Suril, the Semaphore and Me

My theory-to-practice test double epiphany

Introduction

My first unit test and test double experiences had mostly been through self-study. It looked promising, but was it something that looked good in theory but was too cumbersome to use in practice?

I experimented by creating unit tests for my design pattern examples which worked well. But the implementation and tests were limited in scope, well defined problems, and I already knew them inside and out. Would the same unit test techniques work for production code?

I had mostly been doing research and training at work, and I wanted to get into the development trenches once more. I did several embedded rotations with different teams for the following reasons:

- What problems were the development teams really facing?

- Did these testing practices work in practice?

- Could I transfer what I had learned more effectively by example rather than presenting PowerPoint slides in a two-hour training session?

This is a true story, maybe embellished a bit, but still true. I’ve cleared it with Suril.

Suril, the Semaphore and Me

Suril was a tester with the first team on my embedded rotations. He was a junior developer, and I had known him since his summers as an intern.

We paired together adding test coverage to existing code. I was pleased with how much progress we were making. I felt he understood the process as we were applying it.

Code Coverage should NOT be a Management Metric

Our progress was guided by code coverage. Code coverage is a tool to identify code without tests. Code without coverage is an indication to developers that there is no automated test confirmation. Change that code, potentially introducing a fault, and no test will catch it.

Code coverage should not be a metric or target used by management. Management should not dictate minimum code coverage. As pointed out in Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

When coverage is dictated by management, developers will focus upon coverage, possibly with tests that are low quality. The only thing worse than lack of testing is poor testing. This only creates the illusion of test security.

Developers should strive toward 100% coverage regardless of management mandates. Code without coverage is code without verification. Would you feel confident if your mother’s pacemaker’s recent software update only had 95% coverage? What if her life depended upon the uncovered 5%?

When code is not covered, developers should ask themselves:

- Is there a missing test scenario that will cover this code?

- Is this code that cannot be covered? This does happen occasionally, but lack of coverage should be unavoidable rather than an oversight.

- Is this dead code? Was it implemented before fully understanding the problem, and it’s part of a scenario that never happens? Rather than adding coverage to dead code with an artificial test scenario, can the dead code be removed?

The Semaphore

Suril and I had covered a significant portion of the code, but we still had a block of uncovered code containing a Java Semaphore and its tryAcquire(...) method. The Semaphore/tryAcquire(...) was deep in the implementation and being used for concurrency management. Concurrency is difficult to implement correctly and challenging to test.

The Semaphore related code was like the following:

class SoftwareUnderTest {

private static Semaphore semaphore = new Semaphore(10);

public void doSomething() {

try {

if (semaphore.tryAcquire(30, TimeUnit.SECONDS)) {

// Proceed since a permit has been acquired.

} else {

// Adjust since a permit was not acquired within allotted time.

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Take action since there was an interrupt exception.

}

}

}

I’ve not included the implementation details, since I don’t remember one iota of what we were doing except that it contained the Semaphore dependency.

