Object Pool Design Pattern

An exploration of how Object Pools improve performance by reusing costly-to-create objects

Introduction

High-throughput systems demand not just speed but predictability. Creating and destroying heavyweight objects under load introduces latency spikes, memory pressure, and unpredictable jitter. Object Pools smooth out these rough edges by keeping expensive resources warm and ready.

The Gang of Four (GoF) omitted Object Pool as a design pattern from their catalog. It may have been omitted because the pattern had not yet matured or become widely adopted at the time of their publication.

Even if the GoF had included it in their catalog, they may not have considered it a Creational Design Pattern, since an object is not created when acquired. However, I still consider it a creational pattern, since from the client’s point of view, the object is being acquired, even if the specific acquisition mechanism, which is often object creation, is encapsulated from the client.

Intent

Object Pool allows multiple clients to access a set resource-intensive objects without having to instantiate them for each use. Resource-intensive objects may be expensive to instantiate, such as requiring a lot of time, or they are coupled to a limited resource, such as a hardware constraint.

For example, opening a new database connection requires authentication, network I/O, driver negotiation, and often server-side session creation. Creating one for every request would overwhelm the database and the application.

An Object Pool is allocated with a number of resource-intensive objects often at start up. Then when a client requests one, the client acquires a resource-intensive object from the pool and then returns it when done with it so that it’s available for another client.

There are many real world examples of shared Resource Pools including:

- Secretarial Pools - Though mostly a thing of the past, executives would acquire a secretary from the pool, who could take dictation, type a letter, do filing or perform other secretarial skills. Once done with a task, secretaries would return to the pool for the next executive’s task. Secretarial pools are not as prevalent today, but they were common before the advent of office computers. Women in the secretarial pool were sometimes featured on the TV Show set in the 1950s or 1960s such as Mad Men.

- Video Rental Stores - Though mostly a thing of the past as well, video rental stores often had multiple copies of a title, especially for the latest hot releases. A video rental is akin to a Flyweight/Object-Pool hybrid model of customer-requested titles with multiple physical copies for each title.

- Bowling Ball Shoe Rentals - Customers rent a pair of shoes while at the bowling lanes and then return them when done.

Here are a few examples more aligned with software:

Object Pool Design and Implementation

I will layer in various Object Pool design and implementation considerations.

Flyweight vs Object Pool

Object Pool is structurally similar to Flyweight, but there are some differences. Developers often confuse Flyweight and Object Pool because both reuse existing objects. But the motivations, lifecycle, and concurrency models differ significantly.

Flyweight and Object Pool have the following similarities:

- Each maintains a repository of objects

- Each tends to return an existing object rather than instantiate a new one upon demand

- Each has concurrency concerns, for example you want to ensure that two threads cannot acquire the same pooled object simultaneously

However, they have the following differences:

- Flyweight is a memory optimization, whereas Object Pool is a performance optimization

- Acquired Flyweight objects are shared by multiple clients at the same time, whereas acquired Object Pool objects are shared by multiple clients, but at most one client per object at any given time.

- Because Flyweight objects are shared simultaneously, their intrinsic state must apply to all clients, whereas because Object Pool objects are only used by one client at a time, they can have client specific state

- The number of Flyweight objects can grow as requested, whereas the number of Object Pool objects tend to be fixed, but they can also grow and shrink dynamically depending upon utilization if desired

- Flyweight always returns an object when acquired, whereas an Object Pool might not have any available objects when one is requested

- Flyweight objects are initialized via Lazy Initialization, whereas Object Pool objects are initialized at start up using eager initialization, but they can be implemented to use lazy initialization as well

- Flyweight object reclamation is optional, whereas Object Pool reclamation is required

Core Object Pool Design and Implementation

As mentioned above, Object Pool’s structure is similar to Flyweight’s structure. My design and implementation example does not have a specific domain in mind, so class and interface names will not indicate what they do within the context of a domain. Their names indicate how they manage pooled objects.

