What Is Behavior in BDD Exactly?

Oops. I didn’t define "Behavior" in the Behavior-Driven Development blog.

Introduction

I received feedback from a reader the day after I published Be On Your Best Behavior, which featured Behavior-Driven Development (BDD). The reader asked:

One question on this [BDD] article. Practically, what is a behavior? Is it that:

- User gets registered, or

- Clicking register button triggers register method

- Or would these both need to be catered for at different levels of testing?

My apologies to the reader and anyone else who didn’t know what I meant by behavior. I’ll try to address that here.

What Is Behavior

I didn’t define behavior in the BDD blog, since I’m not sure I can easily define it. It’s sort of like art. I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it.

I’ve stated the intertwined relationship of behavior and implementation before: Behavior emerges from the implementation, and implementation is shaped by the behavior.

Implementation is bit processing. The computer will execute any code. There is no intrinsic behavior in the code. Behavior is the context that humans apply as they observe the execution of the implementation.

With BDD we specify desired behavior before the code has been implemented. That is, through BDD, we specify the desired behavior so that we can best shape the implementation from which that observable behavior will emerge.

Desired behaviors have been presented to most software developers in different forms throughout their careers via:

- Programming assignments in academia

- Interview whiteboard questions

- Requirements documents

- Enumerated requirements

- Use Case descriptions

- User Stories and Acceptance Criteria

- Conversations with Domain Experts

The above examples tend to describe behavior using natural language. With BDD, we specify behavior and codify it within a test, which becomes a living dynamic specification that is reconfirmed with each test execution.

I’ve also used the term Observable Behavior, which for me is behavior defined in the contract. Observable behavior defines what the software does without indicating how it does it.

A padlock and key provide an example of observable behavior without providing any indication of the internal mechanism within the padlock and its key:

- Given a Key that matches the Lock, When the Key is inserted into the Lock and turned, Then the Lock opens.

- Given a Key that does not match the Lock, When the Key is inserted into the Lock and turned, Then the Lock does not open.

Register User or Click Register Button

The reader asked if behavior applied to:

- User gets registered, or

- Clicking register button triggers register method

- Or would they need to be catered at different testing levels?

My first thought was that the first bullet, Register User, was the type of behavior I was considering when writing the BDD blog entry. But before I could complete my response to him, I realized that behavior could include button clicks and even different testing levels.

Caveat: I’m about to dip my toe into behaviors that tend to be associated with product behaviors as defined by Domain Experts via User Stories and Acceptance Criteria. Behavior can also be scoped to individual classes and methods, in which case, they would be specified in the unit tests and probably wouldn’t have User Stories or Acceptance Criteria. As I stated in the Behavior-Driven Development blog:

The major distinction I make between unit or integration/acceptance testing is the scope and boundary of the SUT. Unit tests tend to have smaller scoped SUTs. Integration/Acceptance tests tend to have larger scoped SUTs. Regardless of the SUT scope, we still want tests that confirm the behaviors bounded by the scope of the SUTs.

User Stories

Let’s flesh out these behaviors with a bit more detail.

Register User

As a User, I want to register myself, so that I have an identity in the system.

This isn’t a blog about User Stories, but it demonstrates how useful they can be. This is a mediocre user story at best. There’s no context. An actual product will have context, but the context might only reside in the heads of the domain experts. The context may not be obvious to the developers.

Side Bar:

I worked on a product with a geographically distributed team spread across the country. My domain expert’s location was several time zones from mine. This was before Slack, Teams, online video and other remote communication platforms were common. We only had email and phones, so we weren’t as closely connected with remote coworkers as is possible with today’s technology.

Our team met once a year in a common location for product coordination, team building, etc. I was chatting with my domain expert about relatively recent requirements he had written. He casually stated something about the feature. I interrupted him and said, “That sounds like a requirement. I don’t remember reading that in the requirement document.” He replied, “It’s an unwritten requirement.” I responded, “In the future, I’d prefer for the unwritten requirements to be written too.”

I don’t view a user story as a requirement. I view the user story as providing context and a prompt for conversation between domain experts and developers. The conversation is probably going to be developers asking questions of domain experts for more context and clarity, such as:

- Are there different types of registration?

- What information is associated with a registered user?

- What happens if the user is already registered?

- Is user authentication and authorization required?

- Can a user unregister? This question may reveal a missing scenario. This should be addressed in another user story.