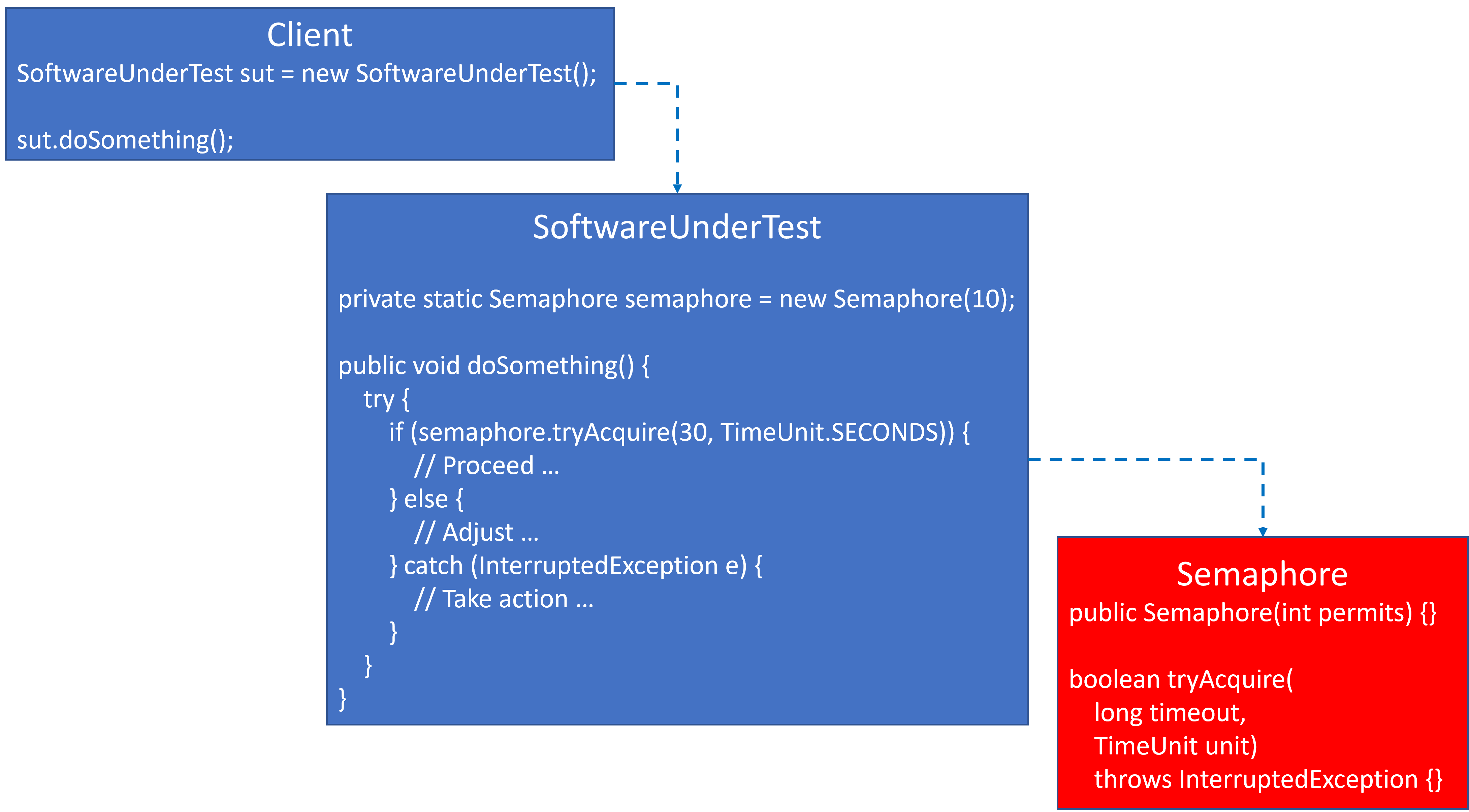

Here’s the design, which highlights the main design issue. All dependency and knowledge flows from the Client through the SoftwareUnderTest and into the Semaphore, which I’ve shaded red to highlight that it’s an external dependency. Everything in this design depends directly or indirectly upon Semaphore.

It was near the end of the day, we were tired, and we didn’t have the mental stamina to tackle this in the last hour of the day. Suril and I brainstormed a bit before calling it a day. Several ideas included:

- Overriding the 30 second timeout to make it shorter – much shorter to possibly milliseconds. 30 seconds would be way too long for testing runtime.

- Creating enough concurrently running

Threads such that some would acquire the permits while others would have to wait. - Injecting sleeps into the

Threadso that the timing would be just right for some threads to acquire a permit immediately while others block-waited and then get their permits after the previous ones released them while others timed out having never received their permits. This would have to be coordinated with the overridden timeouts. Even if we got this to work, I was concerned that the tests could be flaky. That is, sometimes the tests pass, and sometimes they fail. - We had no idea how to force an

InterruptedException.

I spent the evening and a part of the night mulling over these ideas in my head.