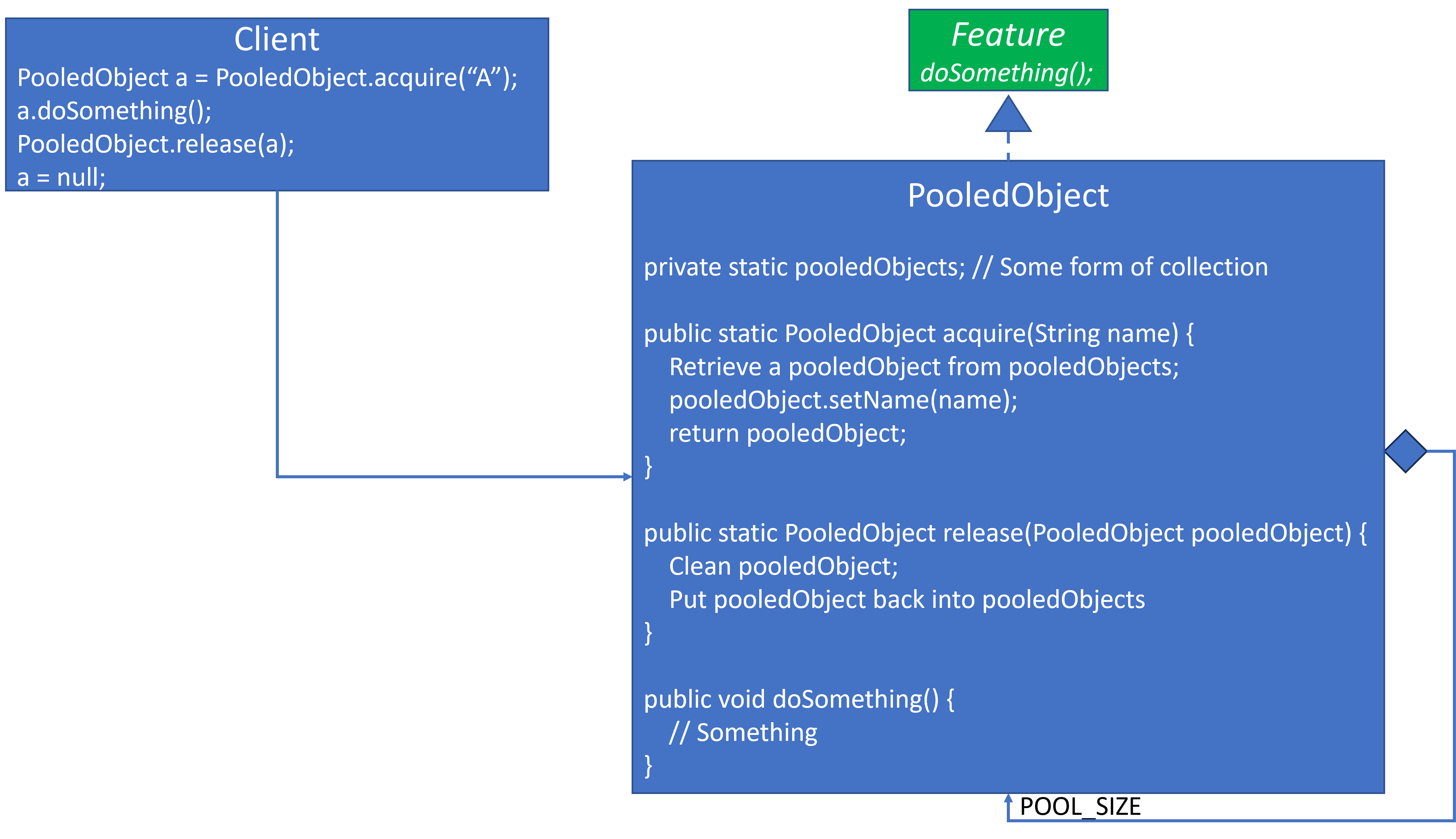

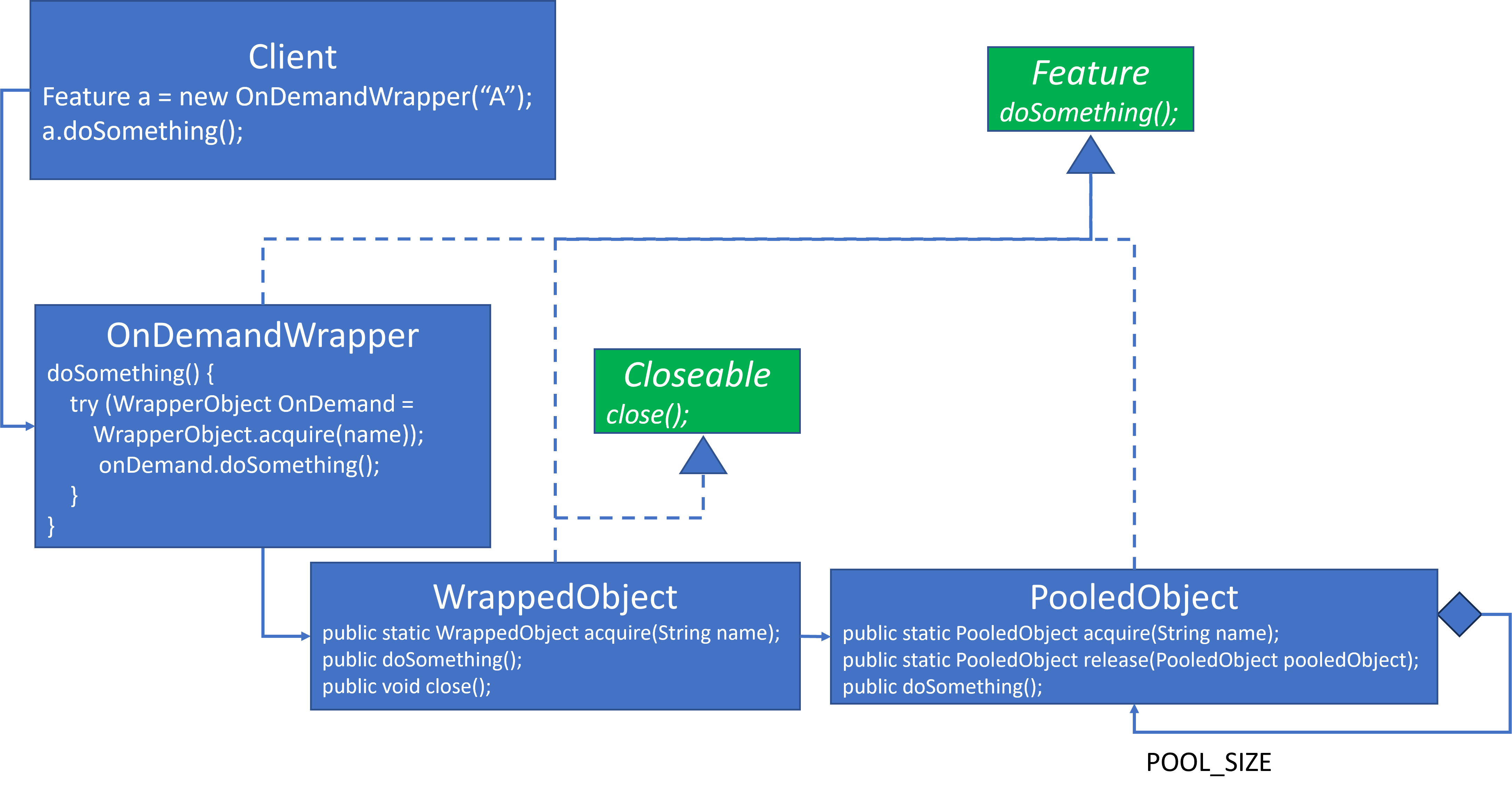

Here are some highlights from the design:

Featuredefines a basic contract withdoSomething().PooledObjectcontains the bulk of the Object Pool structure. It maintains a collection ofpooledObjectsalong with staticacquire()andrelease()methods, which manage the objects withinpooledObjects.Clientis not part of the pattern design specifically, but it’s important to feature how the client interacts with the pattern design.

PooledObject

Here is a Java implementation, which provides more implementation details:

- The

PooledObjectinstances can reside in almost any sort of container. I chose a queue with a fixed size of 3. - The

PooledObjectsare added toobjectPoolvia a static method, which is an example of eager initialization. As an alternative,PooledObjectscould be added only when needed until the pool has been filled. I am adding them viarelease(PooledObject)since initialization and reclamation share the same add-to-pool behavior, which justifies reusing the same method, even if the term release doesn’t scream initialization. - BlockingQueue is thread-safe.

- I added

idtoPooledObjectto uniquely identify each object in the pool. It’s not critical to the design. nameis state information provided by the client when acquiring a pooled object. It’s provided only as an example for the object’s state.acquire(String name)retrieves aPooledObjectfromobjectPool, initializes its state with the client provided name and returns it.release(PooledObject)cleans the instance by setting the name to null and adds it back to theobjectPoolqueue. It also confirms that a double-release won’t occur, which could introduce difficult to detect issues subsequently.

