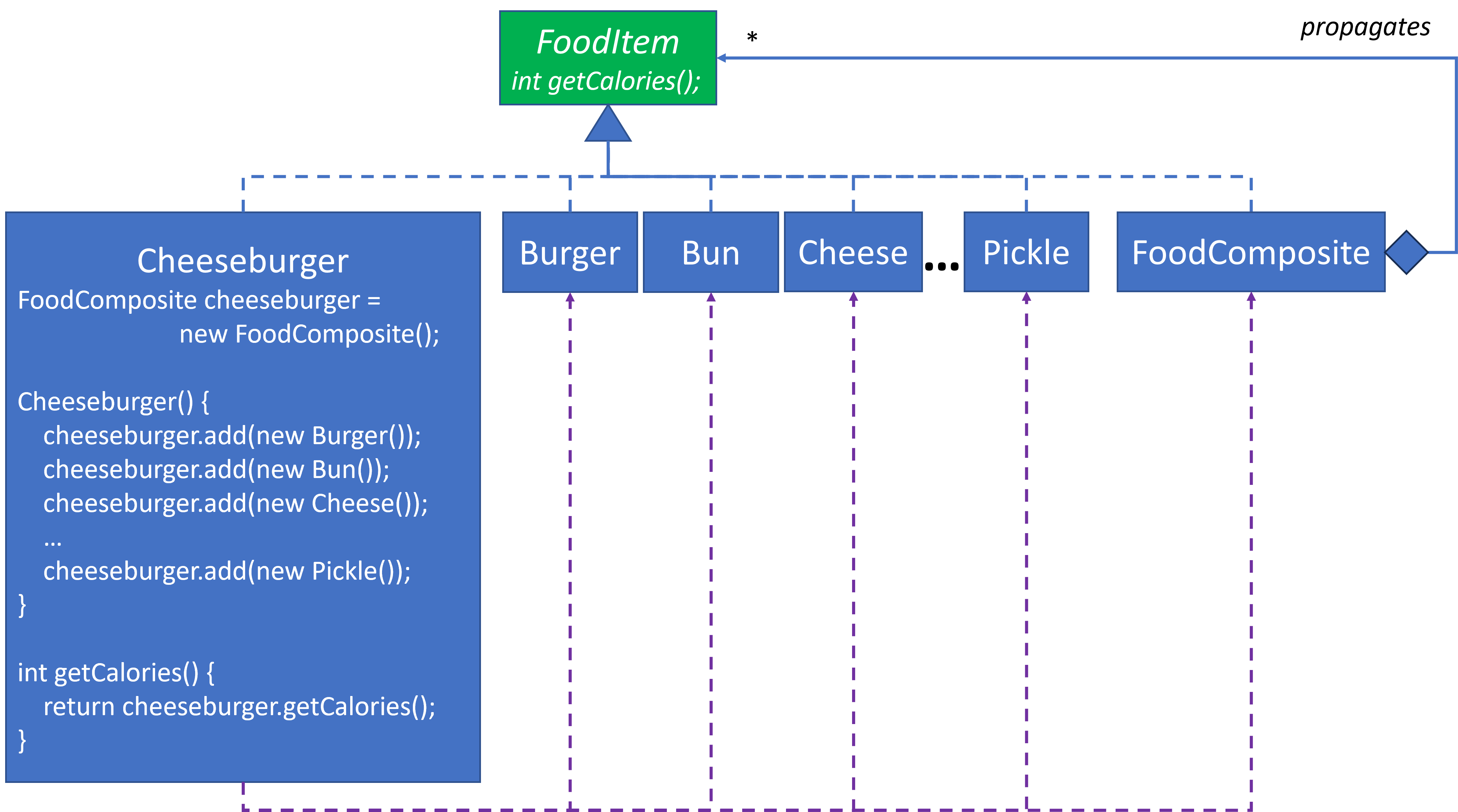

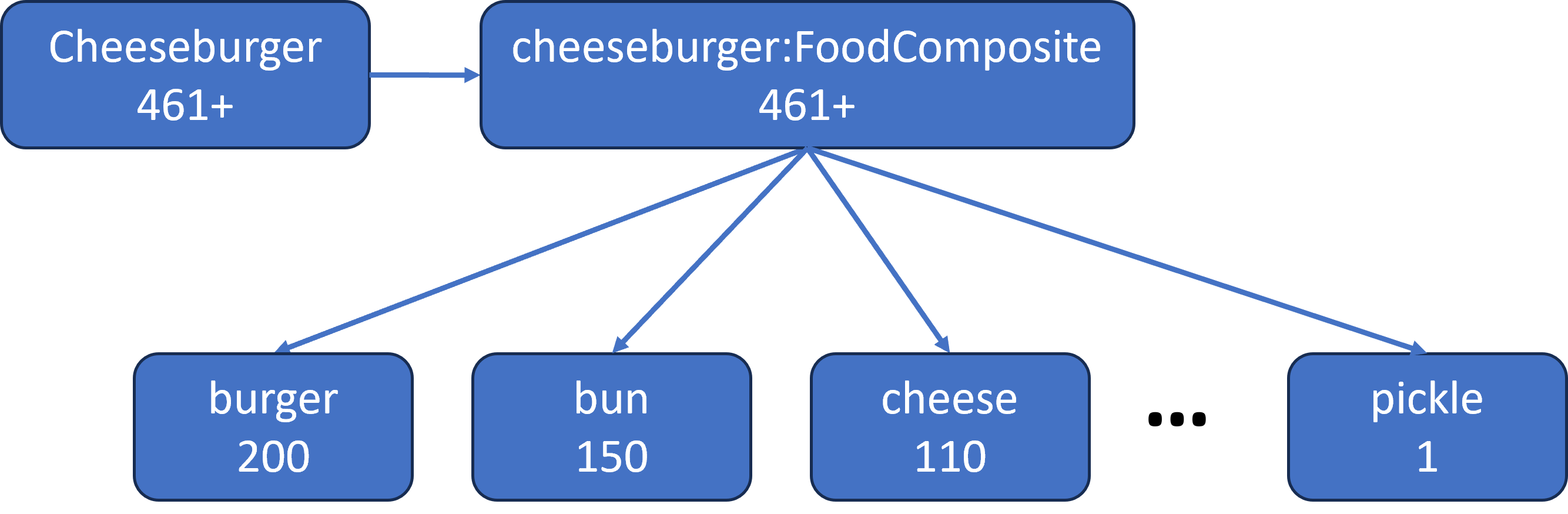

Cheeseburger

The Cheeseburger gets interesting. I could have made it a more traditional design where the Cheeseburger class had field attributes for Burger, Bun, etc. I decided to leverage FoodComposite instead.

I could have also had Cheeseburger extend FoodComposite, but I decided not to for two reasons:

- The delegating approach is more in line with favoring object composition over inheritance.

- If

Cheeseburgerwere aFoodCompositethen moreFoodItems could be added to it. For now, I wantCheeseburgerto remain a well-definedCheeseburgerthat cannot be further modified by adding moreFoodItems to it. If we wanted to be able to modify aCheeseburger, then there are several design options we could choose.

Cheeseburger wears several hats:

- It is a leaf

FoodItem. - It is not technically a

FoodCompositebut it contains aFoodCompositeand delegates to it. - It’s a

Configurer. Cheeseburgerhas no functional behavior in its implementation. It creates and assemblesFoodItems, adds them to aFoodComposite, and finally delegates to theFoodCompositefor its calorie count.

Its composite tree would be:

Each line represents the a call to getCalories():

Cheeseburgerdelegates to thecheeseburger:FoodCompositeto get its calorie count.cheeseburger:FoodComposite’s calorie count is the sum of itsFoodItems.- Each leaf

FoodItemreturns its calorie value. - The final

Cheeseburgercalorie value will be the sum of the leaf node calories. - The number in each object node shows the value returned from

getCalories()for that object. The+indicates that there are more calories for theFoodItems not shown, such asTomatoandLettuce.

This same propagation strategy replicates in the subsequent object trees, so I won’t repeat the verbiage.