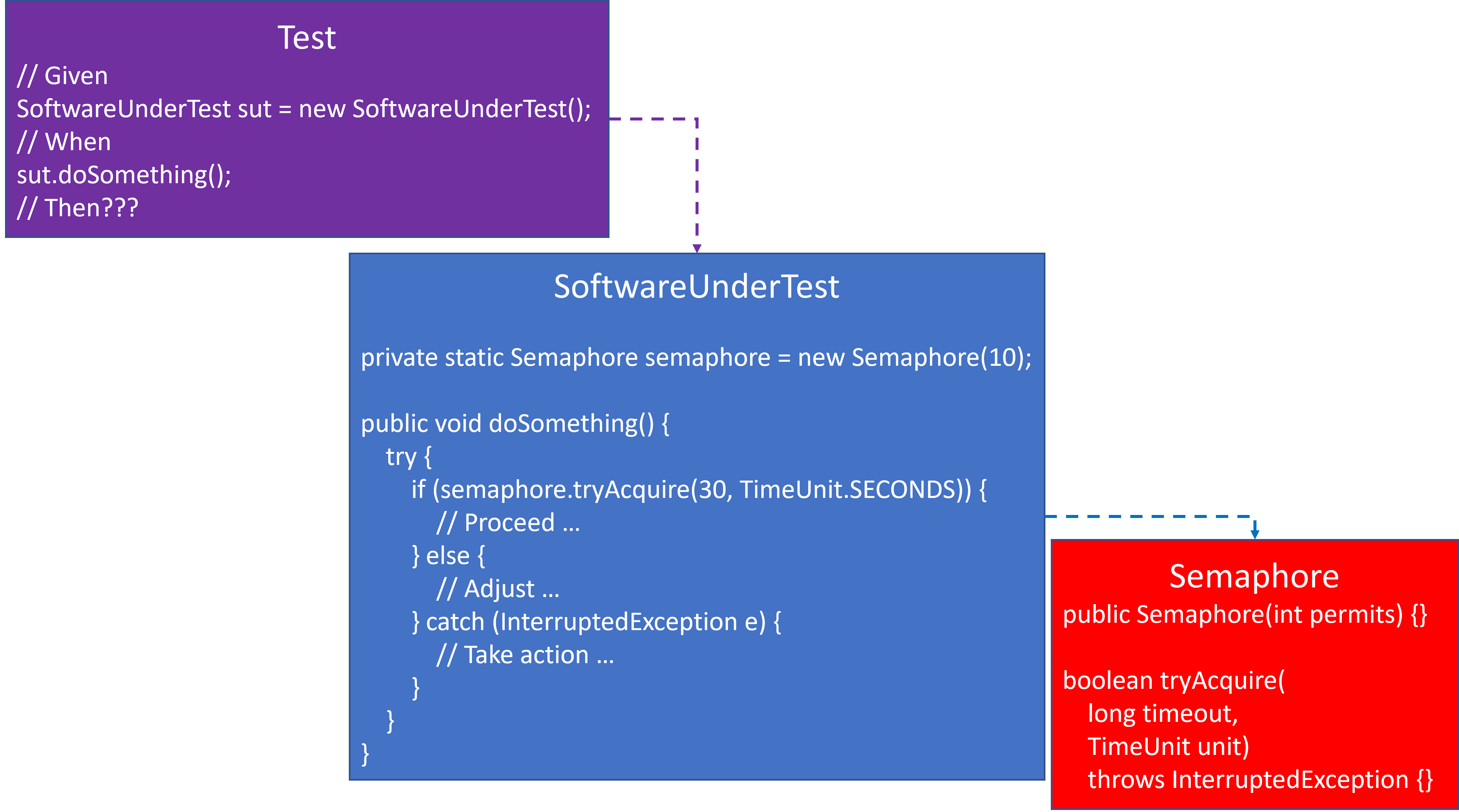

This diagram highlights why we were struggling with developing a test plan strategy:

- The

Testalso depends upon theSemaphoreindirectly. - The

SoftwareUnderTestbehavior is tightly coupled toSemaphoreand depends upon behavior provided bySemaphore.Testcannot access or influence theSemaphoreembedded withinSoftwareUnderTest. Therefore, there’s no easy way to get theSemaphoreto do what we want it to do to confirm the SUT.

The Most Fruitful Stand-Up Meeting of my Career

At our next morning’s stand-up, I was up first and reported that Suril and I had made test good progress. We still had a section of code to cover. It was going to be challenging. It would probably take at least half a day or the entire day to confirm the rest.

As others reported their status, my mind wandered as it is wont to do when I’m not too engaged in the current activity.

Then I had an Aha! idea. It was a Eureka! moment. I knew how to test everything. It wasn’t nearly the challenge Suril and I had imagined.

This was probably the most fruitful stand-up meeting of my career, but that’s not too high of a bar to clear.

What Are We Really Trying to Test?