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class PooledObject implements Feature {

private final static int POOL_SIZE = 3;

private static BlockingQueue<PooledObject> objectPool = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(POOL_SIZE);

static {

for (int i = 0; i < POOL_SIZE; i++) {

try {

release(new PooledObject(i));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

private final int idNumber;

private String name;

private PooledObject(int idNumber) {

this.idNumber = idNumber;

System.out.format("Creating PooledObject idNumber=%d\n", idNumber);

}

public static PooledObject acquire(String name) throws InterruptedException {

PooledObject pooledObject = objectPool.take(); // Blocks if pool empty

pooledObject.setName(name);

return pooledObject;

}

public static void release(PooledObject pooledObject) throws Exception {

if (objectPool.contains(pooledObject)) throw new IllegalStateException("Object already released");

pooledObject.setName(null); // Cleans the object before returning it to the pool.

objectPool.put(pooledObject); // Blocks if pool full

System.out.format("Release %s by adding it to objectPool\n", pooledObject.toString());

}

private void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.format("Do something with %s\n", toString());

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("PooledObject idNumber=%d, name=%s", idNumber, name);

}

}

A complete implementation of the above is available at Core Object Pool Implementation.

release(PooledObject) cleans the released instance by setting the name to null. If object state isn’t scrubbed in release(PooledObject) then we run the risk of state provided by one client remaining in the state of the pooledObject when acquired by another client. Our Object Pool would become a Cesspool, and no one wants a dirty pool.

This example only has to clean name. Pooled objects with more state would require more cleaning which would probably be extracted into its own method named reset() or clearForReuse().

Cleaning a released object like spraying disinfectant into bowling shoes when they are returned or rewinding VCR cassettes when they are returned.

Client Code

Here is the client code:

PooledObject a = PooledObject.acquire("A"); // Take one object from pool

a.doSomething(); // Perform some operation

PooledObject.release(a); // Return it to pool

a = null; // Local reference cleared

While PooledObject provides the release(PooledObject) method, it’s the client’s responsibility to call it.

I have mentioned object reclamation a few times in previous blogs:

- Memory Leaks in the Factory blog

- Sin of Omission in the Proxy blog

- What the GoF Missed in the Creational Design Patterns Introduction blog

- Memory Leaks in the Singleton blog

- Memory Leaks in the Flyweight blog

I will continue the theme here. The GoF presented different patterns to create objects, but they did not address what to do with the object once it was no longer needed. Memory management is critical in C++, which was one of their two example languages. Some of their examples leaked memory.

Memory management isn’t quite as critical in Java, since Garbage Collection will tend to handle it for us.

The Object Pool pattern is a different case. We cannot rely upon garbage collection. In fact, we don’t want the pooled object to be collected. They’re in the Object Pool, because their creation is resource intensive. Once created, we want them to remain available for the duration of the process’ execution.

We need clients to release their objects back to the pool when they no longer need them. If they do not, then we run the risk of a drained pool. This would be like video store patrons renting movies and never returning them. The store’s shelves would become empty.

I also had the client clear the local reference above by setting it to null as an additional safety consideration. Once an object has been released, the client should not reference it subsequently, since it may have been acquired by another client.

Pool Exhaustion

Even with clients releasing their objects reliably and consistently, we can still end up with an empty pool. There may be more requesting clients than pooled objects. For example, the implementation example initialized the object pool with three objects. What if a fourth client requested one?

Object Pool introduces a failure mode that other creational patterns don’t: exhaustion. When all objects are checked out, what should happen?

| Strategy | Behavior When Pool Is Empty | Pros | Cons | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Wait | Caller waits until another client releases an object | Simple to implement; predictable; no failures | Can deadlock or stall threads indefinitely | Low-contention systems; controlled environments |

| Block Wait + Timeout | Caller waits up to a specified timeout, then fails | Prevents indefinite waiting; easier debugging | Timeout handling adds complexity; still can stall briefly | Systems needing reliability and bounded latency |

| Throw Immediately | Pool immediately rejects the request with an exception | Fast failure; callers react immediately | Can cause cascading failures without careful handling | High-throughput, low-latency systems; circuit-breaker setups |

| Create New Object on Demand | Dynamically grows pool beyond its initial size | Avoids failures; flexible scaling | Can defeat the whole purpose of pooling; potential resource exhaustion | Variable or bursty workloads |

| Fail Fast with Metrics/Logging | Immediately returns error and logs details | Excellent observability; supports operational awareness | Still fails requests; requires good monitoring responses | Production systems with SRE/DevOps observability |

Final Core Design and Implementation Thoughts

My implementation example doesn’t keep track of client acquired objects. In addition to the objectPool queue, we might want to also maintain the set of acquired objects. We might want to do this for pooled object integrity. If your pool accepts arbitrary objects in release(PooledObject), you do not have a pool, you have a vulnerability. My release(PooledObject) will allow any object to be added to the pool, including one that might be malicious.

If the ObjectPool maintains all pooled objects whether they are currently being used by clients or waiting to be acquired, then we would be more likely to identify and prevent foreign, potentially malicious, objects being injected into the pool via release(PooledObject). That is, do as I say, not as I do.