- Can a user update his/her registration information? This should be addressed in another user story as well.

Since this is a hypothetical situation, I can’t answer these questions. However, in an actual product with domain experts, these questions can be resolved or lead to even more questions and discussions.

These conversations should distill into Acceptance Criteria (AC), which specify observable behaviors in the Given-When-Then structure. ACs may generate more questions as well.

User Stories and ACs create an environment in which to think about and reveal the true nature of the product behavior. Considering these hypothetical scenarios is like running tests in the mind. In a pure environment, we would flesh out User Stories and ACs before any architecture, design or implementation decisions have prejudiced anyone’s thoughts about the product.

Beware of injecting architecture, design or implementation into User Stories or ACs. It’s not uncommon for User Stories and ACs to dictate how the product is built rather than specify what it does.

A user story with many ACs may be an indication of a user story that’s trying to convey too much user intent. It may be an indication that the user story is too broad and needs to be split into more granular and narrowly focused user stories. The split threshold is more of a matter of personal feeling than a specific number of ACs. It also depends upon the nature of the ACs. If the ACs cluster into cohesive groups, then each cluster may indicate its own user story.

The user story and ACs provide the context and behavior of user registration. The user story defines the context of user desire. The ACs specify behavior. The user story provides the context in which to better understand the ACs. It should be obvious how Given-When-Then ACs can be transformed into Given-When-Then tests. Given-When-Then Acceptance Tests are basically ACs in the form of coded tests.

Here are several candidate ACs for the Register User use case, which are missing the contextual details that would have been included had this been associated with an existing product.

AC: Register New User Indicates Success

- Given an unregistered User,

- When that unregistered User registers,

- Then the User is registered in the system. Status is indicated via a USER_REGISTERED response.

AC: Register Existing User Indicates Duplicate User Registration

- Given a registered User,

- When that registered User registers,

- Then There is no attempt to register the User in the system. Status is indicated via a USER_REGISTRATION_DUPLICATION response.

Click Register Button

Is clicking a Register User Button a User Story? Only in the context of UI/UX design. User Stories define Customer/User intent and desire. That is, they define the Users’ wish to register themselves. Users probably don’t have a great urge to click a button, unless it’s the History Eraser Button. Clicking the button is a mechanism to trigger registration, which in all fairness to the reader is exactly what he described in his second behavior bullet example.

There may be other form factors that users can use to register themselves, such as a Mobile App or a digital assistant, as in Alexa. User intent shouldn’t depend upon these registration mechanisms.

I mention this because not everyone shares this opinion about User Stories and Acceptance Criteria. I’ve worked in some organizations that have created user stories and ACs like the example below.

As a User, I want to click on the Register User Button, so I can register myself in the system.

AC: Register User

- Given the system is up and running,

- When a User clicks on the Register User Button,

- Then the User is registered in the system.

These organizations are performing Agile methodology practices without understanding their purpose. User stories and ACs like my example above create useless overhead so that a box can be checked giving the illusion of progress. Don’t follow a process blindly. Process should work for us. We shouldn’t work for the process.

Even if I don’t consider Click User Register Button a use case, code is required to implement the UI/UX. This code should be tested too.

Testing Design

Let’s see how the progression of tests defines behavior and leads toward a design. Since this is a hypothetical case, there are still unknowns especially with external dependencies. In some cases, we don’t care. But in others we will eventually care.

