Test Doubles

Emulate dependencies without depending upon dependencies

Introduction

I’ve used the term Test Double in several previous blogs with the promise to provide more details:

To isolate the SUT from its dependencies, we override these dependencies with Test Doubles. I’ll provide more details about Test Doubles in the next blog. For now, a Test Double emulates dependency behavior with the Software Under Test (SUT) being none to the wiser. Test Doubles tend to be small snippets of code that emulate a specific dependency behavior that’s only needed within the context of each test.

This is where I follow up upon that promise.

Test Double Raison D’être

Why do we use Test Doubles? Why don’t we test the code as is? Once more I’ll reference my previous blog entry:

We replace production dependencies with Test Doubles mostly because Test Doubles tend to be easier to configure and execute faster in the test than the production dependencies. We also have complete control over dependency behaviors via Test Doubles. It may be very difficult to force behavior in a production dependency. For example, how challenging would it be to force a production dependency to throw a specific exception, such as

OutOfMemoryError, consistently on demand?

In short:

- Configuration convenience

- Test execution speed

- Complete control

The Test Double is not part of the SUT. It is an element of the test configuration that supports the SUT by taking the place of the actual dependency. It’s easy to confuse what’s part of the SUT and what’s a Test Double. I swear that I’ve seen tests that only confirmed Test Double behavior.

The term Test Double is inspired by the term Stunt Double. A Stunt Double is a replacement for an actor in a TV show or movie when the scene is too dangerous for the actor. The Stunt Double is a temporary substitute, who mostly looks like the actor but has special skills. A Test Double is a temporary substitute, that mostly emulates a dependency but has special skills.

Test Double Worthy Dependencies

Almost all software has dependencies, but not all dependencies require Test Doubles in testing. There are no absolute rules. The same dependency may require a Test Double in some tests and none in other tests.

The decision is often based upon what I listed above: configuration, speed and control.

Dependencies That Do Not Tend To Require Test Doubles

Programming language features and language utilities don’t tend to require Test Doubles. I’ve never provided a Test Double for String even if it is technically a dependency.

Value Objects, Data Transfer Objects (DTO), and other relatively small and isolated classes don’t tend to require Test Doubles. They usually require no configuration, they’re fast and they have no external dependencies.

Dependencies That Do Tend To Require Test Doubles

External dependencies, such as databases, file systems, internet calls, time, etc. tend to require Test Doubles. They almost always require configuration. They are slow and difficult to control. They may not handle tests executing simultaneously either.

Project Component Dependencies Can Go Either Way

Dependencies upon other components in the project may or may not require Test Doubles. It depends upon the scenario.

Project components that are relatively small and isolated don’t tend to require Test Doubles. Using them as is confirms more of your system but may require more debugging when tests fail.

Project components that are more complex or have their own external dependencies may require Test Doubles.

As Testing Scope Changes, Test Double Needs Change

The SUT in unit tests are more narrowly scoped and focused. These unit test are shallow. They tend to focus upon one isolated component of the system. They generally don’t dive too deep below the surface of the SUT until they reach Test Doubles. The Test Doubles may often include other components of the system before reaching more traditional external dependencies.

The SUT in integration tests are more broadly scoped and focused. These integration tests are deep. They tend to focus upon the interaction of components of the system. They dive a bit deeper through the interacting components of the SUT until they reach Test Doubles. The Test Doubles may be other components of the system as well, but they may also emulate more traditional external dependencies.

In all test scenarios the Test Doubles define the boundary of the SUT.

Unit testing confirms the components. Integration testing confirms the components work together. I view the distinction between unit and integration testing as:

- Unit testing confirms each individual nut and bolt.

- Integration testing confirms that the bolt screws into the nut.

