Hexagonal Architecture – The Structure

Why it’s also called Ports and Adapters

Introduction

This continues the Hexagonal Architecture series with the structure of Hexagonal Architectures.

Chess Is More Than the Pieces

As I mentioned in It’s Your Move, I started to learn the foundations of chess in The Logical Approach to Chess by Euwe, et al. In the same way that this book opened my eyes to how to play chess, the Design Patterns opened my eyes to how to create better Object-Oriented designs.

The first lesson in the chess book isn’t about the pieces. It’s about the chessboard. Specifically, it’s about the importance of the center squares of a chessboard. Controlling those squares gives you more options than if your opponent controls them.

The Developer Chessboard

Is there a developer chessboard? Sort of, but it’s not quite the same. The empty developer chessboard is mostly a blank slate. It doesn’t have any predefined features at the start. The landscape doesn’t take shape until we start to put things in it. Maybe Carcassonne is a more apropos game, so let’s roll with that for a bit.

Carcassonne is a tile playing game, an example of which can be seen in the image at the top of the page. The game space is empty until tiles are played, and the tile edges must align based upon geographic features at the edges of the tiles.

Much like Carcassonne, software design starts with a blank slate. Software design game space takes shape as we place our tiles, in the form of software elements. Much like the tiles of the game, software elements must align if they interact.

The game space of software design consists of two types of tiles:

- Your code

- All the other crap

Your Code

By your code, I’m referring to the code that tends to have your name on it when git blame is activated for a file. This code will also tend to be where the project’s Business Logic resides regardless of a specific developer ownership. It will also include some infrastructure plumbing that allows your code to interact with the other crap. Your code is often someone else’s crap too.

All the Other Crap

The other crap are the other parts of the system and their dependencies. Some of these will be internal components provided by developers on other teams, your team, or possibly even you. Some will be external components purchased from vendors, acquired via open source or part of the system’s platform. Here are some examples of external components:

- Database Products

- File Systems

- The Web

- Messaging Platform

- Frameworks

- Open-Source Libraries

- Configuration Information

- System Clock

These external components are External Dependencies from the point of view of your code.

There is a distinction between external dependencies. They come in two flavors.

The first is more obvious. These are dependencies that your code delegates to. Calls to these dependencies is DRIVEN by Business Logic. For example, the Business Logic code may delegate to the Database, Open-Source Library, File System and Clock APIs. These dependencies traditionally appear on the right-hand side of Hexagonal Architecture diagrams.

The second is a bit more subtle. These are dependencies that delegate to the Business Logic code. Calls from these dependencies DRIVE the Business Logic. Frameworks are an example of this. How often do you declare main()? I’d be willing to bet that it’s probably not too often. main() often resides within the framework, and it eventually calls your code. These dependencies traditionally appear on the left-hand side of Hexagonal Architecture diagrams.

Sometimes there’s a hybrid, such as with a Messaging Platform, which resides on both the left-hand and right-hand side of Hexagonal Architecture diagrams. The Business Logic might produce events, in which case it delegates to the Messaging Platform. The Business Logic might consume events, in which case it’s called by the Messaging Platform. And it’s possible that the Business Logic could be a consumer and a producer.

How “Your Code” Interacts with These Dependencies

The Business Logic will only interact with the dependencies that it requires. This may be a fraction of the potential dependencies in the system.

The External Dependency APIs were not designed with your specific Business Logic needs in mind. External Dependency APIs tend to be more generic. Hopefully, the External Dependency API designers considered their user’s needs and designed an API to accommodate those needs as much as possible. However, I have found that External Dependency APIs tend to present what the dependency provides and not so much what the user needs. Developers need to accommodate External Dependency APIs. They figure it out, but often with the expenditure of blood, sweat and tears.

Even after figuring it all out, these External Dependency APIs may be embedded in Business Logic code. The coupling is more than just functional dependency to execute the external behavior. The Business Logic code will have knowledge of those dependencies baked into the implementation.

