Factory Design Patterns

How do you instantiate an object without knowing its type?

Introduction

I kicked the object reference resolution can down the road in previous Essential Design Patterns blogs. I said that I’d eventually get to it and sit tight. I’m done kicking the can. I’ll resolve it here … well at least I’ll start to resolve it here.

I only told half the story before with previous design patterns Command, Strategy, Template Method, Adapter where I only presented the intent and design of each pattern. These pluggable patterns were incomplete. Each featured concrete classes that need to be instantiated and plugged in to complete the functionality.

You Complete Me

Patterns that involve pluggable concrete classes are incomplete until a Creational Design Pattern completes them.

While object creation and configuration are implicit themes in the Gang of Four (GoF), I think they should have been more explicit about it. Their patterns presentations rarely complete the story, which I’ll try to do.

Ways To Instantiate Object Instances

The Problem with new

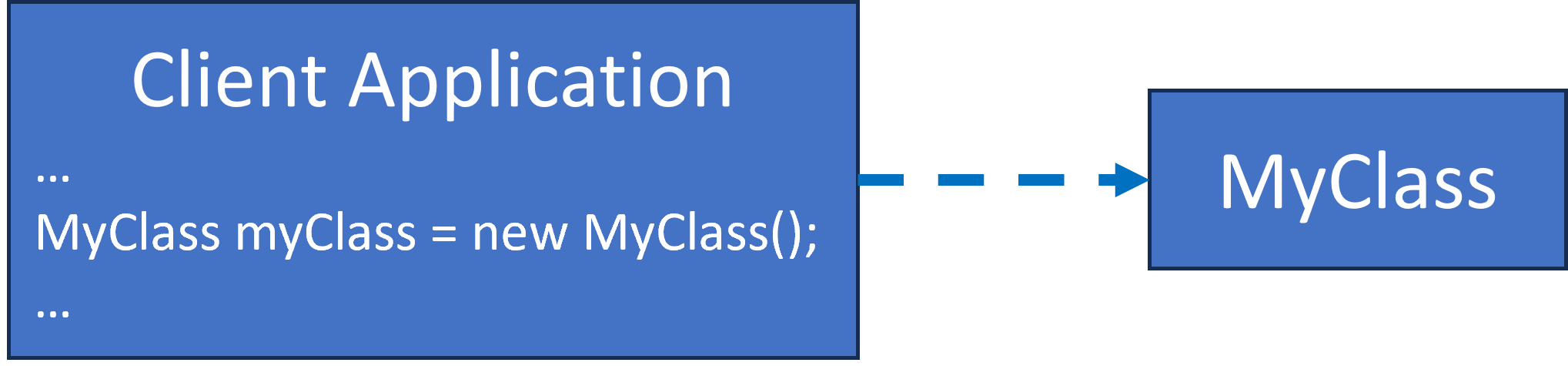

Steve Ardalis coined the phrase, New is Glue, in a 2012 blog. Any code that instantiates an object via a constructor directly, often calling new, will depend upon that class type. It will be glued to it.

We don’t want the Client Application to depend upon the objects that it uses. new will create a dependency.

We want to avoid using new to create domain objects as shown below.

Using new is usually fine for utilities, such as:

String name = new String()