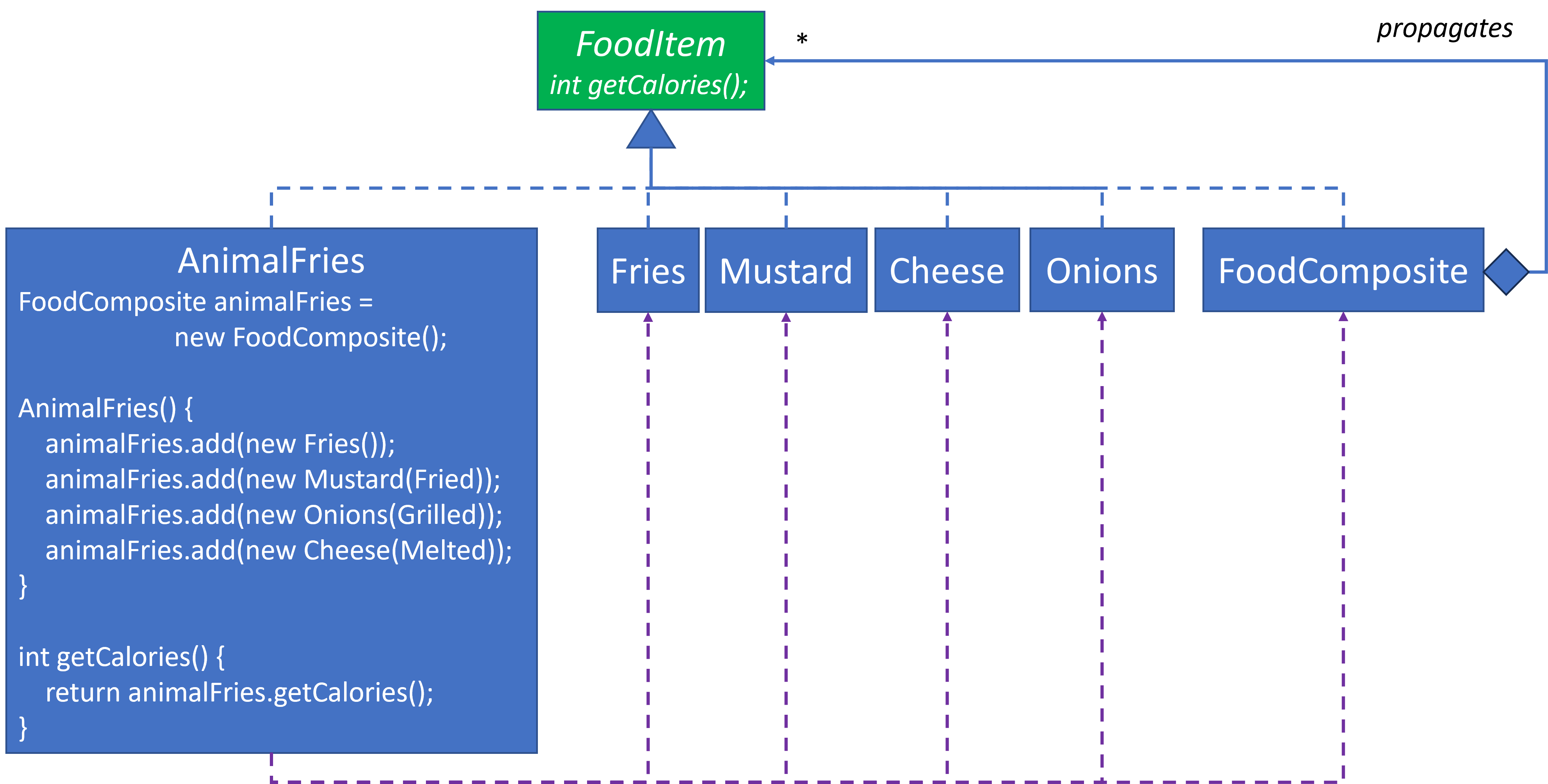

Animal Fries

Animal Fries follows the same Cheeseburger design:

Its composite tree would be:

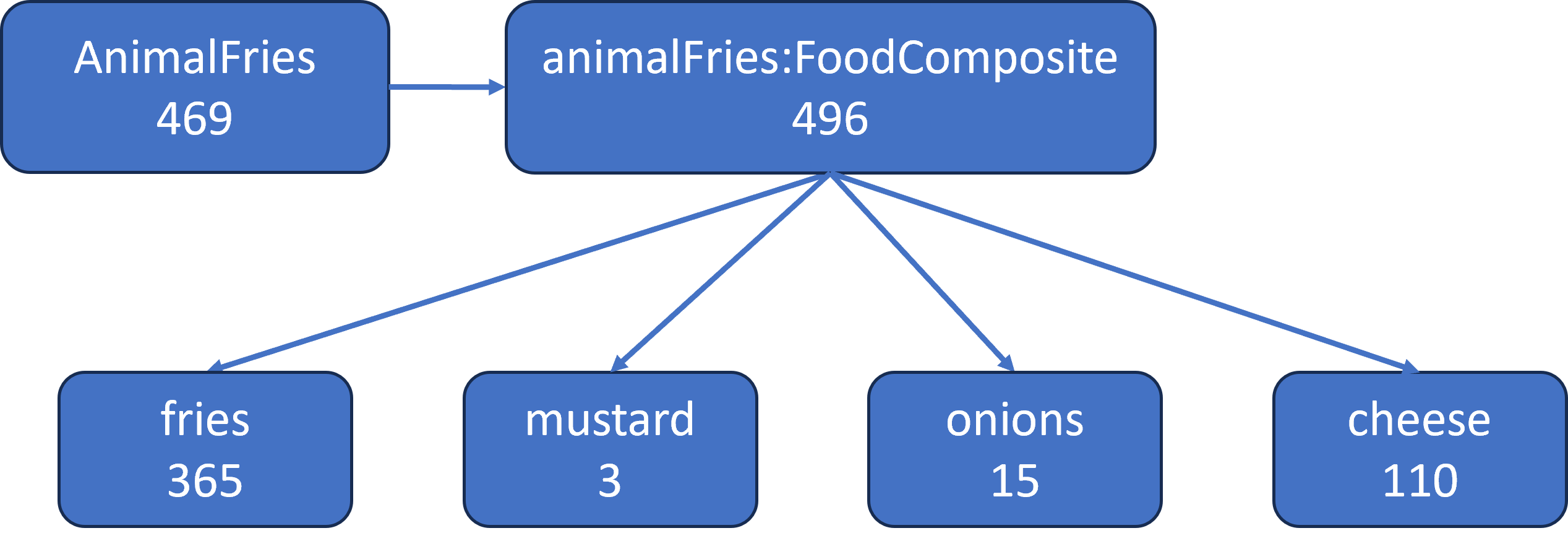

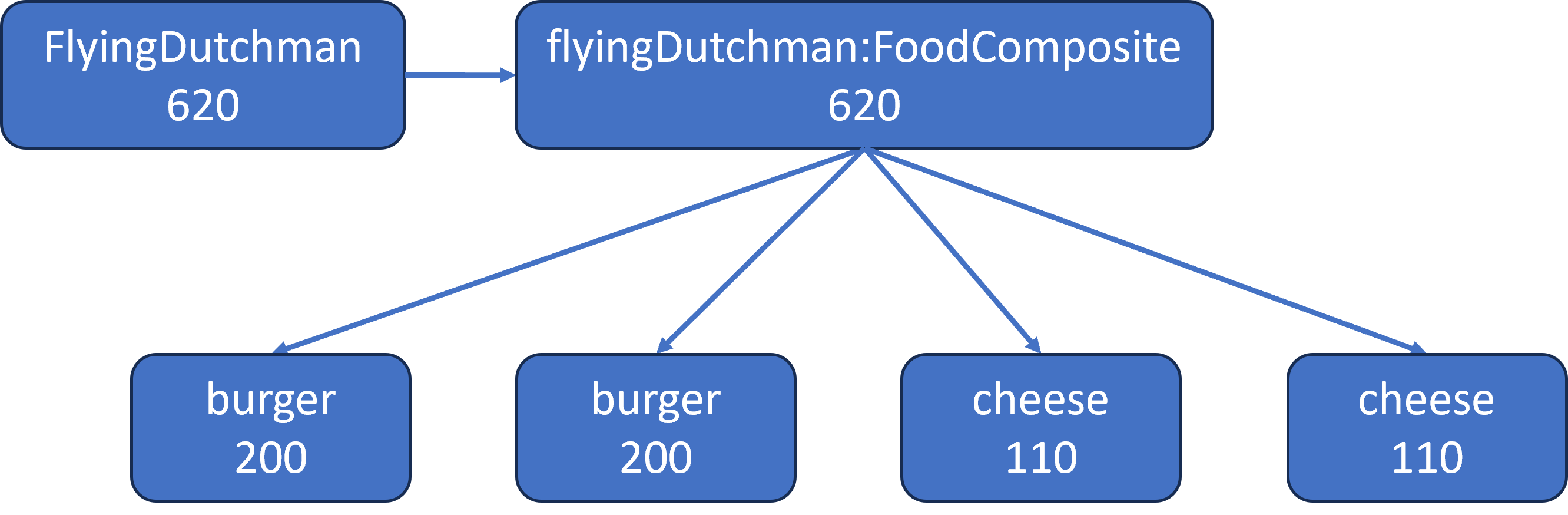

Flying Dutchman

Flying Dutchman will do likewise:

Its composite tree would be:

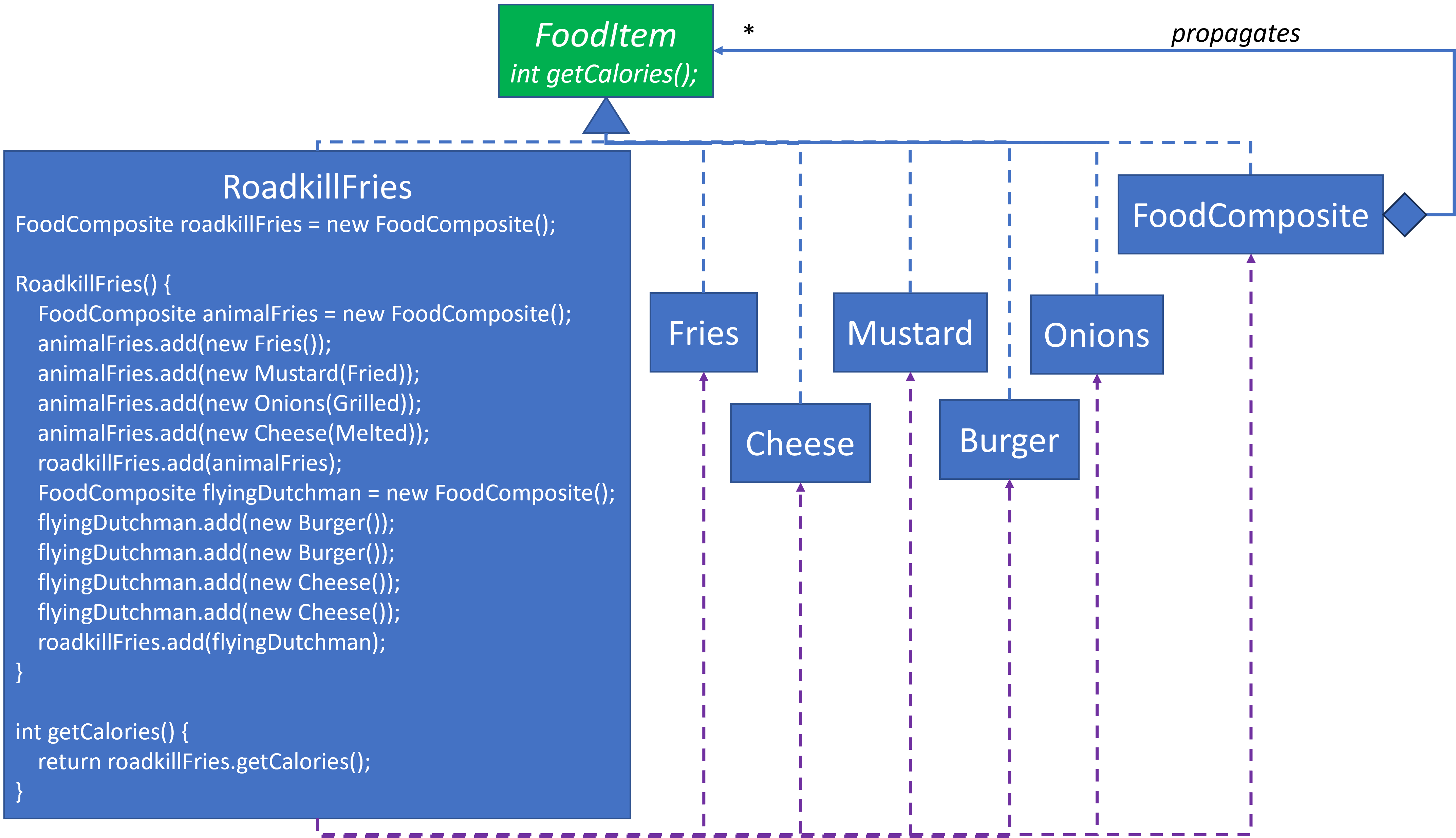

Roadkill Fries

Roadkill Fries are Animal Fries topped with a Flying Dutchman. There are a couple ways to handle Roadkill Fries.

Roadkill Fries Part 1

Roadkill Fries can follow the same design as the previous examples:

It’s composite tree would be:

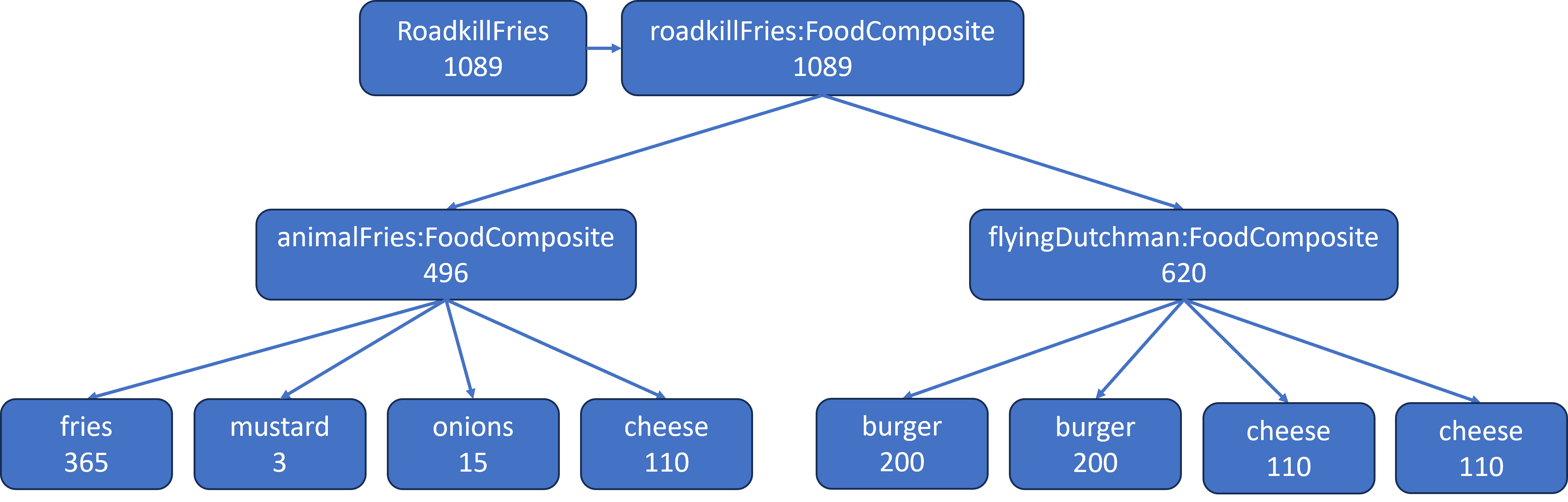

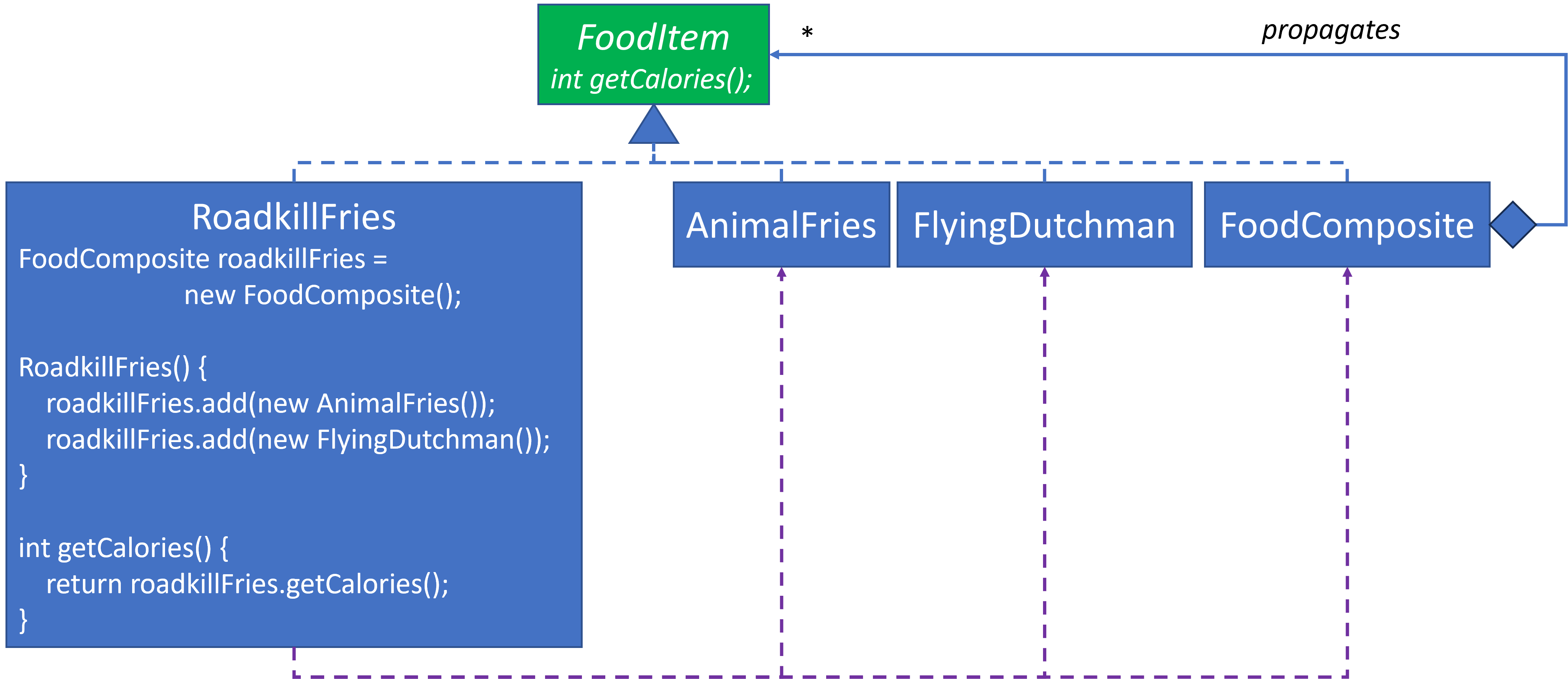

Roadkill Fries Part 2

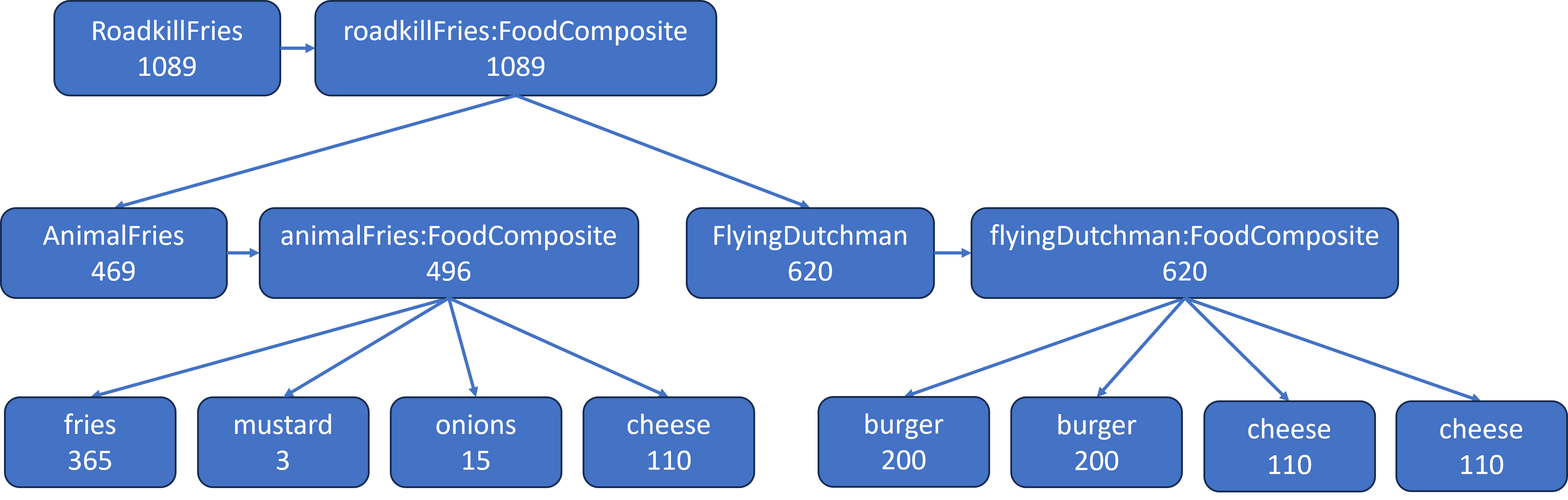

However, we don’t have to duplicate menu item definitions. We can build Roadkill Fries from the composites we already have:

AnimalFriesandFlyingDutchmanareFoodItems, and that’s all we need to designRoadkillFries.- Each concrete class implements

FoodItemand delegates toFoodComposite.

Its composite tree would be:

Learn the rules, and then break the rules

I’m not really breaking the rules here, but I’m really pushing the Composite boundary a bit.

The previous In-N-Out Burger design examples are hardcoded. Each secret menu item requires its own class. It’s not a difficult class to implement, but it’s not necessarily a flexible design either.

Let’s assume that In-N-Out Burger Corporate wants a more dynamic secret menu. They want the ability to add, update or delete secret menu items at any time.

Corporate manages a Secret Menu Specification. It will be of the form:

3x3 => Burger|Burger|Burger|Cheese|Cheese|Cheese|Bun|Lettuce|Tomato|Onions|Pickle4x4 => Burger|Burger|Burger|Burger|Cheese|Cheese|Cheese|Cheese|Bun|Lettuce|Tomato|Onions|PickleFlyingDutchman => Burger|Burger|Cheese|CheeseProteinStyle => Burger|LettuceAnimalFries => Fries|Mustard|Onions|CheeseCheeseFries => Fries|CheeseRoadkillFries => AnimalFries|FlyingDutchman

The software at the In-N-Out Burger locations should support these and only these menu items, both regular and secret.