I pulled Suril to the side as soon as the meeting was over. I told him that I had an idea for how we could test the code much easier.

All our ideas about changing the timeout to make it shorter, creating and managing a set of Threads and the InterruptedException issue were all valid test considerations, but only if we were testing Java’s Semaphore. We don’t need to test Semaphore. The Java team has done that. If we can’t depend upon Semaphore’s working as expected, then we have bigger issues.

We only need to test how our code reacts to what Semaphore does.

What Does a Semaphore Do?

Suril and I didn’t need to become experts on Java’s Semaphore. We just needed to understand boolean tryAcquire(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptedException well enough to emulate its behavior.

From what we could tell the method only did three things:

- Return

truewhen it could acquire a permit. - Return

falsewhen it could not acquire a permit within the timeout period. - Throw an

InterruptedExceptionwhen interrupted.

We only needed to create tests that confirmed that our code performed the expected behavior for each of these three tryAcquire(…) cases.

A Minor Refactoring to Introduce a Test Seam

We could not easily test our implementation in its current form. It was obdurate to have testing added to it. Legacy code is often obdurate to testing.

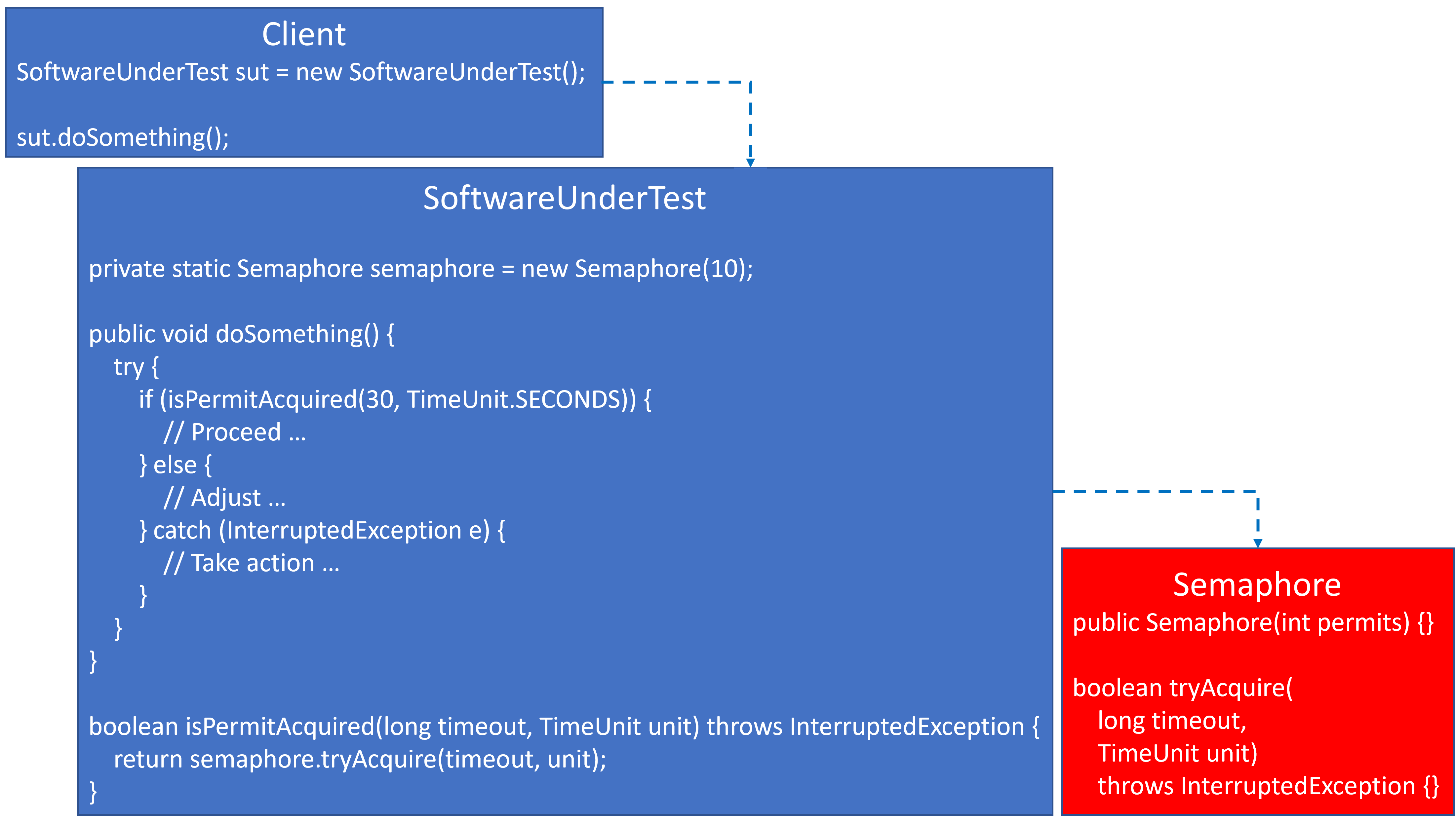

The method implementation was tightly coupled to the Semaphore. It calls tryAcquire(…) directly. We needed to refactor the implementation safely so that it would be not quite as tightly coupled. We used the Extract Method refactoring to isolate tryAcquire(…). Notice that the new extracted method, isPermitAcquired(…), is package-private. We will need this in testing soon. I also renamed the extracted method here, since I feel it’s more descriptive in the context of its use:

class SoftwareUnderTest {

private static Semaphore semaphore = new Semaphore(10);

public void doSomething() {

try {

if (isPermitAcquired(30, TimeUnit.SECONDS)) {

// Proceed since a permit has been acquired.

} else {

// Adjust since a permit was not acquired within allotted time.

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Take action since there was an interrupt exception.

}

}

boolean isPermitAcquired(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptException {

return semaphore.tryAcquire(timeout, unit);

}

}

Here’s the diagram of the change. It looks almost identical to the original design diagram above. In production, we still have the same dependency as before:

However, we’re going to leverage that new extracted package-private isPermitAcquired(…) method in the tests.

Method Override Test Double

At the time, I didn’t have the vocabulary to describe the technique to Suril. I basically had to show it to him. But now I have the vocabulary with some diagrams.