Test Double Example

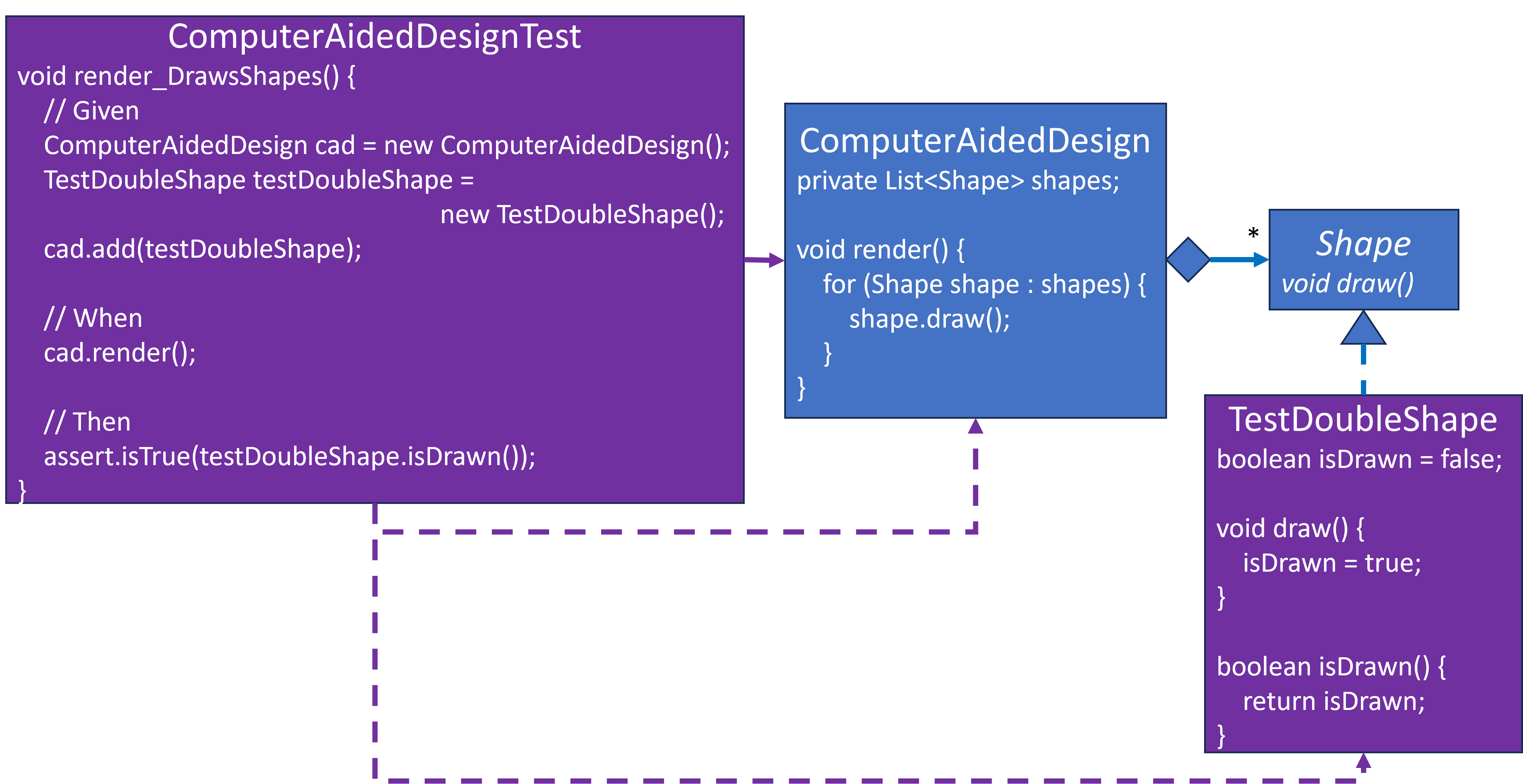

A Test Double is a special case of the Strategy Design Pattern. A Test Double is a specific Strategy implementation, but with the distinction that it exists only for testing purposes. A Test Double even made a cameo appearance in the Testing section with:

Let’s consider how this diagram from nine months ago foreshadowed concepts that I’m writing about now:

ComputerAidedDesignis the SUT. This test confirms that itsrender()method will drawn anyShapes that have been added to it.TestDoubleShapeis a Spy, as mentioned in the previous blog. It implementsShape.draw(), but it doesn’t actually draw anything. Its only behavior is to remember that itsdraw()method has been called and provides a means,isDrawn(), to report that information.ComputerAidedDesignTestis a test class with therender_DrawsShapes()method. It uses the Given/When/Then story telling structure that I mentioned in the previous blog as well:- Given that we have a

ComputerAidedDesigninstance with aTestDoubleShapeadded to it … - When

render()is invoked for theComputerAidedDesigninstance … - Then assert that the added

TestDoubleShapewas drawn.

- Given that we have a

Notice that ComputerAidedDesign and Shape have no arrows pointing away from them. All arrows from purple test related elements to blue application related elements point from purple to blue. This means that the blue boxes have no knowledge nor dependency upon the purple boxes. More details about why this matters is provided in Hexagonal Architecture – Why it works.

SUT will always be the blue boxes. Test Doubles will always (well almost always) be the purple boxes.

Test Double Types

There are several types of Test Doubles. Structurally they are all the same. Their distinction is based upon the amount of emulated behavior they provide. Test Double type names haven’t become standardized. You may see the same term used in different ways. For example, Mock is a term often used for Test Double in general, especially with Mockito, but it has a more restrictive meaning within the overall Test Double family.

Here is how I view them. Each Test Double type tends to be an extension of the one before it. When defining Test Doubles, I recommend starting with the least functional Test Double and then extending it as needed.