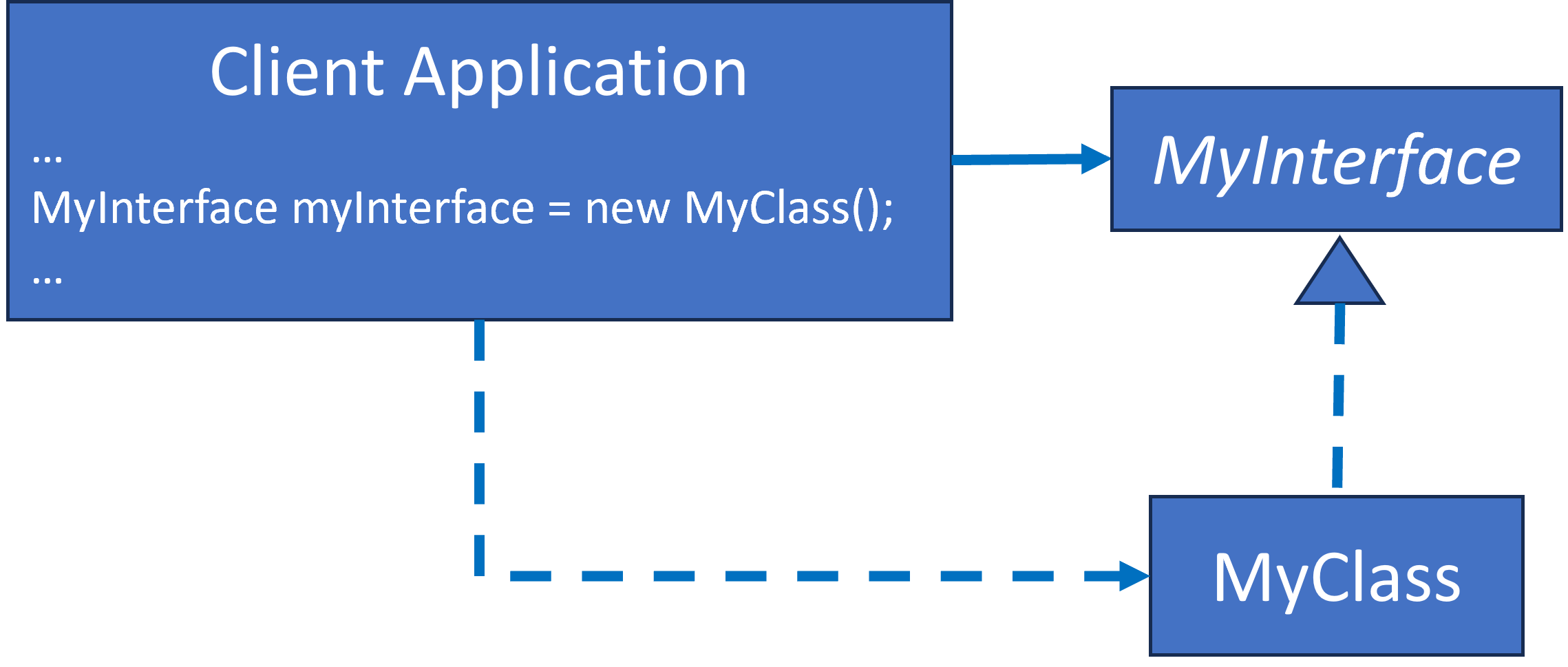

The GoF addressed this conceptually with their first design principle: Program to an interface, not an implementation. This principle states that the code should depend upon interfaces and not specific classes. But it doesn’t state how references to interfaces are resolved.

A naïve approach could look like this, where the Client Application declares the reference as an interface, but it’s still calling new to instantiate the reference.

The GoF continued their interface theme with their Creational Design Patterns, which complete the story for most design patterns when paired together. The Creational Design Patterns instantiate objects without the Client Application having direct knowledge of the class type for the instantiated object. The GoF were obsessed with encapsulating class type within a Creational Design Pattern so that the Client Application would not know the type.

Resolving Object References Without Calling new Directly

We have a bit of a paradox. We need to resolve references to interfaces without direct knowledge of the class type, but the only way to instantiate an object is via a constructor which requires direct knowledge of the class type. We can resolve this paradox with a little indirection. I can think of several ways to resolve an object reference without the Client Application calling new directly. The constructor is still invoked via new but never by the Client Application.