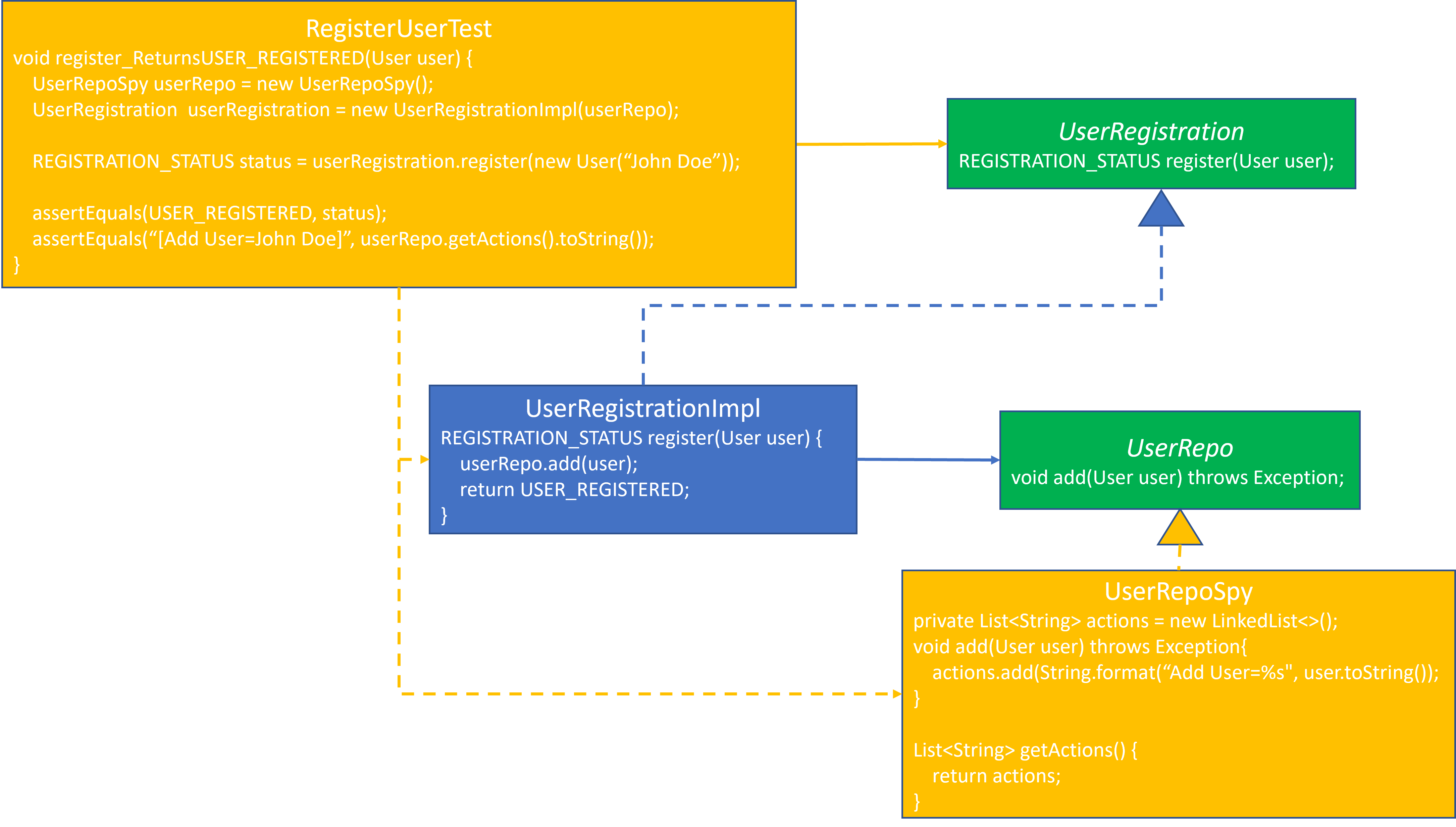

Rectangle Color Coding Key:

- Green - Contracts, which would be interfaces in Java

- Blue - Production class implementations

- Yellow - Test drivers and Test Doubles

- Red - External dependencies

Register User

Registering a user is the core behavior. This first test specifies the return status and an interaction with the UserRepo contract, which can be tested and implemented even if we don’t know how the UserRepo will be implemented.