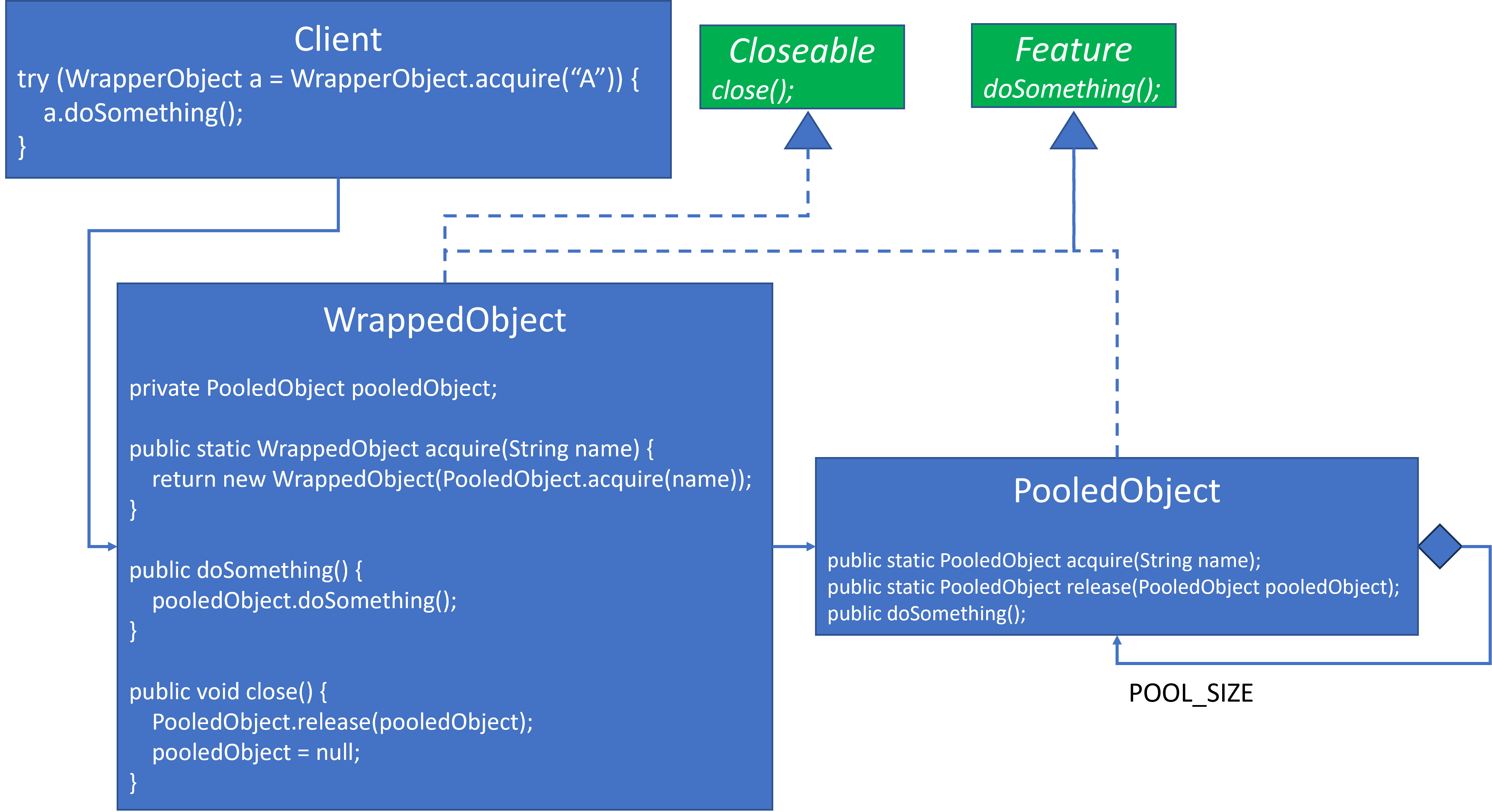

Proxy Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation

Before we dive into the Proxy-wrapped version, let’s review the limitations of the client-managed cleanup model. The core design and implementation listed above places a lot of responsibility upon the client to release the object and clear it locally. I don’t trust developers to get that right. I wouldn’t even trust myself to get it right.

When I was a C++ developer I used the Resource Allocation Is Instantiation (RAII) idiom to manage this. RAII is used for classes that have start and finish operations, such as a mutex lock/unlock and a database open/close.

RAII is a Proxy. Its constructor executes the start operation. Its destructor executes the finish operation.