I’ll use a Customer Service feature in my Test Double examples. Customer Service will have dependencies upon the following interfaces:

interface CustomerRepo {

Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId);

}

interface Authorization {

boolean isAuthorized(User user);

}

Let’s assume that the SUT CustomerService only allows authorized Users to access customer information. Its API is:

class CustomerService {

public CustomerService(CustomerRepo customerRepo, Authorization authorization) {…}

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId, User user) throws UnauthorizedException {…}

}

We want to design tests that confirm authorization without knowing the implementation of CustomerService. We only know that it has two dependencies: CustomerRepo and Authorization.

We also don’t know how CustomerRepo and Authorization are implemented. The production implementations of these interfaces are probably substantial. At a minimum they would include persistence. In my test examples below, I’ll provide Test Doubles for CustomerRepo and Authorization, which won’t have any substance or persistence.

Null or Dummy

Sometimes you don’t need anything. Even if the SUT contains dependencies, you may not need to provide Test Doubles. The flow of execution through the SUT may not reference those dependencies, so there’s no need for a Test Double.

A Dummy is an implementation that mostly provides default implementations or an implementation that throws a NotImplementedException. Default implementations given the following return types could be:

- boolean returns false

- String returns “” or null

- int returns 0

- float returns 0.0

- any class returns null

- etc.

In the example below:

CustomerRepois null since it should not be accessed.Authorizationis a dummy returning false.

@Test

public void getCustomer_ThrowsUnauthorizedException_WhenUserIsNotAuthorized() throws Exception {

// Given

Authorization auth = new Authorization() {

@Override

public boolean isAuthorized(User user) {

return false;

}

};

CustomerService customerService = new CustomerService(null, auth);

try {

// When

Customer customer = customerService.getCustomer(new CustomerId("123"), null);

fail("Expecting thrown UnauthorizedException");

} catch (UnauthorizedException e) {

// Then passes

}

}

Stub

The Authorization Dummy above was sufficient for that scenario, but that was more accidental than intentional.

A Stub is one step up from a Dummy. Stub implementation is usually minimal, but it tends to be intentional.

Let’s consider a test that uses Stubs. CustomerRepo and Authorization have stubbed method implementations.

@Test

public void getCustomer_ReturnsCustomer_WhenUserIsAuthorized() throws Exception {

// Given

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

CustomerRepo repo = new CustomerRepo() {

@Override

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

return persistedCustomer;

}

};

Authorization auth = new Authorization() {

@Override

public boolean isAuthorized(User user) {

return true;

}

};

CustomerService customerService = new CustomerService(repo, auth);

// When

Customer foundCustomer = customerService.getCustomer(new CustomerId("123"), null);

// Then

assertEquals(persistedCustomer, foundCustomer);

}

Mock

The Stubbed test above is a good start, but how good is it? From the two tests, we can assume that isAuthorized(User user) has been called, but we have confirmation that the user making the request has been authorized? It passed even when the User is null. That feels a bit sketchy. Additionally, we don’t even know if the correct customerId is being used to get the Customer.

A Mock adds assertions into the Test Double to confirm invariants. Let’s upgrade the CustomerRepo Stub to a Mock to confirm customerId and the Authorize Stub to a Mock to confirm the User.

@Test

public void getCustomer_ReturnsCustomer_WhenConfirmedUserIsAuthorized() throws Exception {

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

User requestingUser = new User();

CustomerRepo repo = new CustomerRepo() {

@Override

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

if (!"123".equals(customerId.getId())) {

fail(String.format("customerId Mismatch! expectedId=123, actualId=%s", customerId.getId()));

}

return persistedCustomer;

}

};

Authorization auth = new Authorization() {

@Override

public boolean isAuthorized(User user) {

if (user != requestingUser) {

fail(String.format("User Mismatch! expectedUser=%s, actualUser=%s", requestingUser.toString(), user.toString()));

}

return true;

}

};

CustomerService customerService = new CustomerService(repo, auth);

// When

Customer foundCustomer = customerService.getCustomer(new CustomerId("123"), requestingUser);

// Then

assertEquals(persistedCustomer, foundCustomer);

}

Spy

The Mock above provides more confidence, but do we really know for sure that isAuthorized(User user) has been called for the User? The Mocked version of the test only confirms that if isAuthorized(User user) is called that it will return true for the specific User. We can infer to some degree from the Null/Dummy test above that it was called, but I don’t think it’s definitive enough.