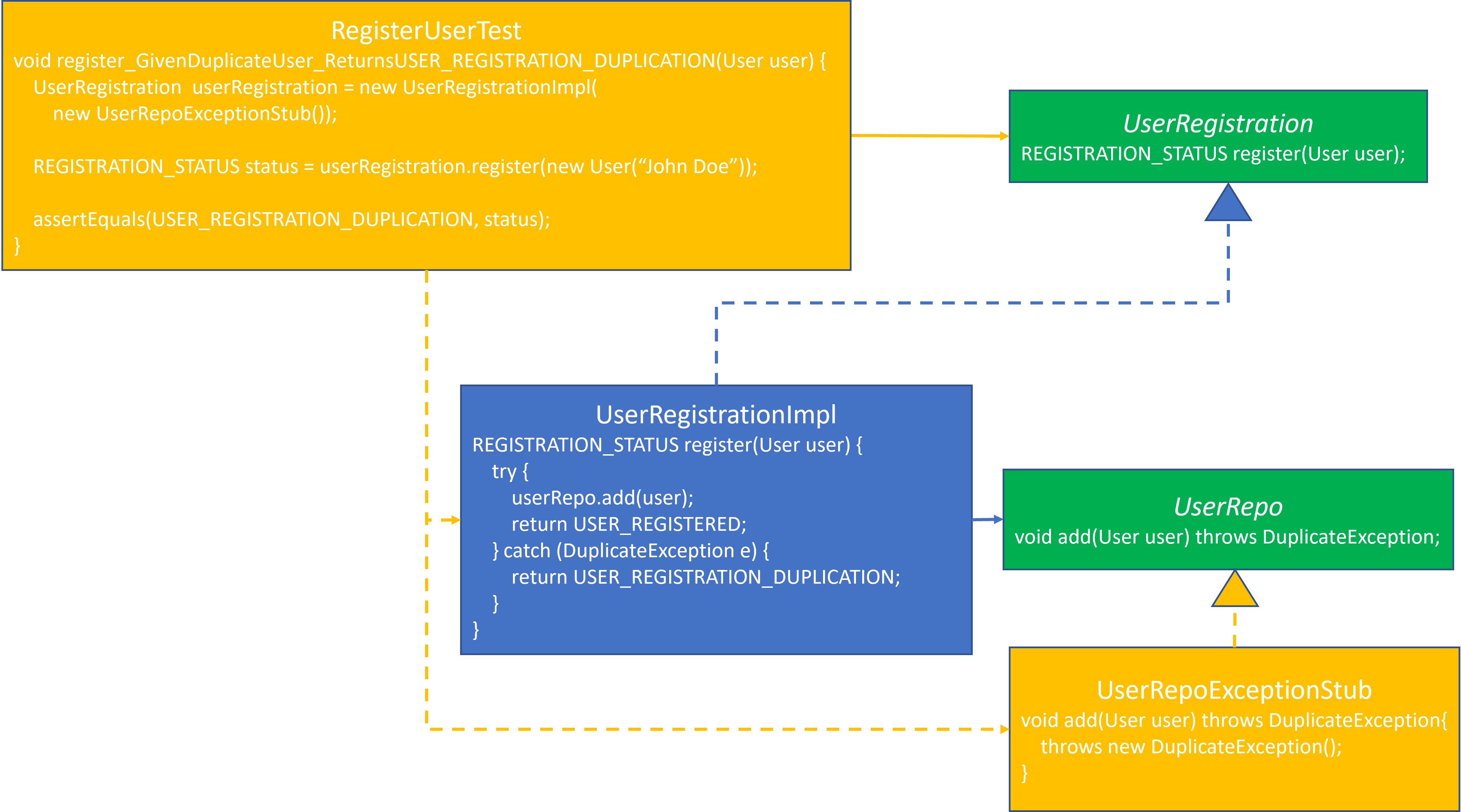

This next test design expands upon the previous test with an exception case.

What is the purpose of UserRegistationImpl? There’s not much substance, since this is a hypothetical case. However, it still feels like we’re missing behavior:

- Should the User be validated?

- What if registration is for a subscription service, and the User’s payment is not up to date?

Don’t add these additional behaviors into UserRegistrationImpl until you have confirmed them with the domain experts or the PMs. If they confirm this behavior, then document it via Given-When-Then ACs and specification tests.