The proxy wrapper object is instantiated upon the stack. When its constructor is executed, it executes the start operation. When the object exits its current scope whether it reaches the end of the scope, returns or an exception is thrown, the object is popped off the stack, and its destructor is executed, which executes the finish operation. It’s a nice way to ensure that start/finish operations always execute in pairs. Once I learned of RAII and started using it, I no longer had to worry about leaving a mutex locked because of an unexpected exception being thrown.

However, Java doesn’t have deterministic destructors nor are objects instantiated on the stack. Java doesn’t support RAII in the same form that C++ can. But we can approximate RAII using try-with-resources or explicit proxy wrappers.

Here’s a design that adds a WrappedObject in front of the PooledObject:

WrappedObject has taken on the client’s release responsibility from the previous design and implementation:

class WrappedObject implements Feature, Closeable {

private PooledObject pooledObject;

private WrappedObject(PooledObject pooledObject) {

this.pooledObject = pooledObject;

}

public static WrappedObject acquire(String name) throws Exception {

return new WrappedObject(PooledObject.acquire(name));

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

pooledObject.doSomething();

}

@Override

public void close() throws IOException {

if (pooledObject == null) {

// Already closed or never initialized - nothing to do.

return;

}

try {

PooledObject.release(pooledObject);

pooledObject = null;

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

Setting the internal pooledObject reference to null in close() prevents accidental reuse after close and helps prevent subtle client bugs.

Now that WrappedObject has taken on the release and clean up responsibility for the client, the client’s code becomes much nicer and safer with:

try (WrappedObject a = WrappedObject.acquire("A")) {

a.doSomething();

}

A complete implementation of the above is available at Proxy Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation.

The Sin of Omission, Revisited

I was about to write more about RAII, but since I’ve already addressed it in Sin of Omission, I’ll only repeat the highlights:

- The GoF used different method names for each of their creational design patterns. Their contract method names indicated how the object was created, which I felt violated encapsulation.

- I prefer contract method names that make sense from the client’s point of view indicating what contract method does rather than how it does it. That is, I prefer a contract that’s designed from the outside in rather than from the inside out. I prefer

acquire()as my creational contract method name, since the client uses it to acquire an object without knowing how the object is acquired. - The GoF didn’t address object reclamation or memory clean up. The memory for some creational pattern acquired objects should be reclaimed, such as memory from a Factory, whereas some memory should not be reclaimed, such as memory from a Singleton. This is mostly not an issue for memory managed languages with garbage collection, such as Java, but it’s an issue for non-garbage collected languages, such as C++. Some of the GoF’s creational design pattern example C++ code leaks memory.

- In addition to using a standard

acquire()method name, I prefer to include therelease(Reference)method to reclaim objects when they are no longer being used by the client. I don’t always do this in Java, but I declaredrelease(Reference)consistently when I was a C++ developer. I even did this for Singleton, for which itsrelease(Reference)would be a no-op, since I wanted consistency in all of my creational contracts. I wantedacquire()andrelease(Reference)to always be called in pairs. - I never trusted developers to call

acquire()andrelease(Reference)consistently in pairs, since this required them to read and understand the documentation. I knew they would find and callacquire()since it was the only mechanism that would acquire an object, but I didn’t trust them to consistently read and understand that they had to callrelease(Reference)as well. Their code would appear to work even if object references were not released. They would leak memory or other resources, but they wouldn’t suffer the consequences of their leaking code until production. Therefore, I provided an RAII wrapper that ensured thatacquire()andrelease(Reference)were always called in pairs. An added bonus to the RAII wrapper was that no additional documentation was needed by the developers. C++ developers could instantiate the RAII wrapper on the stack locally, or they could instantiate it in the heap via a call tonew RaiiWrapper(), but then they explicitly took on the responsibility todelete()the heap reference themselves. I didn’t need to document this. It’s documented in every C++ book that’s ever been published. Since Java doesn’t support RAII in the same way as C++, we need to rely upon try-with-resources for the same effect.

On Demand Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation

I’ll provide one more nuanced Object Pool design and implementation. This one wraps the try-with-resources statement within the method call, such that the client does not even need to be concerned with any implicit resource management. In this example, the client calls new() directly.

This is a special case, and it won’t work for all Object Pools. It only works as long as the client’s use of a pooled object can be scoped to one method call.

class OnDemandWrapper implements Feature {

private String name;

public OnDemandWrapper(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

try (WrappedObject onDemand = WrappedObject.acquire(name)) {

onDemand.doSomething();

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

Here’s the client’s code, which is barely worth listing:

Feature a = new OnDemandWrapper("A");

a.doSomething();

A complete implementation of the above is available at On Demand Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation.