A Spy Test Double can help with this. A Spy Test Double records its interactions and returns them via a query. Let’s make this test more obvious by upgrading the Test Double to a Spy:

class AuthorizationSpy implements Authorization {

private User requestingUser;

private List<String> actions = new LinkedList<>();

public AuthorizationSpy(User requestingUser) {

this.requestingUser = requestingUser;

}

@Override

public boolean isAuthorized(User user) {

actions.add(String.format("isAuthorized with user=%s", user.toString()));

if (user != requestingUser) {

fail(String.format("User Mismatch! expectedUser=%s, actualUser=%s", requestingUser.toString(), user.toString()));

}

return true;

}

public List<String> getActions() {

return actions;

}

}

@Test

public void getCustomer_ReturnsCustomer_WhenConfirmedUserIsAuthorized() throws Exception {

// Given

User requestingUser = new User() {

@Override

public String toString() {

return "requestedUser";

}

};

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

CustomerRepo repo = new CustomerRepo() {

@Override

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

if (!"123".equals(customerId.getId())) {

fail(String.format("customerId Mismatch! expectedId=123, actualId=%s", customerId.getId()));

}

return persistedCustomer;

}

};

AuthorizationSpy authSpy = new AuthorizationSpy(requestingUser);

CustomerService customerService = new CustomerService(repo, authSpy);

// When

Customer foundCustomer = customerService.getCustomer(new CustomerId("123"), requestingUser);

// Then

assertEquals(persistedCustomer, foundCustomer);

assertEquals("[isAuthorized with user=requestedUser]", authSpy.getActions().toString());

}

There’s more going on with the Spy. I can’t just use an anonymous class as I did with the previous Test Doubles, since the Spy has behavior not defined in Authorization. Therefore, I implemented a named class, AuthorizationSpy implementing Authorization, so that it has a public method from which to acquire the actions recording interactions with it.

For complete confirmation, we should have another test where isAuthorized(User user) returns false in a Spy to confirm that an UnauthorizedException will be thrown. Since this is getting long, I won’t provide the code. It would be a variation on the previous example.

Fake

A Fake is a Test Double on steroids. Fakes tend to emulate full behavior, but in a manner that won’t work in production. For example, there are Database Fakes that only store data in memory. They provide the complete set of DB behaviors, but as soon as the test is done, the DB Fake fades away.

Since Fakes implement so much behavior, I don’t think they are used often unless it’s a package obtained externally. I doubt that most developers are implementing their own Fakes.

How Do We Know That Emulated Test Double Behavior Is Accurate?

How do we know that the emulated Test Double behavior accurately represents the dependency’s behavior? A test is only as reliable as the emulated behavior provided by a Test Double.

This feels like a legitimate concern, but I’m going to argue that within the realm of unit testing, it’s not that much of a concern.

The dependency’s behavior should be well a defined contract defined via its interface or public methods. Test Doubles emulating dependency behavior defined via clear and well-defined contracts should not be a major challenge. However, if dependency contracts aren’t clear or well defined, then we have some options:

- Contact the dependency provider for clarification

- Create tests that interact with the dependencies to observe and confirm their behaviors, which we can then emulate in the Test Doubles.

Test Doubles emulate dependency behavior based upon the dependency’s contract. Unit tests confirm SUT functionality and its interactions with its contract defined dependencies via Test Doubles emulating those contracts. The unit test does not confirm that the dependencies honor their own contracts. Dependency confirmation is the responsibility of the dependency provider.

It took me a long time to realize this and appreciate the distinction. Before I understood contracts and their implied boundaries, I thought tests could only confirm the whole software rather than using these contracts and boundaries to separate software components so they could be confirmed separately. Sometimes dependency contracts are vague. The dependency provider may have one thought in mind, whereas the dependency user may have a different interpretation of the contract.

Unit testing won’t catch these contract interpretation inconsistencies. This is where integration testing becomes important. Consumer-Driven Contract Testing may help as well.

Test Double Inclusion

The SUT should be unaware of its dependency reference origins so that the SUT functions in production exactly in the same way that it functions in its unit test. Dependency Injection is probably the most common technique, but it only works when the SUT is loosely coupled with its dependencies.