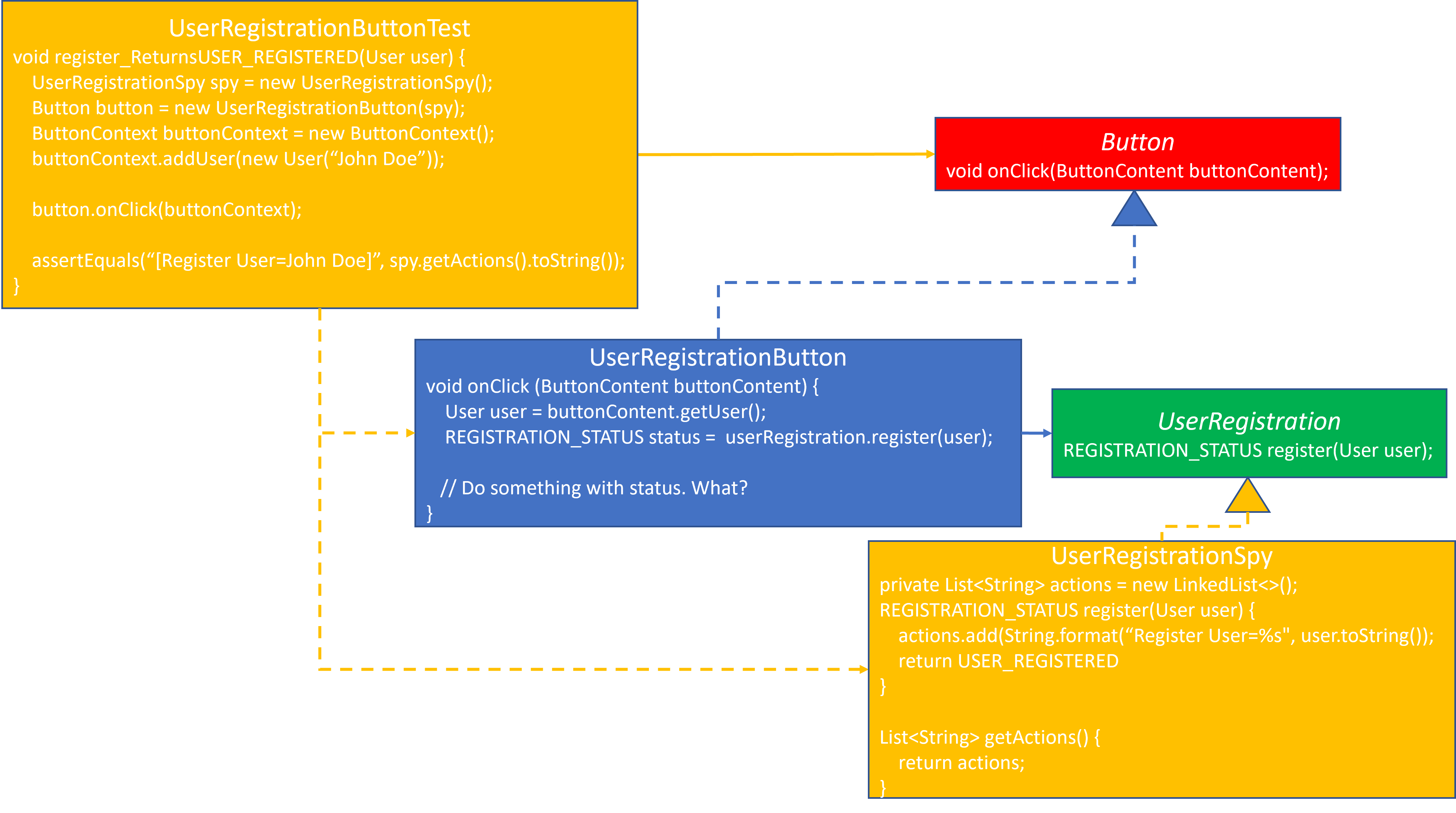

Click Register Button

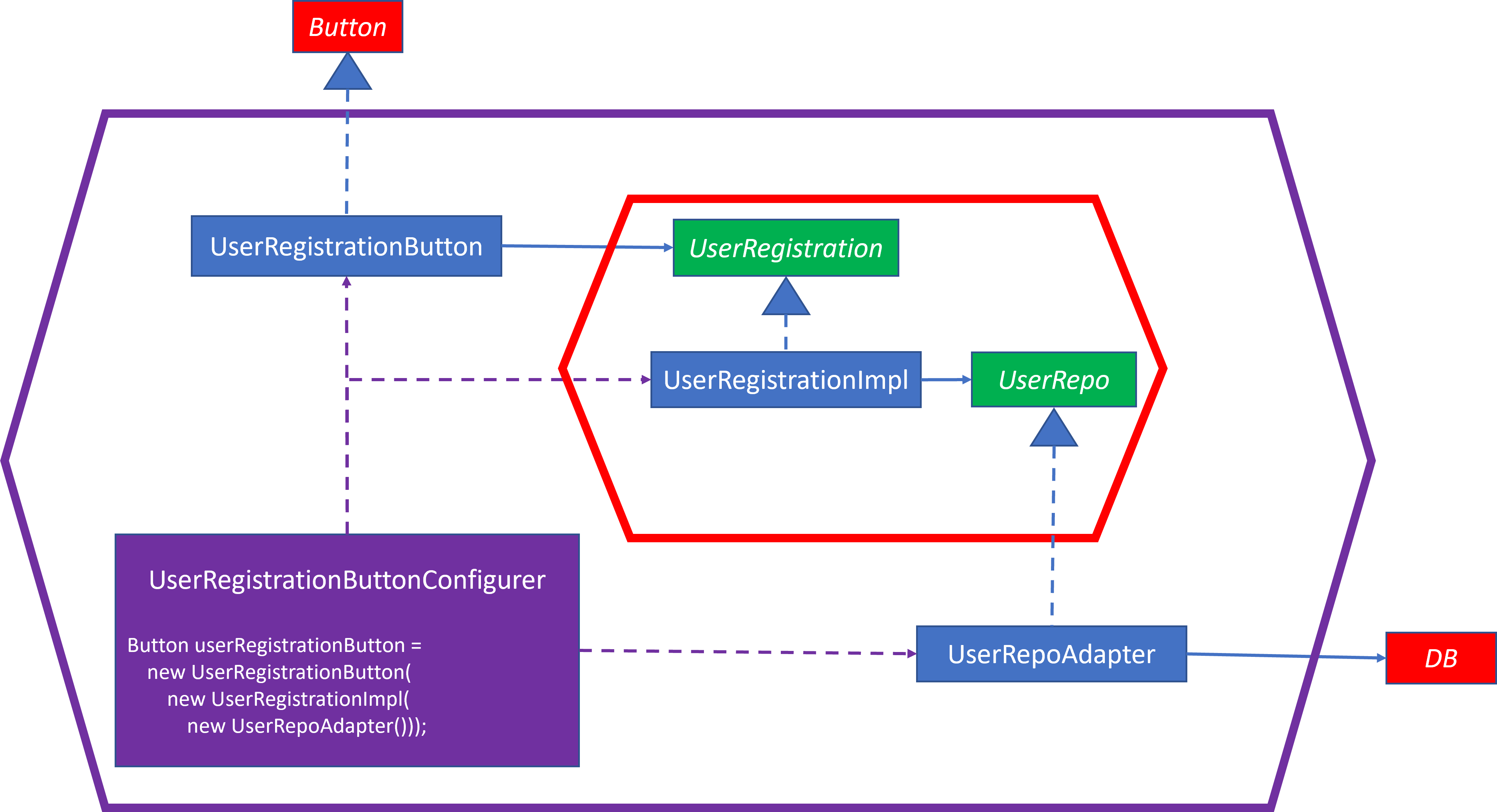

Let’s move toward a registration button. I’ve colored Button red, since it’s an external dependency that we don’t control. It’s part of a GUI framework.

This test isn’t so much about functional behavior as it is about UI/UX behavior. UserRegistrationButton is an Adapter. It implements Button by delegating to UserRegistration. This User Registration behavior happens at the press of a Button without UserRegistration knowing about or depending upon the Button. The design also supports additional Adapters if needed for a Mobile App or Alexa without any updates required for UserRegistration. Each would require an Adapter, such as UserRegistrationViaMobileAppAdapter or UserRegistrationViaAlexaAdapter.

This is where unknowns arise. I’m not sure what to do with the returned REGISTRATION_STATUS. This would be a conversation I’d have with the UI/UX designers. They are the domain experts when it comes to user experience, and they would need to describe how the user would experience a successful registration and a duplicate registration attempt. The user’s experience related to REGISTRATION_STATUS would be different for a Web App button, Mobile App button and Alexa. The Adapters for each would manage these differences.

This test won’t confirm the look-and-feel of the button. It only confirms what happens when the button is clicked. Look-and-feel confirmation tends to require human confirmation. UI tests have traditionally been difficult and brittle, but new UI test frameworks are on the market, which may support UI testing.