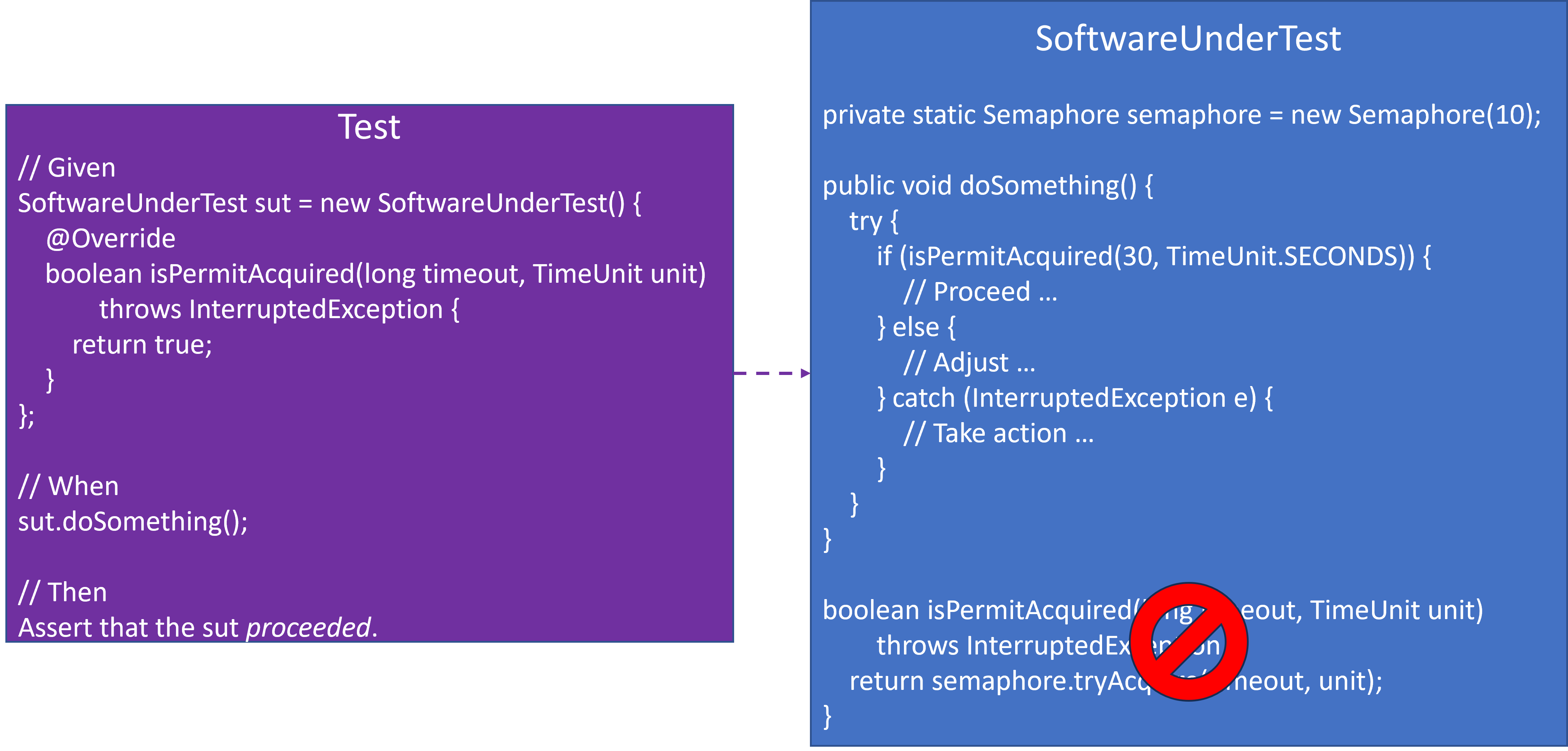

Suril and I were able to carve off a little bit of the SoftwareUnderTest and replace it with a Test Double method that allowed us to inject the behavior we desired. We used the Method Override Test Double technique, which I mentioned in the previous blog, which described the steps. I’ll continue here with the Semaphore as an example.

Our Test Double was not a separate class as it was for most of the examples in Test Doubles. Our Test Double was the package-private isPermitAcquired(…) method, which we were able to override in the test and inject whatever behavior we desired. By being package-private, our tests, which were in the same package could access it, but classes outside the package could not.

Proceed Test

We overrode the package-private isPermitAcquired(…) method so that it always returned true. Then we asserted that the SUT proceeded. Assertion details are not provided.

@Test

public void doSomething_Proceeds_WhenAPermitIsAquired() throws Exception {

// Given

SoftwareUnderTest sut = new SoftwareUnderTest() {

@Override

boolean isPermitAcquired(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptedException {

return true;

}

};

// When

sut.doSomething();

// Then

// Assert that the SUT proceeded.

}

When we overrode the package-private isPermitAcquired(…) method, we in essence removed its implementation from SoftwareUnderTest with its tight coupling to Semaphore.tryAcquire(…).

The design diagram shows how this removed the Semaphore dependency during the test with the red NOT ALLOWED symbol over the package-private isPermitAcquired(...). Technically, the Semaphore is still a private attribute of SoftwareUnderTest, but since our test is no longer accessing it, it’s no longer a dependency for the test.