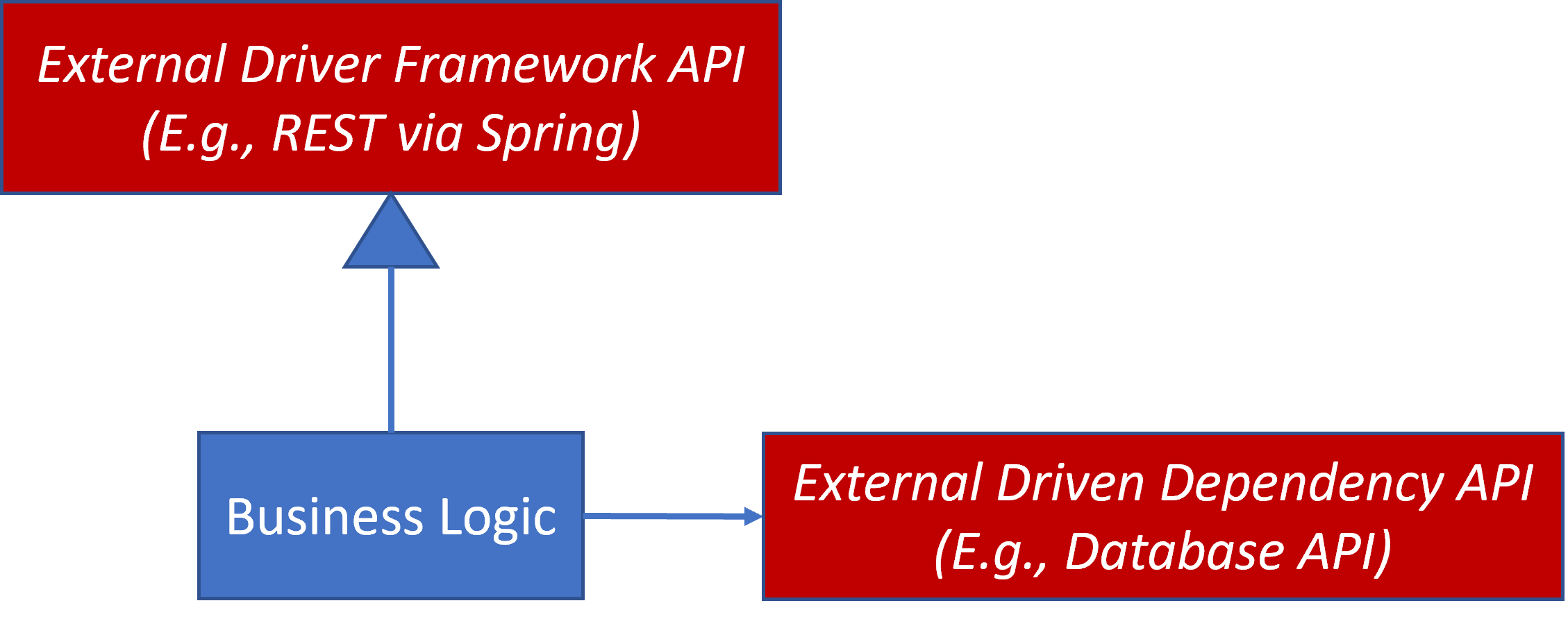

Here’s a simple example of Business Logic that implements a Framework, possibly something like REST, and delegates to an External Dependency API, possibly something like a Database. The design will work, but it’s not modular, flexible, or very maintainable. This example only highlights two External Dependencies. Most designs will have more. A back-of-the-envelop estimation can be acquired in some languages by counting the number of external references. For example, in Java count the number of import statements. I’ve worked in some classes that have had over 50 project specific import statements. That’s almost certainly a class that’s doing too much and can be refactored.

This simple design runs into problems since the Business Logic is tightly coupled to its Dependencies. I’ve colored the External Dependencies red to indicate that they’re a little dangerous, since their management resides outside of the control of the developer of the Business Logic.

I have encountered this design more times than I care to remember. I’ve seen Business Logic Controllers where everything was in one huge multi-hundred line method. The REST code, business logic, database access and other dependencies were mixed together like the ingredients in a stew. The ingredients were so intermingled, that it became difficult to distinguish which parts did what.

Ports and Adapters

When we play the game with only your Business Logic and its Dependencies, we end up with working code, but not necessarily flexible code. Can we play this game better?

I think we can. I’m going to add two new types of tiles. I’m adding what Alistair Cockburn calls Ports and Adapters. It turns out we’ve already seen these elements before. They’re concepts that align with the Essential Design Patterns.

The Port

Advice to address tight coupling resides in the first design pattern principle: Program to an interface, not an implementation.