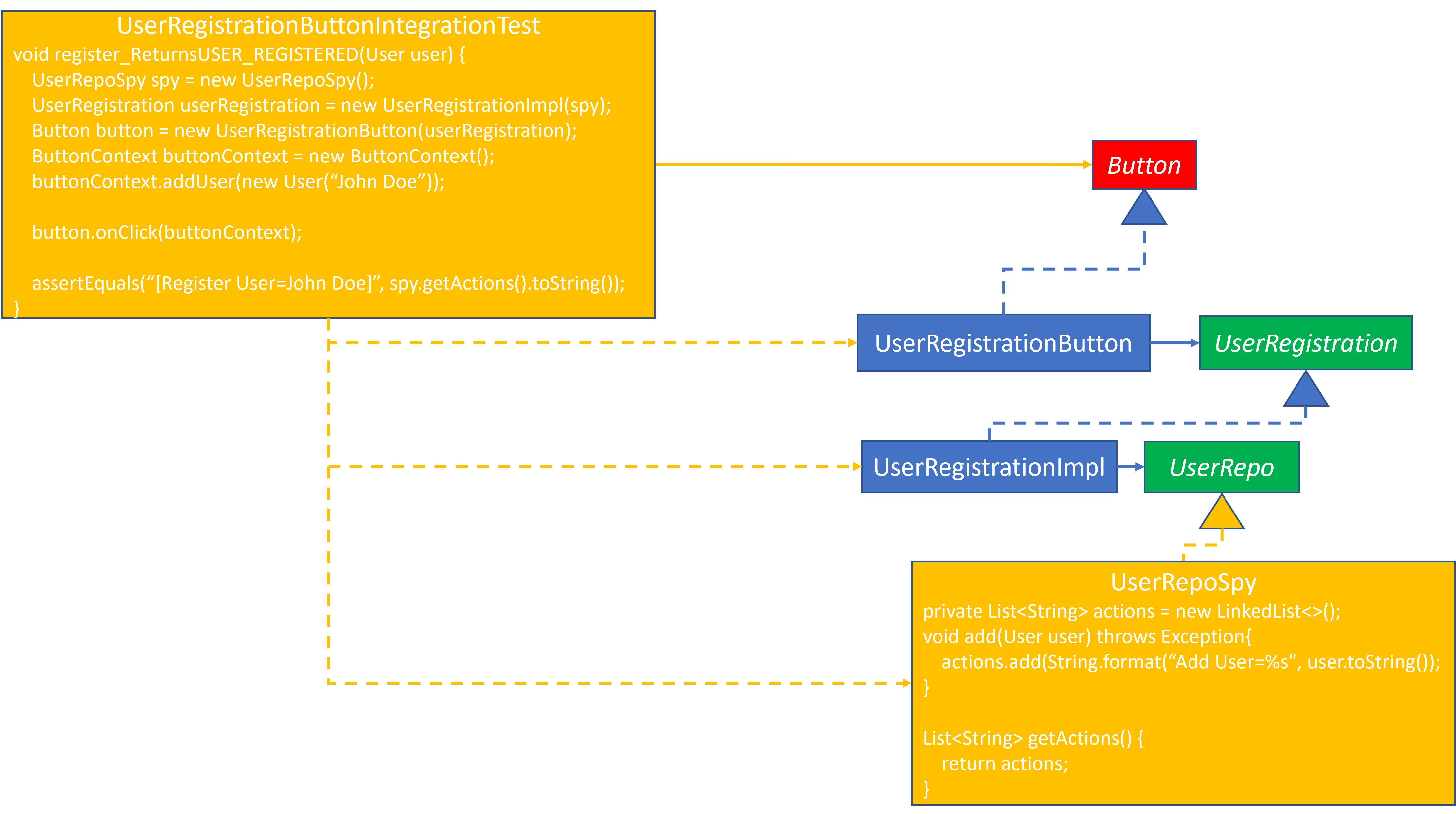

Integration Testing

Let’s integrate these tests. I’ve removed the implementation details due to space considerations. The implementations are the same as above.

The test confirms that when the UserRegistrationButton is clicked that there’s an attempt to register the User in the UserRepo. And I still haven’t defined UserRepo.

End to End Testing and Production

Once we get to end-to-end testing and production, which are the same except for the context in which they are executed, we need a UserRepo implementation. In this example, I’ve created a UserRepoAdapter, which delegates to an external DB.

I still don’t know any DB details. This is an architectural decision that’s been isolated from the rest of the design, so it can be delayed. The DB could be Mongo, MS-SQL or even a flat file. The dependency details would be managed in UserRepoAdapter, which is a generic Adapter name, since I haven’t chosen a DB technology. Each potential DB technology would have its own dedicated Adapter, such as UserRepoMongoAdapter, UserRepoMsSQLAdapter or UserRepoFlatFileAdapter. For example, we might initially deploy with a UserRepoFlatFileAdapter and as the product matured, and we wished to move to a production DB, then we’d swap out the previous Adapter with UserRepoMongoAdapter.