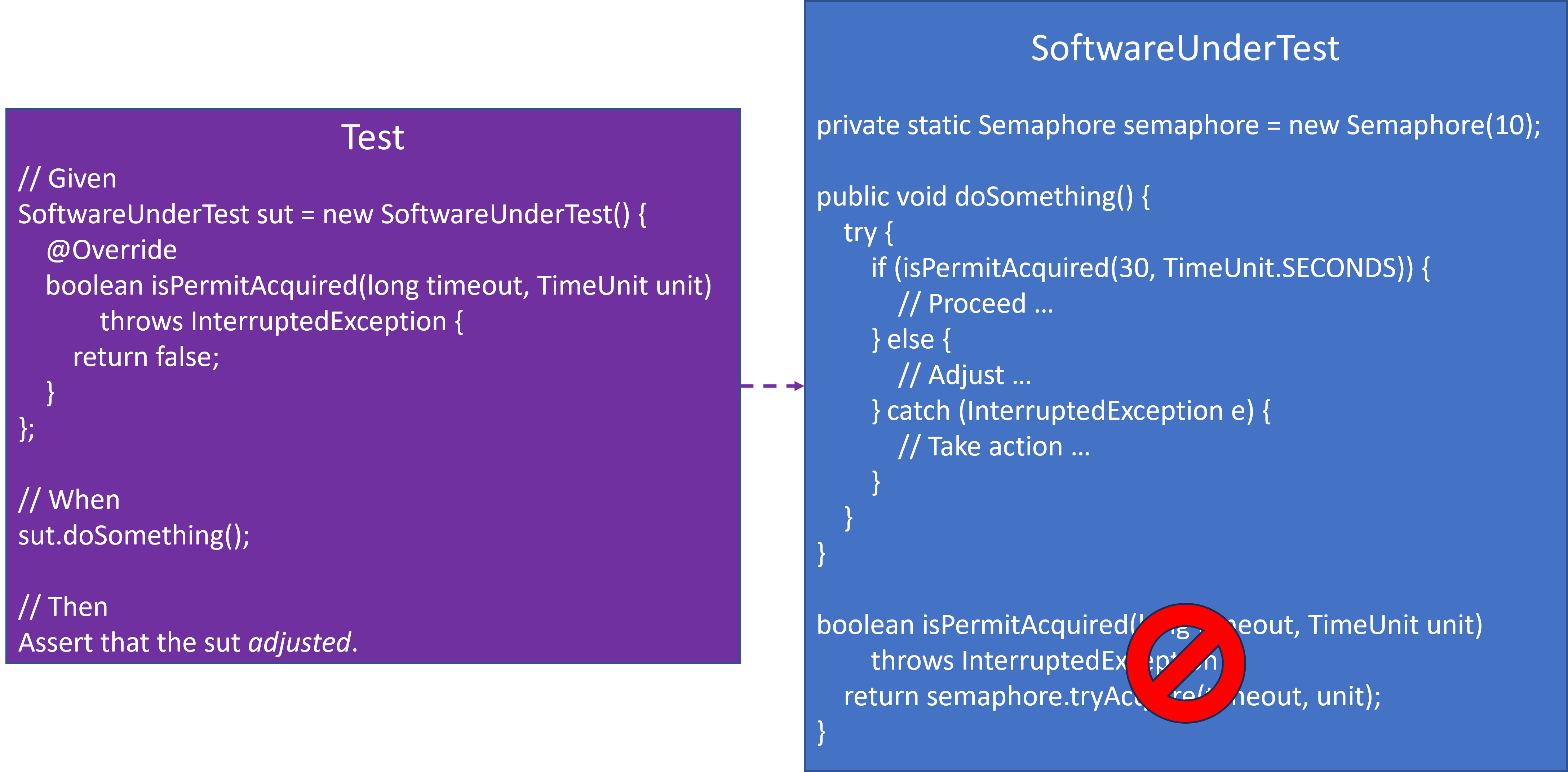

Adjust Test

Our second test was structured the same as the first test, except that isPermitAcquired(…) returned false. This eliminated the concurrent Thread management I had been dreading the evening before.

@Test

public void doSomething_Adjusts_WhenAPermitRequestTimesOut() throws Exception {

// Given

SoftwareUnderTest sut = new SoftwareUnderTest() {

@Override

boolean isPermitAcquired(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptedException {

return false;

}

};

// When

sut.doSomething();

// Then

// Assert that the sut adjusted.

}

The diagram is almost the same as well:

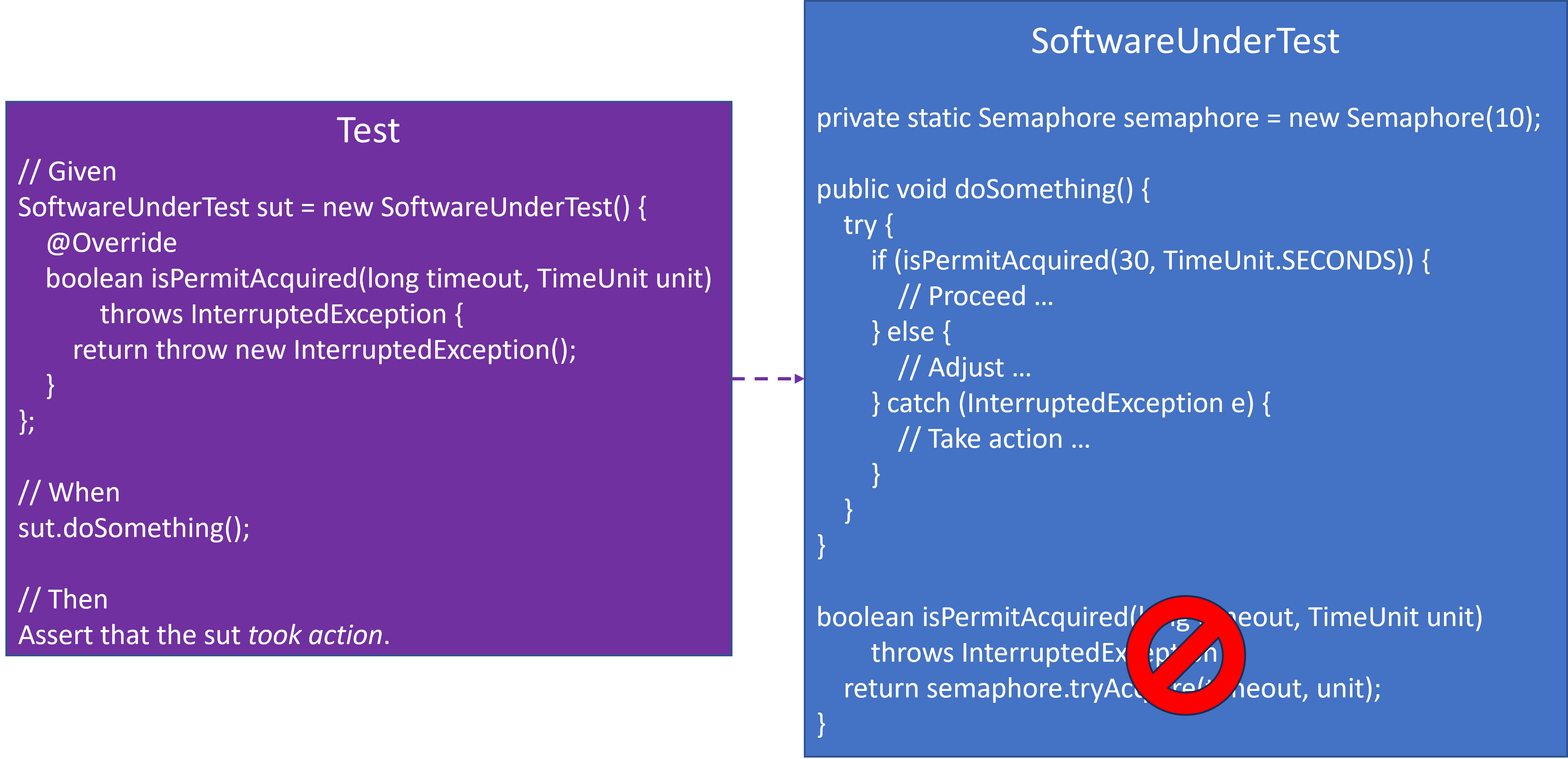

Take Action Test

Finally, for the last test, isPermitAcquired(…) throws an InterruptedException. We had no idea how to force Semaphore to do this previously, but now it’s trivial:

@Test

public void doSomething_TakesAction_WhenPermitRequestIsInterrupted() throws Exception {

// Given

SoftwareUnderTest sut = new SoftwareUnderTest() {

@Override

boolean isPermitAcquired(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptedException {

return throw new InterruptedException();

}

};

// When

sut.doSomething();

// Then

// Assert that the sut took action.

}

Final diagram:

Method Override Summary

Rather than needing half a day to get the tests written and working, it was more like half an hour. We had coverage for everything except the package-protected isPermitAcquired(…) method. And if we had not overridden it in the first test, it might have worked without issues with the package-private isPermitAcquired(...) method.

NOTE: This is an example of the Humble Object Pattern.

However, our efficiency came at a cost. Our tests had implementation knowledge. They were a bit more brittle. But given how few and small they were, we were willing to accept that price.

Summary

While most of this blog provided an example of Method Override to inject a Test Double into the SUT in practice, I wrote it for the lessons I learned with Suril:

- Tightly coupled dependencies aren’t always obvious.

- Releasing yourself from the responsibility of confirming dependency behavior is liberating, and testing becomes much easier. This may have been the first time I truly understood and appreciated the concept of a bounded SUT not directly depending upon its production dependencies.

- Concurrency is always hard.

References

- Previous blog references