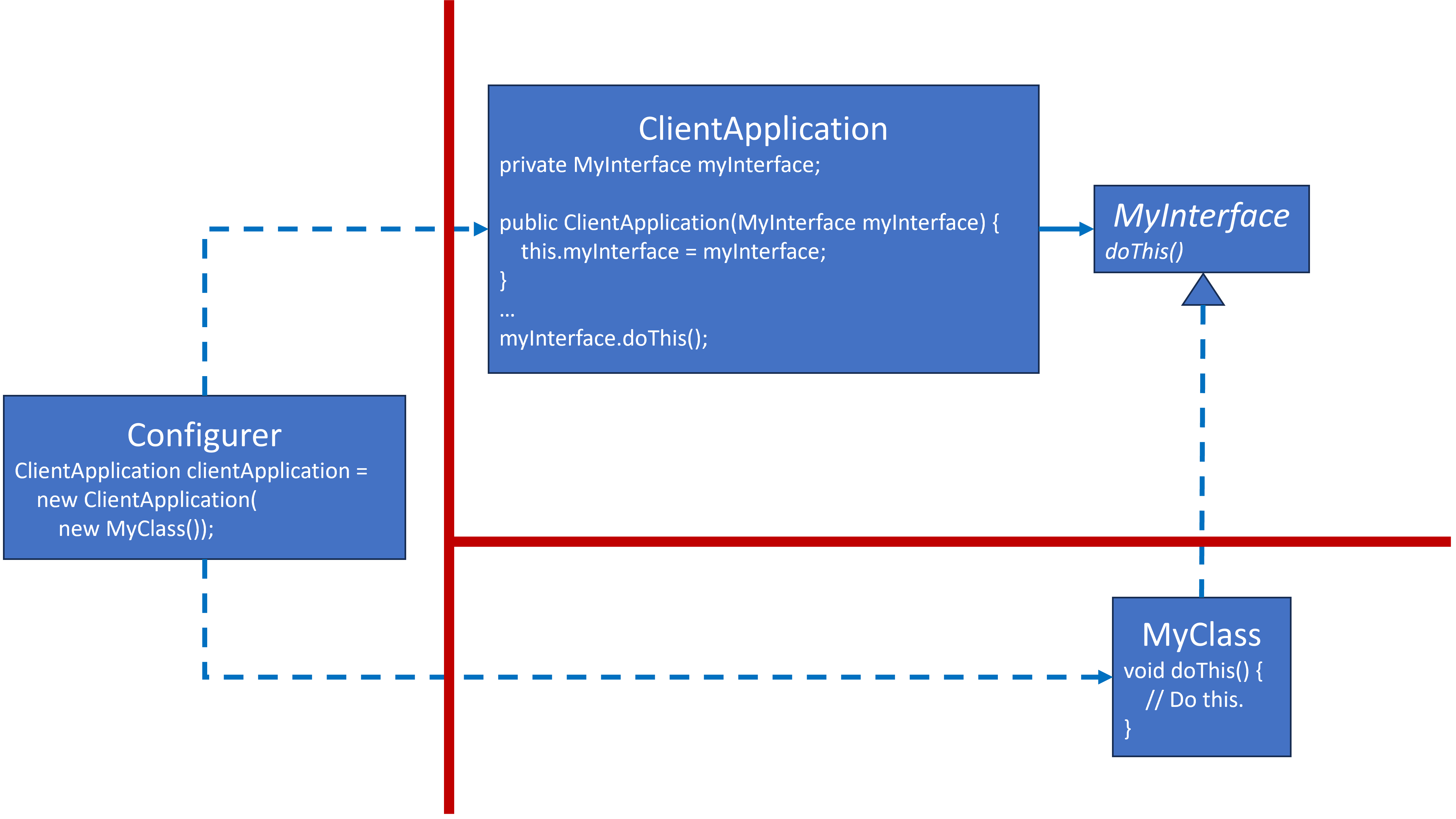

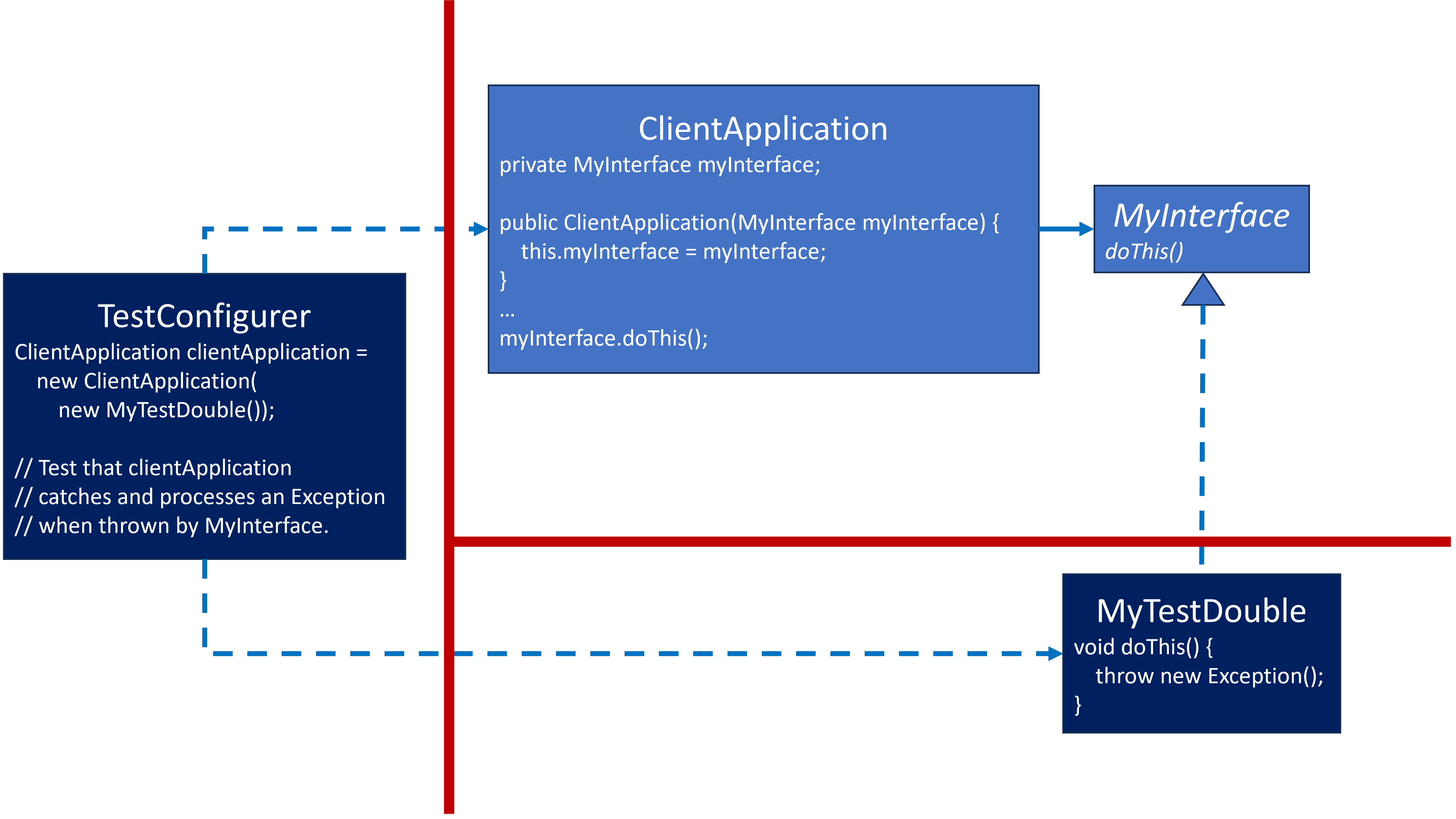

Here are two examples from the Dependency Injection blog.

Injecting a production dependency, MyClass:

The following is the same SUT, but injecting a Test Double, MyTestDouble:

ClientApplication and MyInterface are the SUT. They are unaware of any dependency specifics beyond the red boundary for which all arrows of knowledge and dependency cross that boundary by pointing toward the SUT and never away from it.

NOTE: When an SUT is not loosely coupled with its dependencies, then the SUT may need to be refactored so that it will be loosely coupled to its dependencies before Test Doubles can be added.

Constructor Injection

Constructor Injection is probably the most common technique. I’ve used this technique in my examples above with Test Doubles being injected into the CustomerService via a constructor.

Configurers manage this. A Production Configurer will inject production dependencies. A Test Configurer, usually the test as well, will inject Test Doubles.

We can have both Production and Test Configurers since no other elements in the design tends to depend upon them. In design diagrams, arrows point away from them, not into them. They are invisible to the rest of the design. They are invisible to each other.

Therefore, we can drop the SUT in many different test and production scenarios without the SUT having knowledge or dependency upon those scenarios.

Method Injection

Method Injection is much like Constructor Injection, except that the dependency is injected via a method, which is similar to, but not the constructor. Some classes may have a set accessor which allows dependencies to be updated after object construction.

Dependency Frameworks

Some frameworks, such as the Spring Framework, provide mechanisms, such as the @Autowired annotation, but they are mostly wrappers to facilitate dependency injection.

Method Override

Sometimes the dependency is within the SUT class itself, which can happen when the SUT is tightly coupled to its dependencies, which is common with Legacy Code.

I will feature Method Override in the next blog, but I will briefly describe it here:

- Method Override works to decouple tight dependencies in the SUT.

- The dependency may be external, such as a direct call to a DB API. The dependency may be another class in the project. Or the dependency may be code within the method being tested.

- Separate the dependency into its own method using the Extract Method refactoring. Most IDEs provide a tool to do most of this for you. The extracted method will probably be declared as

privateby default. We will need to remove this so that it’s package-private. This will keep the method hidden from elements outside the package, but it will be accessible to elements inside the package, specifically the test code. NOTE: This is Java terminology. Other languages may have different terminology. - When creating the SUT class in the test, override the extracted method and inject the Test Double behavior needed for the test.

Method Override leaks implementation details into the tests, which makes them a bit more brittle. I use Method Override sparingly, but sometimes it’s the best technique until the SUT can be refactored more so that the dependencies are truly loosely coupled.

Write Your Own Test Doubles Or Use A Framework?