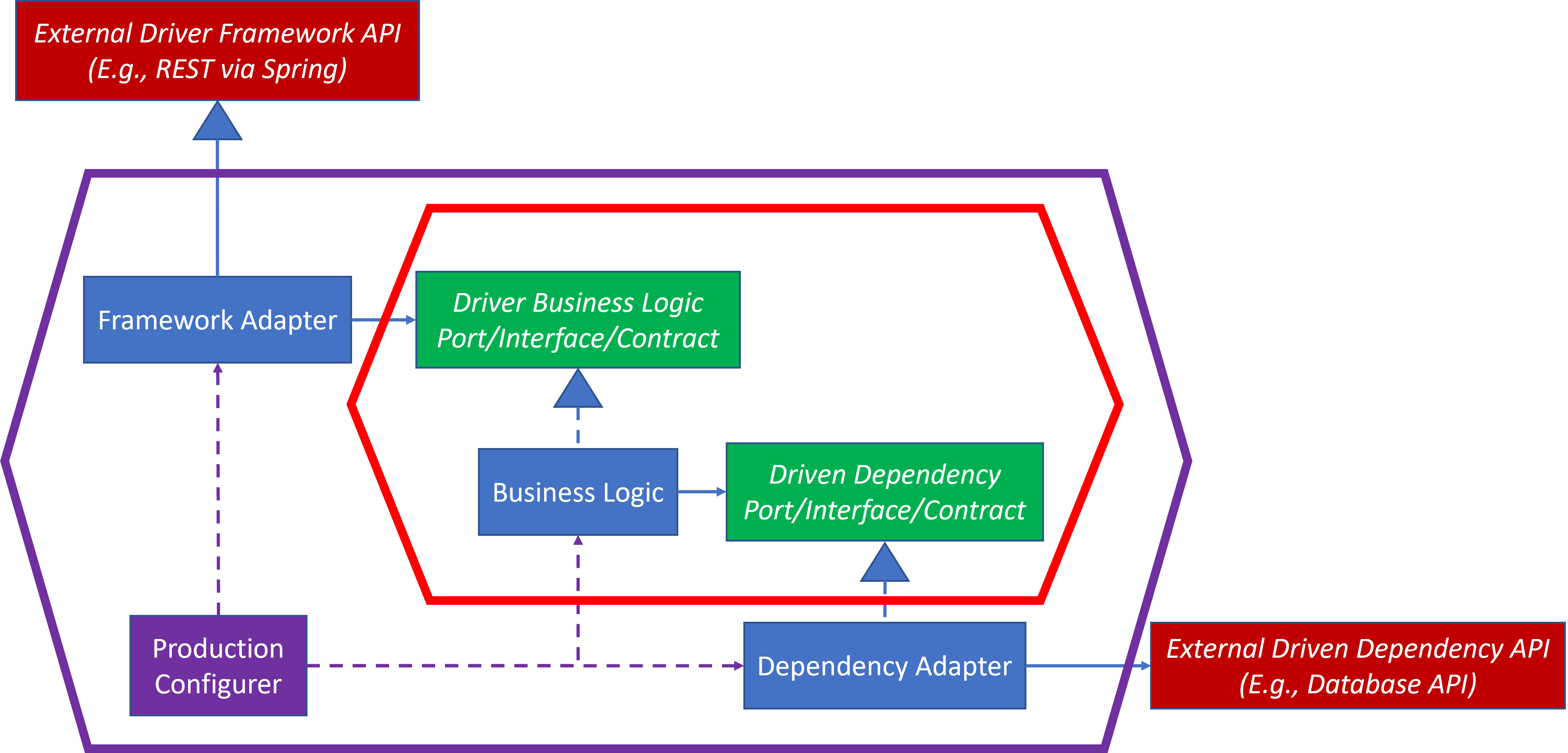

I’ve also rearranged the elements and added more notation to show that, SURPRISE!, the design is an example of Hexagonal Architecture.

Take a look at Hexagonal Architecture Structure and notice that most of what I’ve described for User Registration is a specific example of what I described generically almost a year ago.

The only difference between the image above and the one below is User Registration specifics above and generalities below.

Summary

Behavior is context applied to the execution of code as observed by people. This took us on a journey of working through User Stories into Acceptance Criteria, Tests and eventually a Hexagonal Design.

This blog was inspired by a reader asking me a follow up question. I encourage feedback. My contact information is at the bottom of my About Page. Contact me, and I’ll try to repond either directly and/or via updating the blog or a new blog entry.

References

- Previous blog references