The Port is an Interface. I’m going to introduce a third term here too, Contract. It’s not just that the Business Logic depends upon an Interface, which is mostly an implementation detail. I’m more interested in the context in which the Business Logic depends upon the Port/Interface.

A Port is a design element with Hexagonal Architecture. An Interface is an implementation detail. The methods declared within it are a Contract. A Contract declares the expectations and obligations of both the user and provider of the methods without indicating implementation details. The Contract should honor the Single Responsibility Principle and the Interface Segregation Principle by being a cohesive set of methods.

External Dependency APIs are often thrust upon us. They aren’t always a cohesive set of methods that honor the principles listed above. In this Port focused design, we have the opportunity to shake the Etch-A-Sketch.

We can design the Contracts that the Business Logic needs; not the one we’re stuck with. Being able to create customized Interfaces/Contracts for Business Logic is addressed briefly in the Façade Design Pattern Summary.

Introducing Ports

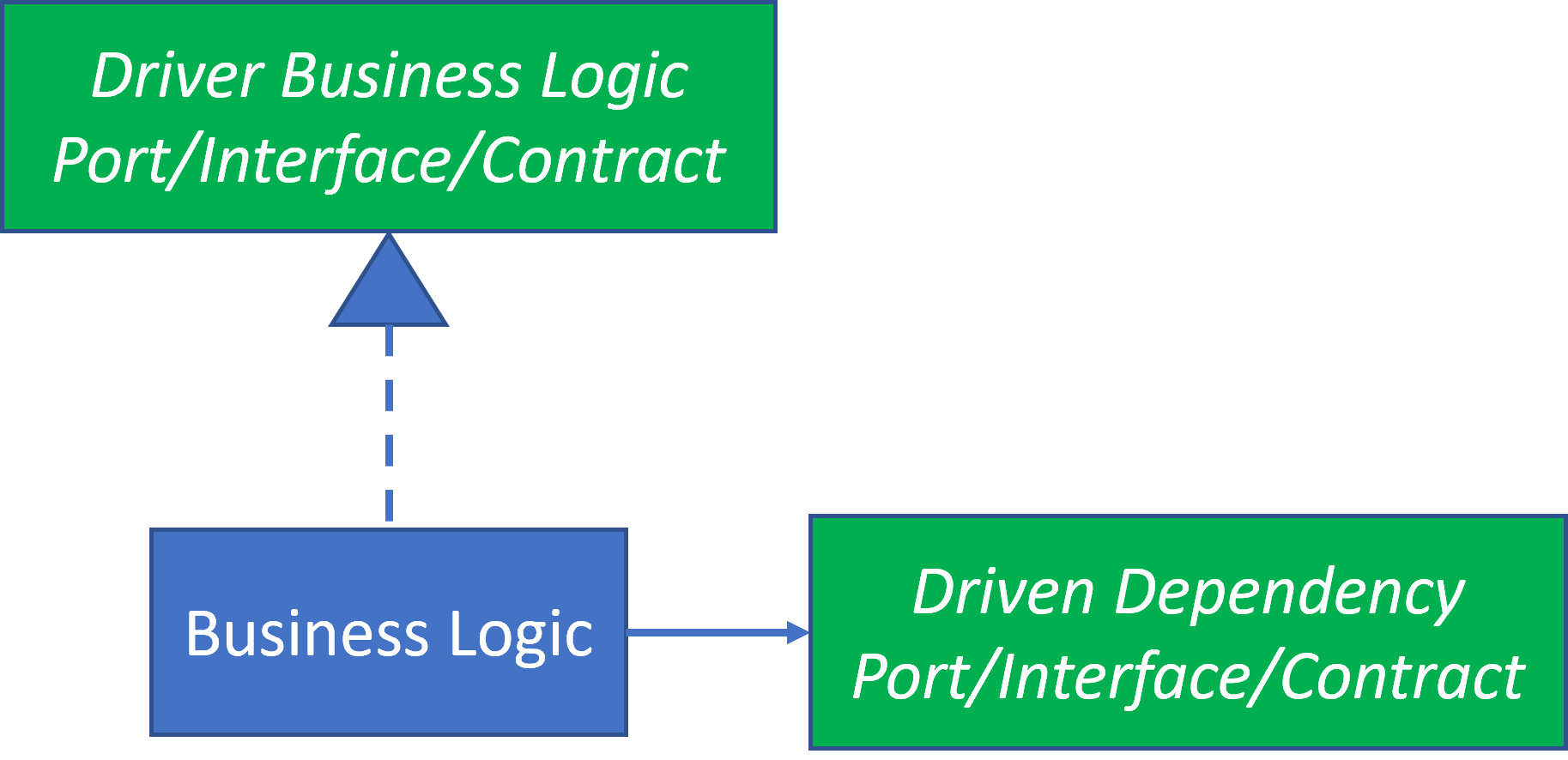

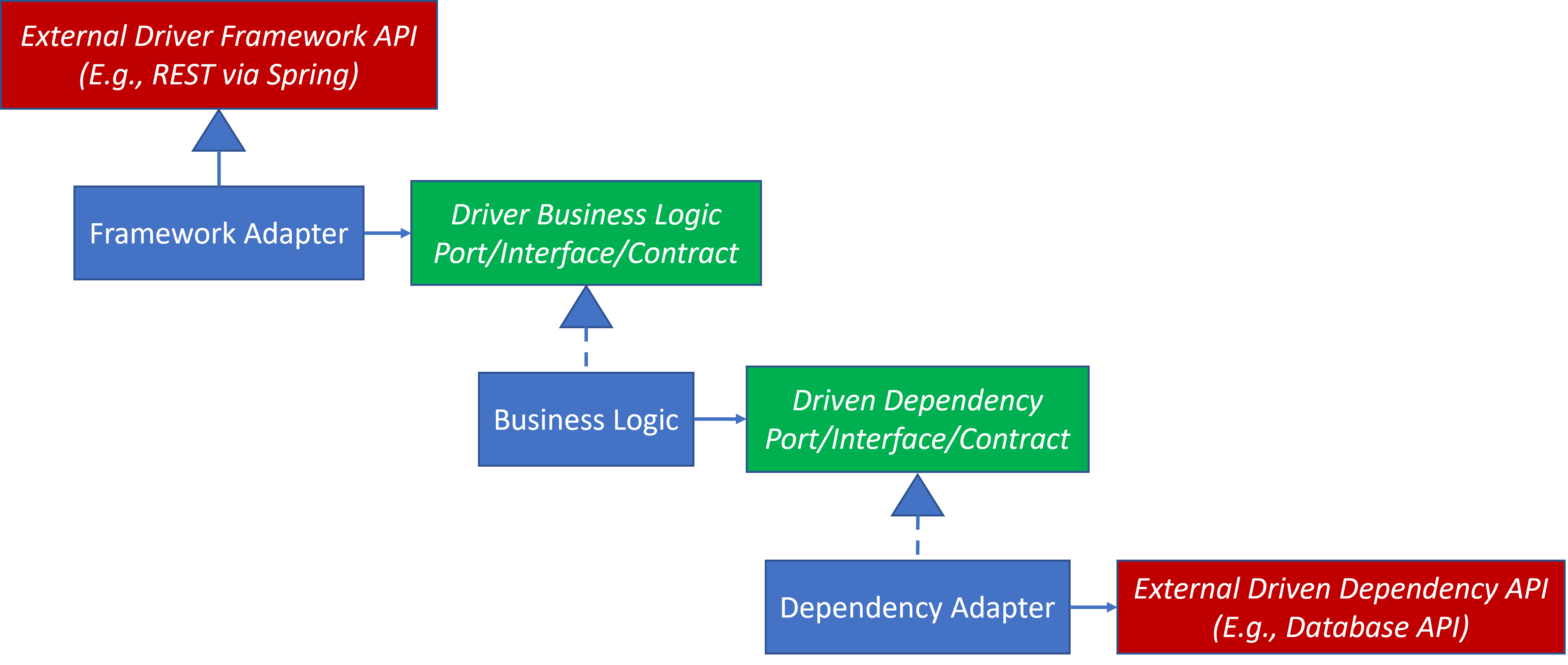

Ports are design elements often implemented as Interfaces, which declare a Contract. Here’s how the Business Logic would depend upon Ports/Interfaces/Contracts. I’ve colored them green to indicate that they’re benign, since their management resides completely within the control of the developer of the Business Logic.