Object Pool Trade-Offs

There are advantages and disadvantages to Object Pools.

Advantages:

- Avoid expensive instantiation repeatedly

- Limit the number of active objects (resource limiting)

- Performance improvements (GC pressure reduced, especially in GC languages)

Drawbacks and Risks:

- Complexity: more bookkeeping, acquiring/releasing

- Memory bloat: pooled objects retain memory even when idle

- Pool exhaustion risk

- Clients forgetting to release leading to leaks

- Overuse, especially when the objects are not resource intensive

- If the object is cheap to construct or mostly stateless, pooling is unnecessary and may reduce throughput

Summary

The Object Pool pattern offers real performance and resource-management benefits when used for the right reasons. It shines when objects are truly expensive to create and when a system needs predictable, bounded resource usage. But pooling also introduces new responsibilities: careful cleaning, clear ownership rules, and thread-safe coordination. Before adopting it, measure your bottlenecks, understand the trade-offs, and ensure your team is disciplined about the lifecycle of pooled objects. When implemented thoughtfully, Object Pools can be a powerful tool in a software engineer’s design toolbox.

References

- Wikipedia Object Pool Design Pattern

- Source Making Object Pool Design Pattern

- Object Pool - Blog by GameProgrammingPatterns.com

- Object Pool Pattern in Java: Enhancing Performance with Reusable Object Management - Blog by Java-Design-Patterns.com

- Introduction to Object Pooling - Blog by unity.com

- Create an object pool by using a ConcurrentBag - Microsoft article

- ObjectPools - Performance Engineering in Java - Video by kevgol0

- Level up your code with game programming design patterns: Object pool; Tutorial - Video by Unity

- The Object Pool - Programming Design Patterns - Ep 4 - C++ Coding - Video by Code, Tech, and Tutorials

- and for more, Google: Object Pool Design Pattern

Complete Demo Code

Here’s the entire implementation up to this point as one file. Copy and paste it into a Java environment and execute it. If you don’t have Java, try this Online Java Environment. Play with the implementation. Copy and paste the code into Generative AI for analysis and comments.

Core Object Pool Implementation

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

public class ObjectPoolDemo1 {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

PooledObject a = PooledObject.acquire("A"); // Take one object from pool

a.doSomething(); // Perform some operation

PooledObject.release(a); // Return it to pool

a = null; // Local reference cleared

// This cycle repeats, showing safe reuse of pooled resources.

PooledObject b = PooledObject.acquire("B");

b.doSomething();

PooledObject.release(b);

b = null;

PooledObject c = PooledObject.acquire("C");

PooledObject d = PooledObject.acquire("D");

c.doSomething();

d.doSomething();

PooledObject.release(d);

d = null;

PooledObject.release(c);

c = null;

// This confirms that the local references have been cleared, but the originals are still in the pool.

System.out.println(a);

System.out.println(b);

System.out.println(c);

System.out.println(d);

PooledObject e = PooledObject.acquire("E");

e.doSomething();

PooledObject.release(e);

}

}

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class PooledObject implements Feature {

private final static int POOL_SIZE = 3;

private static BlockingQueue<PooledObject> objectPool = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(POOL_SIZE);

static {

for (int i = 0; i < POOL_SIZE; i++) {

try {

release(new PooledObject(i));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

private final int idNumber;

private String name;

private PooledObject(int idNumber) {

this.idNumber = idNumber;

System.out.format("Creating PooledObject idNumber=%d\n", idNumber);

}

public static PooledObject acquire(String name) throws InterruptedException {

PooledObject pooledObject = objectPool.take(); // Blocks if pool empty

pooledObject.setName(name);

return pooledObject;

}

public static void release(PooledObject pooledObject) throws Exception {

if (objectPool.contains(pooledObject)) throw new IllegalStateException("Object already released");

pooledObject.setName(null); // Cleans the object before returning it to the pool.

objectPool.put(pooledObject); // Blocks if pool full

System.out.format("Release %s by adding it to objectPool\n", pooledObject.toString());

}

private void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.format("Do something with %s\n", toString());

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("PooledObject idNumber=%d, name=%s", idNumber, name);

}

}

Proxy Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

import java.io.*;

public class ObjectPoolDemo2 {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

try (WrappedObject a = WrappedObject.acquire("A")) {

a.doSomething();

}

try (WrappedObject b = WrappedObject.acquire("B")) {

b.doSomething();