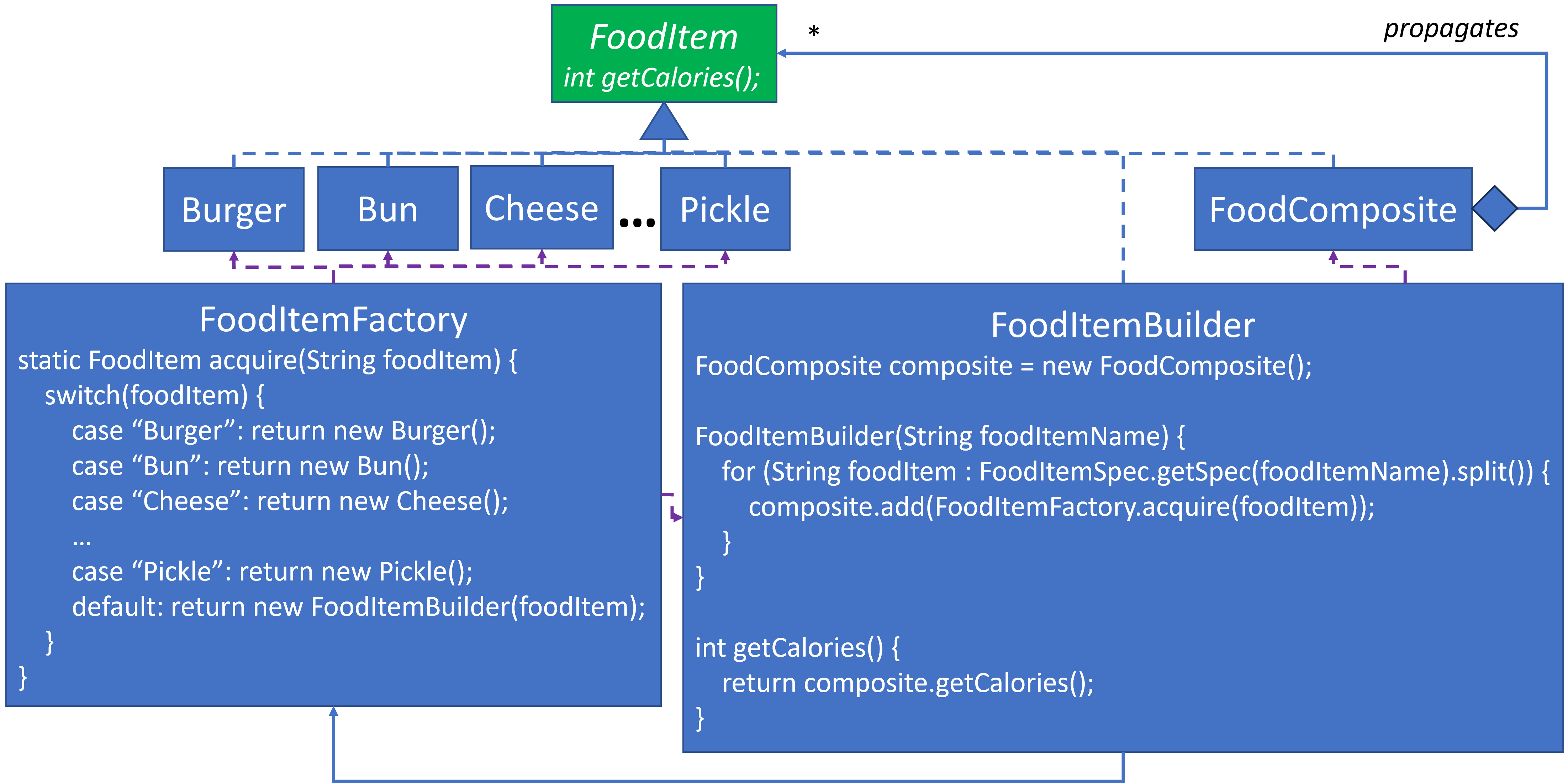

Here’s a flexible design with explanation following:

This is still a Composite design at its core. The individual FoodItem classes for Burger et al. are unchanged in this design from the previous ones. They are so simple that they apply as-is even when making a significant change such as this one. The specific hardcoded menu items are no longer present in this design as individual classes.

Two new classes have been added to replace the previous hardcoded menu item classes: FoodItemFactory and FoodItemBuilder.

A Simple Request

Let’s start with the most basic request with a request for a Burger. It would look like this in code:

FoodItem foodItem = FoodItemFactory.acquire("Burger");

FoodItemFactory’s switch statement would match on “Burger” and return a new Burger instance.

A More Complex Request

Let’s consider this:

FoodItem foodItem = FoodItemFactory.acquire("ProteinStyle");

Unlike the previous example, FoodItemFactory won’t find a match for “ProteinStyle”. Its default behavior will return a FoodItem from the FoodItemBuilder for “ProteinStyle”. The FoodItemBuilder is a generic version of the hardcoded designs above such as AnimalFries and FlyingDutchman. The previous classes and this new FoodItemBuilder class have the following in common:

- They all declare a

FoodCompositefield attribute. - They all implement

getCalories()by returning theFoodCompositefield attribute’sgetCalories(). - They all populate

FoodCompositewith otherFoodIteminstances. The difference is that the previous design hardcoded the component construction, whereas this design retrieves the specification in the form of the list ofFoodItems, which it resolves via theFoodItemFactory. - I didn’t have enough room to show the

FoodItemSpecclass. Its method will use the mapping examples shown above to return the list ofFoodItems for any secret menu item.

Since ProteinStyle is defined as ProteinStyle => Burger|Lettuce, FoodItemBuilder will iterate the ingredients with “Burger” and “Lettuce”. It will obtain a Burger and Lettuce instance from FoodItemFactory and add them to the FoodComposite.

Hey, Watch This

Now consider this:

FoodItem foodItem = FoodItemFactory.acquire("RoadkillFries");

RoadkillFries are defines as:

RoadkillFries => AnimalFries|FlyingDutchman

When FoodItemBuilder acquires a FoodItem for each of these two from the FoodItemFactory, it will encounter the default case for both, which will build two new FoodItemBuilder, but this time for “AnimalFries” and “FlyingDutchman” separately. They are defined as:

AnimalFries => Fries|Mustard|Onions|CheeseFlyingDutchman => Burger|Burger|Cheese|Cheese

Each new FoodItemBuilder will acquire the specification and iterate each of the elements each of which can now be found in FoodItemFactory switch statement, and the recursion resolves.

Caveats

I didn’t have enough room for edge cases. Production quality design would require exceptions when Strings are not found.

Beware of bugs in the above design; I have only proved it correct, not tried, or tested it.

Flexibility

This design is quite flexible. In-N-Out Burger Corporate could easily add this to their secret menu:

BigMac => Burger|Burger|SpecialSauce|Lettuce|Cheese|Pickles|Onions|SesameBun

More Configuration Options

There are several Creational Design Patterns that help to build composites such as Builder and Prototype.

Summary

This Use Case shows how Composite can accommodate In-N-Out Burger’s Secret Menu, but it could accommodate the regular menu as well, plus customer customization.

Predefined regular and secret menu items could be in the employee display. Or they could be on a store kiosk or mobile app. The displays could also allow customers to customize their order as well.

References

See: Composite Design Pattern/References.