The Driver Business Logic Port is an interface that declares the Contract of the Business Logic. Defining a Contract allows the developer to encapsulate the Business Logic design. I’ve represented the Business Logic as a single rectangle, which suggests a single class in UML class diagrams, but this could be a package consisting of multiple classes as well.

The Driven Dependency Port is an interface (or interfaces) that declares the Contract for the external behaviors needed by the Business Logic.

But what happened to the red External Dependencies from the previous diagram. We don’t need them … yet.

In what order do we design and implement the feature? These three elements may grow organically, but here’s one order in which the design and implementation could proceed:

- Start with the Business Logic Contract. It does not need to be complete. One method will suffice.

- Implement the Business Logic using Test-Driven Development.

- When the Business Logic implementation needs behavior that it cannot provide, then declare what it needs in a Driven Dependency Contract.

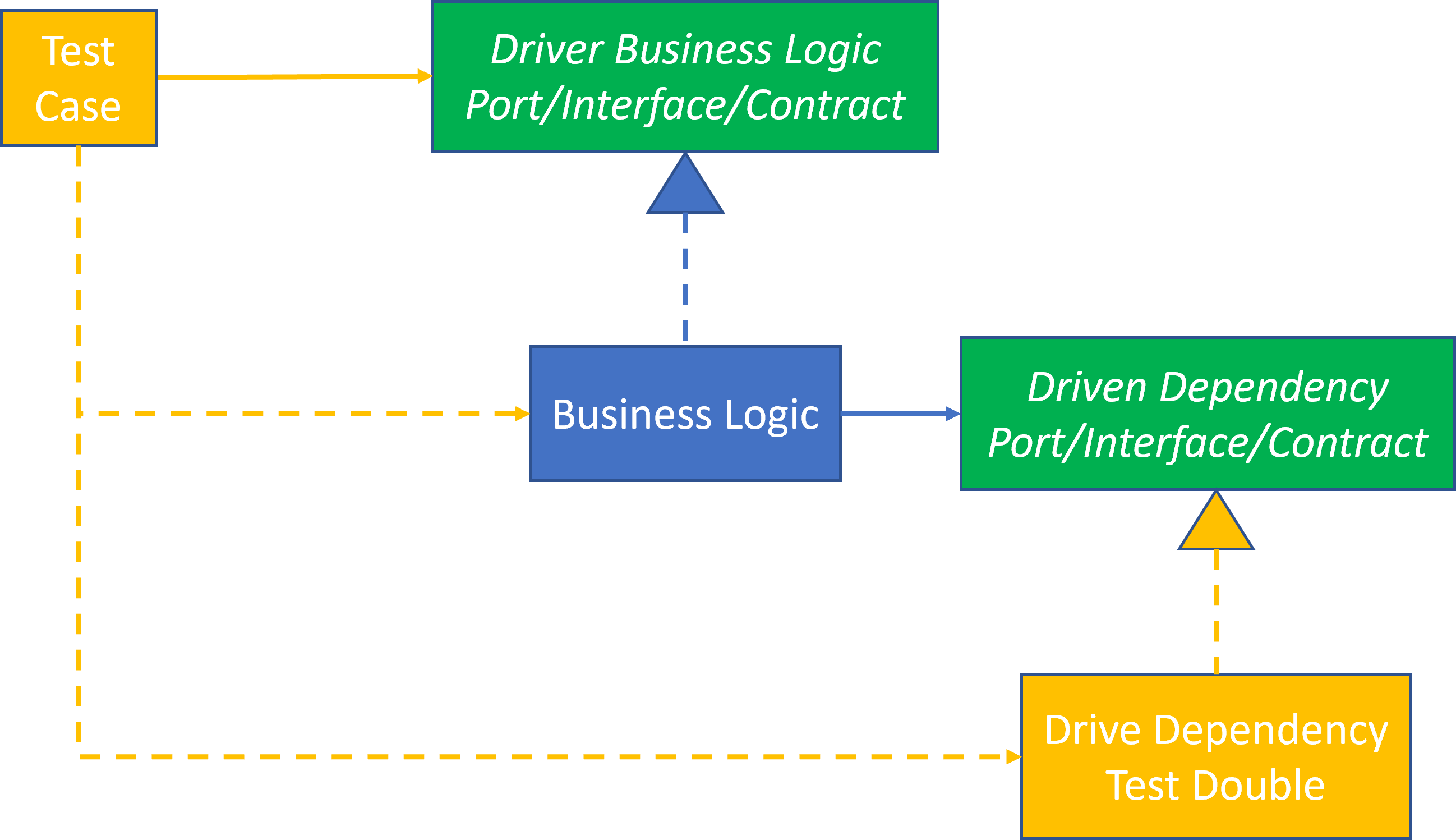

The design to do this, along with the testing, would look something like this where Test Case:

- Creates a Drive Dependency Test Double

- Injects it into a created Business Logic object

- Validates behavior via a test via the Driver Business Logic

The Adapter

The above works well, but eventually you’ll want to see the Business Logic in production. And if you’re practicing Agile, you’ll want to get into the hands of the user for feedback.

We can add the External Dependencies back into the design using Adapters.

The Framework Adapter has all the Framework details, in this example REST, but it does not contain the business logic. It delegates to the Business Logic Contract.

The Dependency Adapter implements the Dependency Contract by delegating to the External Dependency.

This design allows the Business Logic to interact with the External Frameworks and Dependencies without being tightly coupled to them.

The design doesn’t eliminate the blood, sweat and tears needed to figure out how to interact with External Dependency APIs. But this interaction is segregated in the Adapters, which may make it a little bit easier to manage, especially since it’s not intermingled with the Business Logic implementation.

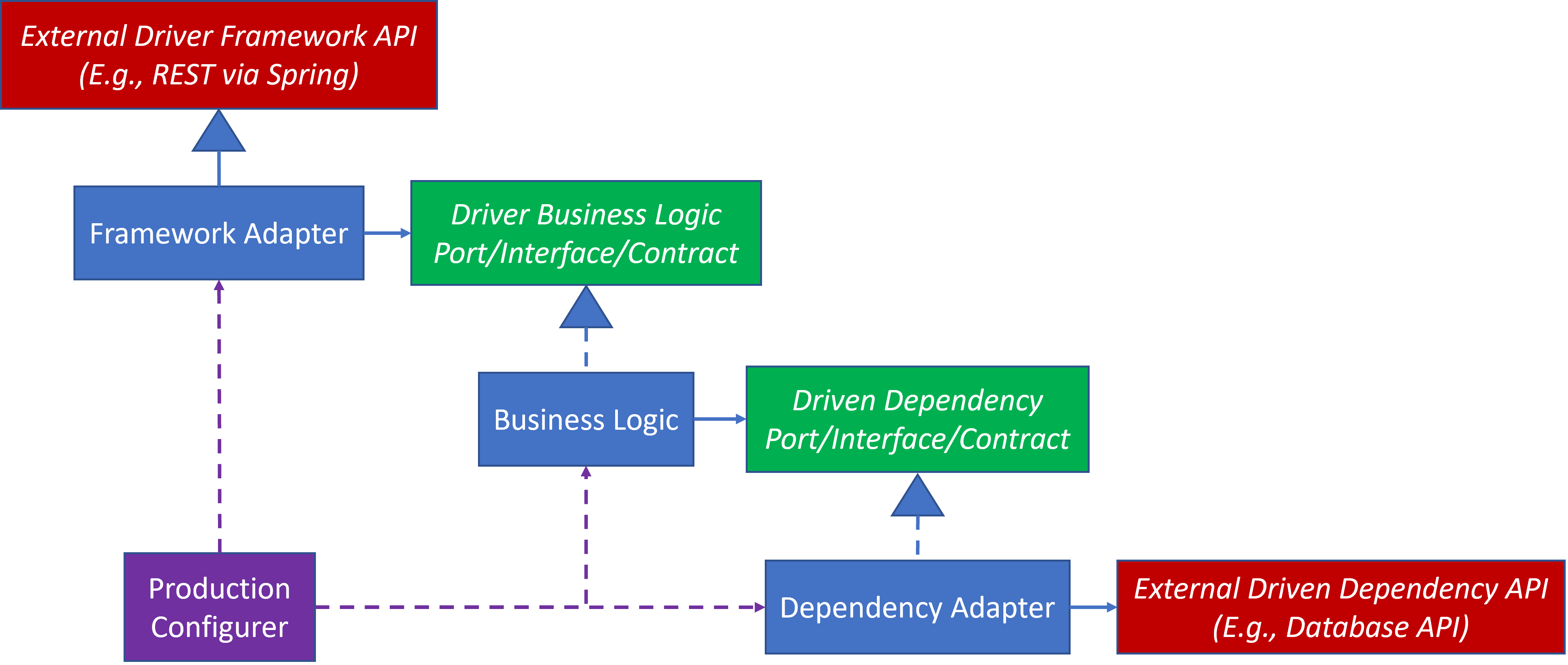

Configuration

Most depictions of Hexagonal Architecture/Ports&Adapters stop here. They don’t indicate how the blue classes are constructed. That’s where Dependency Injection fills in the final detail.