}

try (WrappedObject c = WrappedObject.acquire("C");

WrappedObject d = WrappedObject.acquire("D")) {

c.doSomething();

d.doSomething();

}

try (WrappedObject e = WrappedObject.acquire("E")) {

e.doSomething();

}

}

}

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class WrappedObject implements Feature, Closeable {

private PooledObject pooledObject;

private WrappedObject(PooledObject pooledObject) {

this.pooledObject = pooledObject;

}

public static WrappedObject acquire(String name) throws Exception {

return new WrappedObject(PooledObject.acquire(name));

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

pooledObject.doSomething();

}

@Override

public void close() throws IOException {

if (pooledObject == null) {

// Already closed or never initialized - nothing to do.

return;

}

try {

PooledObject.release(pooledObject);

pooledObject = null;

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

class PooledObject implements Feature {

private final static int POOL_SIZE = 3;

private static BlockingQueue<PooledObject> objectPool = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(POOL_SIZE);

static {

for (int i = 0; i < POOL_SIZE; i++) {

try {

release(new PooledObject(i));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

private final int idNumber;

private String name;

private PooledObject(int idNumber) {

this.idNumber = idNumber;

System.out.format("Creating PooledObject idNumber=%d\n", idNumber);

}

public static PooledObject acquire(String name) throws InterruptedException {

PooledObject pooledObject = objectPool.take(); // Blocks if pool empty

pooledObject.setName(name);

return pooledObject;

}

public static void release(PooledObject pooledObject) throws Exception {

if (objectPool.contains(pooledObject)) throw new IllegalStateException("Object already released");

pooledObject.setName(null); // Cleans the object before returning it to the pool.

objectPool.put(pooledObject); // Blocks if pool full

System.out.format("Release %s by adding it to objectPool\n", pooledObject.toString());

}

private void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.format("Do something with %s\n", toString());

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("PooledObject idNumber=%d, name=%s", idNumber, name);

}

}

On Demand Wrapped Object Pool Design and Implementation

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

import java.io.*;

public class ObjectPoolDemo3 {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Feature a = new OnDemandWrapper("A");

a.doSomething();

a.doSomething();

a.doSomething();

a.doSomething();

Feature b = new OnDemandWrapper("B");

b.doSomething();

b.doSomething();

a.doSomething();

Feature c = new OnDemandWrapper("C");

Feature d = new OnDemandWrapper("D");

Feature e = new OnDemandWrapper("E");

Feature f = new OnDemandWrapper("F");

Feature g = new OnDemandWrapper("G");

a.doSomething();

b.doSomething();

c.doSomething();

d.doSomething();

e.doSomething();

f.doSomething();

g.doSomething();

a.doSomething();

}

}

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class OnDemandWrapper implements Feature {

private String name;

public OnDemandWrapper(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

try (WrappedObject onDemand = WrappedObject.acquire(name)) {

onDemand.doSomething();

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

class WrappedObject implements Feature, Closeable {

private PooledObject pooledObject;

private WrappedObject(PooledObject pooledObject) {

this.pooledObject = pooledObject;

}

public static WrappedObject acquire(String name) throws Exception {

return new WrappedObject(PooledObject.acquire(name));

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

pooledObject.doSomething();

}

@Override

public void close() throws IOException {

if (pooledObject == null) {

// Already closed or never initialized - nothing to do.

return;

}

try {

PooledObject.release(pooledObject);

pooledObject = null;

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

class PooledObject implements Feature {

private final static int POOL_SIZE = 3;

private static BlockingQueue<PooledObject> objectPool = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(POOL_SIZE);

static {

for (int i = 0; i < POOL_SIZE; i++) {

try {

release(new PooledObject(i));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e);

}

}

}

private final int idNumber;

private String name;

private PooledObject(int idNumber) {

this.idNumber = idNumber;

System.out.format("Creating PooledObject idNumber=%d\n", idNumber);

}

public static PooledObject acquire(String name) throws InterruptedException {

PooledObject pooledObject = objectPool.take(); // Blocks if pool empty

pooledObject.setName(name);

return pooledObject;

}

public static void release(PooledObject pooledObject) throws Exception {

if (objectPool.contains(pooledObject)) throw new IllegalStateException("Object already released");

pooledObject.setName(null); // Cleans the object before returning it to the pool.

objectPool.put(pooledObject); // Blocks if pool full

System.out.format("Release %s by adding it to objectPool\n", pooledObject.toString());

}

private void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.format("Do something with %s\n", toString());

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.format("PooledObject idNumber=%d, name=%s", idNumber, name);

}

}