My examples in this blog have been handwritten Test Doubles. They aren’t huge, but each one takes at least five or six lines as seen in this Stub:

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

CustomerRepo repo = new CustomerRepo() {

@Override

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

return persistedCustomer;

}

};

Maybe I could have saved a few lines via a lambda rather than an anonymous class, but that would only work for functional interfaces with one method. Most interfaces have several methods. What if the CustomerRepo were:

interface CustomerRepo {

void createCustomer(CustomerId customerId, Customer customer);

Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId);

void updateCustomer(CustomerId customerId, Customer customer);

void deleteCustomer(CustomerId customerId);

}

The anonymous class above would not work unless it included implementations for the other three methods in the interface, even if they were not referenced by the SUT in the test. Then much like the AuthorizationSpy, we’d need a CustomerRepoDummy:

class CustomerRepoDummy implements CustomerRepo {

public void createCustomer(CustomerId customerId, Customer customer) {

throws new NotImplementedException();

}

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

throws new NotImplementedException();

}

public void updateCustomer(CustomerId customerId, Customer customer) {

throws new NotImplementedException();

}

public void deleteCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

throws new NotImplementedException();

}

}

Then in the test, we can do this:

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

CustomerRepo repo = new CustomerRepoDummy() {

@Override

public Customer getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) {

return persistedCustomer;

}

};

Writing your own Test Doubles is not your only option. There are Test Double frameworks, such as Mockito.

I created my own Test Doubles as I was learning how to implement unit tests. This gave me the freedom and power to define Test Doubles that did exactly what I wanted them to do. It also helped me distinguish SUT from Test Doubles, which can be a bit confusing when first learning how to implement unit tests. It also provided an environment where I truly learned what I could and could not do with Test Doubles rather than copying some Test Double framework specification I found online, didn’t understand, but hoped it did what I wanted it to do. However, there was a tradeoff to creating my own Test Doubles. They were larger and took more time to implement.

As I gained more confidence, I started to dip my toe into the Mockito waters. I was able to create and inject Test Double behavior more quickly. A Mockito version of the previous Test Double might be something like this:

Customer persistedCustomer = new Customer();

CustomerRepo repo = mock(CustomerRepo.class);

when(repo.getCustomer(any(CustomerId.class)).thenReturn(persistedCustomer);

Mockito is more concise. Its mock creates a Dummy and the when/thenReturn pairing allows us to inject Stub behavior for getCustomer only.

I migrated to Mockito for my Test Doubles. Mockito was faster to specify in most cases. For the most part I liked Mockito, but it had some quirks. Mockito Test Double defined behavior can be a bit cryptic. Its specifications are inconsistent. For example the syntax for stubbing behavior is completely different in these three cases:

// For a typical Test Double

when(repo.getCustomer(any(CustomerId.class)).thenReturn(persistedCustomer);

// For when repo is the SUT ... I think. I was never quite sure.

doReturn(persistedCustomer).when(repo).getCustomer(any(CustomerId.class));

// For when CustomerRepo.getCustomer(CustomerId customerId) is a static method.

// It was a hassle, but at least it allowed me to create Test Doubles for static methods.

try (MockedStatic<CustomerRepo> customerRepo = Mockito.mockStatic(CustomerRepo.class)) {

customerRepo.when(CustomerRepo.getCustomer(CustomerId.class)).thenReturn(persistecCustomer);

// Complete testing that references static within the try-with-resources block.

}

When you make a specification mistake, which you can see from above is easy to do, it often won’t alert you. It just won’t work as you think it should. I spent a lot of time scratching my head staring at my SUT implementation to find the problem when the real problem was in the Mockito Test Double specification.

There were times when I just couldn’t emulate the Test Double behavior that I wanted. This could have been behavior that Mockito did not support, or it could have been Mockito knowledge that I didn’t quite have yet. I’d create my own Test Double when I couldn’t continue with Mockito.

While this is completely subjective, I recommend the same path. Create your own Test Doubles until you gain confidence and understanding of Test Doubles. Then slowly migrate to a Test Double Framework, such as Mockito.