Here a design that includes object creation. The Production Configurer’s responsibility is to create and configure the objects in this design for production. It does so by:

- Creating the Dependency Adapter object

- Injecting that object into the Business Object when creating it

- Injecting the Business Object into the Framework Adapter object when creating it

And if the ProductionConfigurer’s structure looks similar to TestCode’s above, that’s because TestCode is a Configurer too. It’s a Configurer for a unit test environment.

Keep in mind that in the above, the ProductionConfigurer is the only element that has knowledge of all three concrete classes. Its implementation will tend to be fairly straight forward as something along these lines:

FrameworkAdapter frameworkAdapter =

new FrameworkAdapter(

new BusinessLogic(

new DependencyAdapter()

)

);

Additional configuration may be needed in ProductionConfigurer to ensure that frameworkAdapter is registered with the Framework.

The FrameworkAdapter has no information about the concrete DependencyAdapter. It doesn’t have knowledge of the DrivenDependencyInterfacePortContract. The FrameworkAdapter only has knowledge of a DriverBusinessLogicPortInterfaceContract. It doesn’t know its concrete class.

It’s also possible for a different BusinessLogic implementation to request a completely different set of External Dependencies. If this were the case, then the Configurer for that different implementation would need to know the appropriate External Dependency Adapters and inject them into the that specific BusinessLogic implementation, but the FrameworkAdapter would be completely independent of it. Here’s an example of an alternative configuration for a different scenario, where DifferentBusinessLogic requires three different Dependency Adapters:

FrameworkAdapter frameworkAdapter =

new FrameworkAdapter(

new DifferentBusinessLogic(

new DependencyAdapterA(),

new DependencyAdapterB(),

new DependencyAdapterC()

)

);

If there are more parts to assemble, then the configuration might be delegated to Factories at the appropriate encapsulation.

Variants

The diagrams in this blog post only include one example for each element type to keep the diagrams from becoming too cluttered.

In most real Business Logic, there will be multiple Driven Dependency Contracts and almost certainly multiple External Driven Dependencies. There may be multiple Frameworks too.

This is why Cockburn used a hexagon. Each side represented a facet with a Port on one side and Adapter on another. He envisioned as many Port/Adapter pairs as would be required.

Design Patterns

So far, this design has mentioned several design patterns: Adapters, Dependency Injection and Factories. There are potentially more in this design:

- The Ports/Interfaces/Contracts are parts of Strategy, and it’s possible, in the right circumstances, that they could be implemented using Template Method.

- Since the Ports/Interfaces/Contracts are designed for the Business Logic and not directly from the External Dependencies, a single External Dependency may not be sufficient to satisfy the Contract. It may require interaction among several External Dependencies. If that’s the case, then the design would require a Façade.

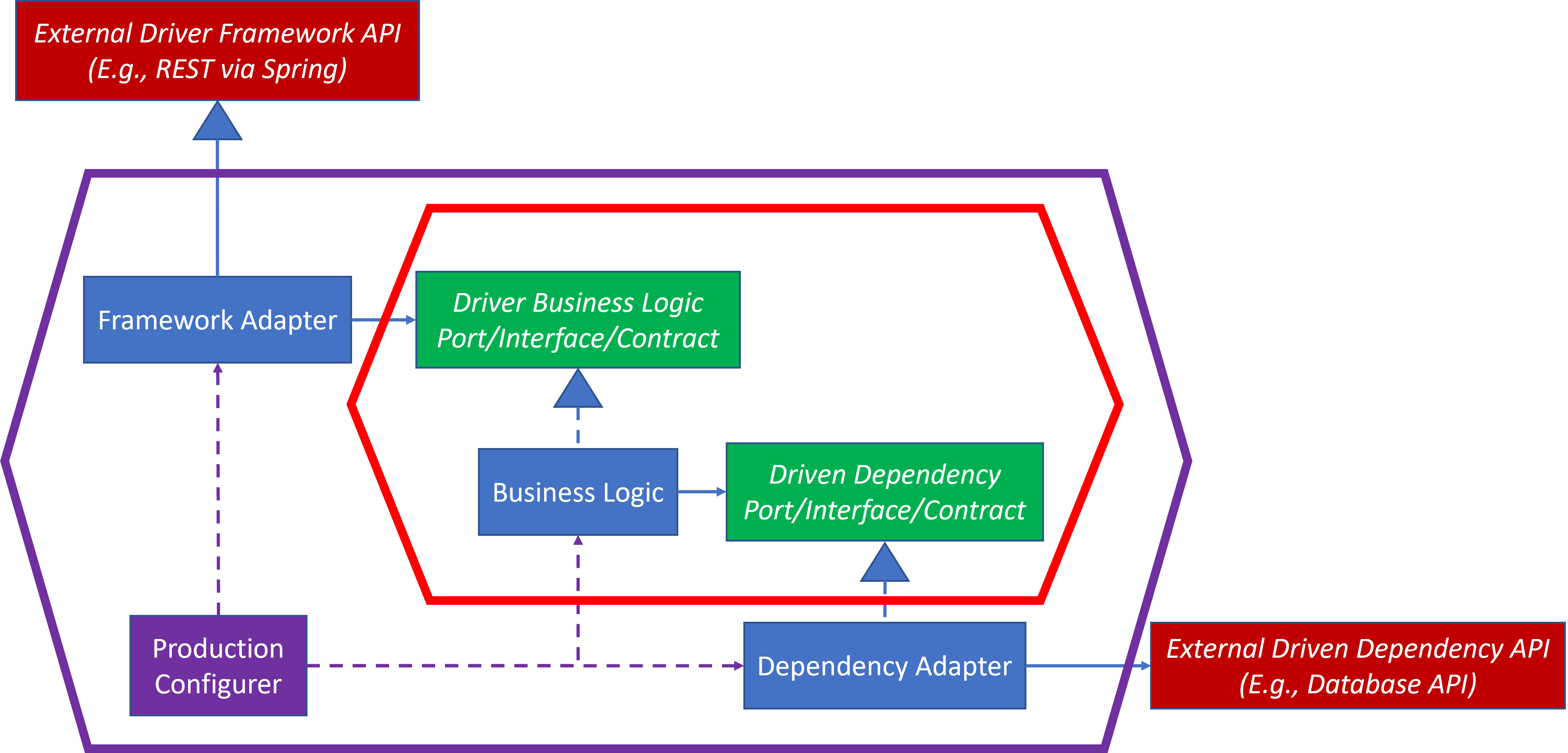

Hexagonal Architecture

I am deep into my second blog about Hexagonal Architecture, and I still haven’t shown any hexagons! I’m about to remedy that.

There is no consistent way to draw the Hexagonal Architecture. A Google image search for Hexagonal Architecture, et al. will confirm that. Everyone puts their own spin on it. I’ll be adding my own too.

This diagram is the same as the previous diagram, but with two hexagons added:

- The space inside red hexagon is reserved for Business Logic. This is the cocoon I referenced in the previous blog entry in the Pluggable Design section. The Business Logic has no dependency upon nor knowledge of anything beyond the red hexagon. The red hexagon lines are nearly identical to the red lines shown in Dependency Injection

- The space beyond the purple hexagon is where all External Dependencies reside.

- The space between the red and purple hexagons is reserved for the Adapters and Configurators that allow the Business Logic to interact with the External Dependencies without being tightly coupled to them.

Summary

That’s the basic structure of the Hexagonal Architecture/Ports & Adapters. There are several moving parts, but it’s not too difficult to grasp given a little time to study it.

The design’s main purpose is to insulate Business Logic from its External Dependencies. The Contracts allow the Business Logic to focus upon what it needs to do and not how it will do it. The Adapters/Façades will translate most of the how.

There are other implications of this design, which I’ll address in future blogs posts in this series. We’ve already seen one of the implications – the Business Logic testing is almost trivial to set up.

In the next blog post, I’ll present why I think this design works so well.

References

See previous blog References.