Summary

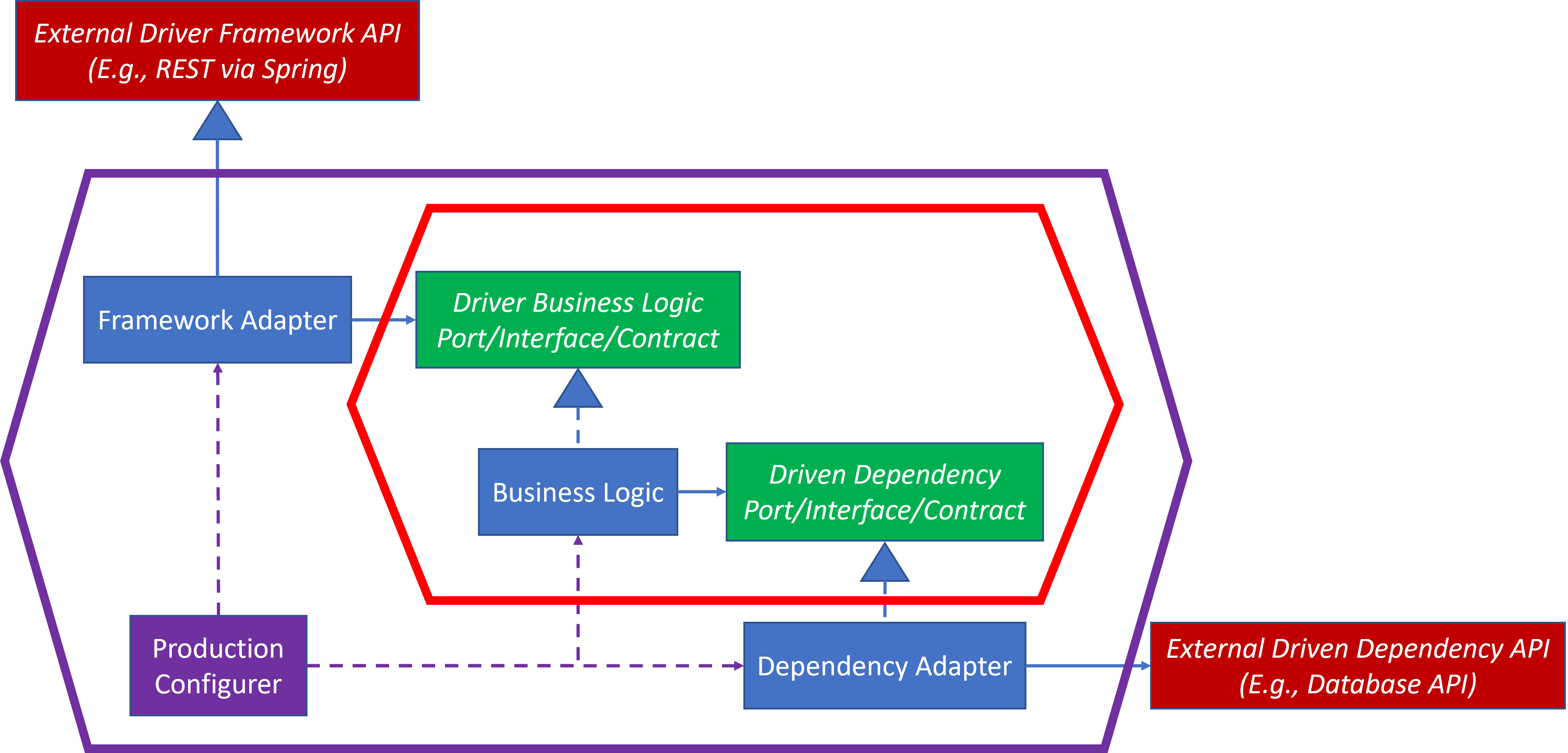

Test Doubles has been the focus of this blog, but there’s something more subtle afoot. Many ideas from previous blogs are coalescing into a common theme and Test Doubles has been a catalyst for that reaction.

Here’s a brief review of some previous ideas with blog references that are coalescing:

- Program to an interface, not an implementation from Design Pattern Principles. This principle is crucial for loose coupling.

- Strategy Design Pattern, and to lesser degree Adapter and Façade as well, to design for loose coupling.

- Dependency Injection with Configurer to resolve dependencies.

- Hexagonal Architecture – Structure especially hexagonally shaped boundaries to highlight contracts and boundaries:

- Dependency and Knowledge Management, which was presented in the context of Hexagonal Architecture, which also applies beyond the Hexagonal Architecture design, to allow SUTs to be unaware of their execution environments.

Future blogs will introduce additional concepts that will coalesce as well. I feel there may be a grand unified theory of software engineering that’s still just a bit beyond my grasp. If there is such a grand unified theory, I’d be willing to bet that Dependency and Knowledge Management is part of it.

References

- Previous blog references

- Test Doubles on Wikipedia

- Test Doubles by Martin Fowler

- Test Doubles on xUnit Patterns

- Test Doubles on Test Sigma Blog

- Test Doubles in Android

- Test Doubles Chapter 13 from Software Engineering at Google by Andrew Trenk and Dillon Bly

- Test Doubles from MSDN Magazine from Microsoft

- Mockito on Wikipedia

- Mockito on Mockito.org

- Mockito on GitHub

- Mockito Guide on DZone

- Mockito RefCard on DZone

- Mockito Tutorial on Baeldung

- Mokito’s Mock Methods on Baeldung

- Mocking Static Methods With Mockito on Baeldung

- Clean Unit Tests with Mockito on Refactoring.io