Factories

Static methods are associated with classes, not objects. Therefore, static methods can be invoked from the class without an object. Static method invocation is a technique favorited by the GoF in their Creational Design Patterns. It generally takes two forms:

- Factory Method

- Factory Class

Factory Method

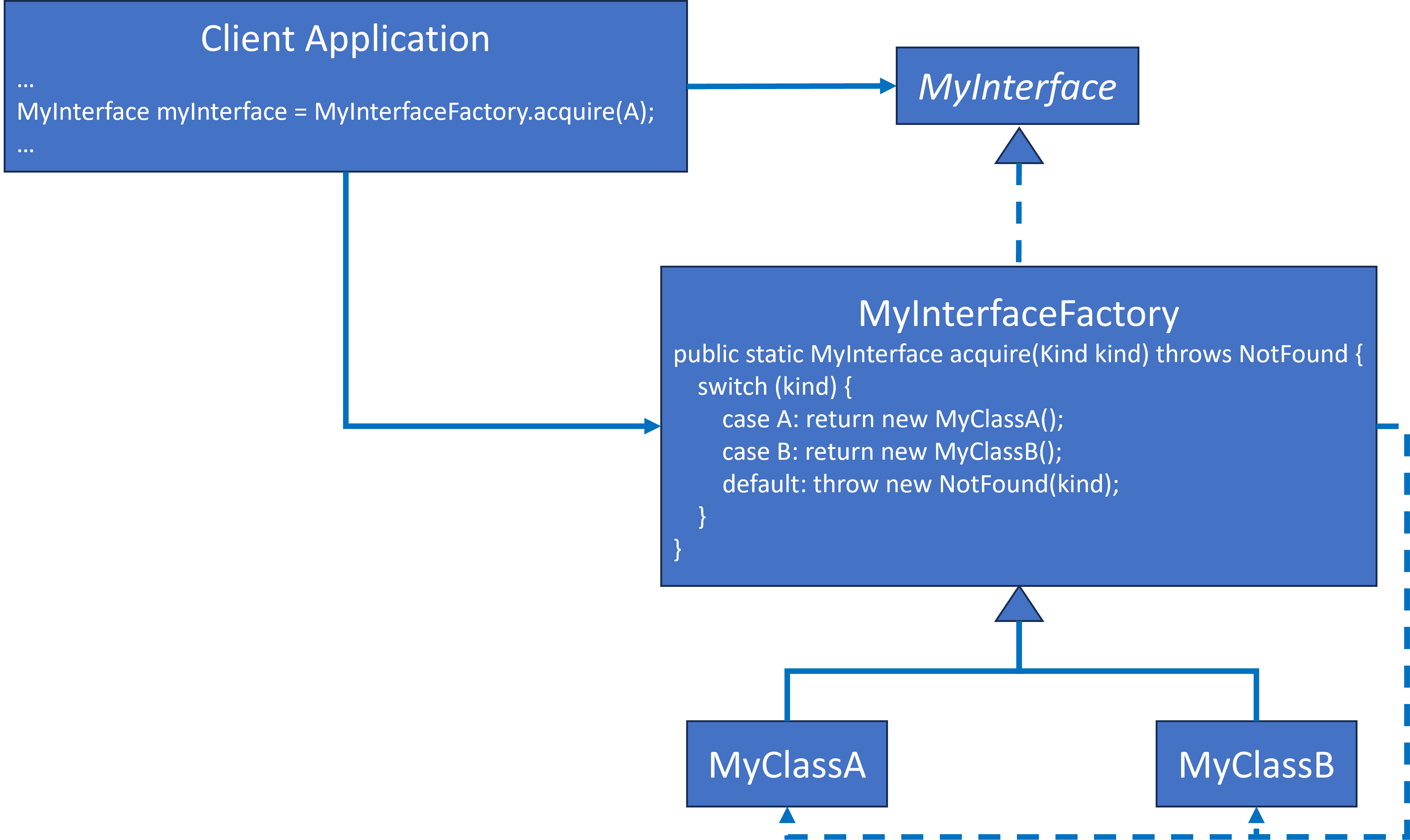

Here’s an example of Factory Method. The Client Application calls the static acquire(Kind) method, which returns a MyInterface object. Kind refers to the type of class that the Client Application may desire. Notice that acquire(Kind) can return a class instance of MyClassA and MyClassB for Kind A and B respectively. While the Client Application does know Kind it does not know MyClassA or MyClassB. MyInterfaceFactory could return any class for A or B if those classes extend MyInterface.

Factory Class

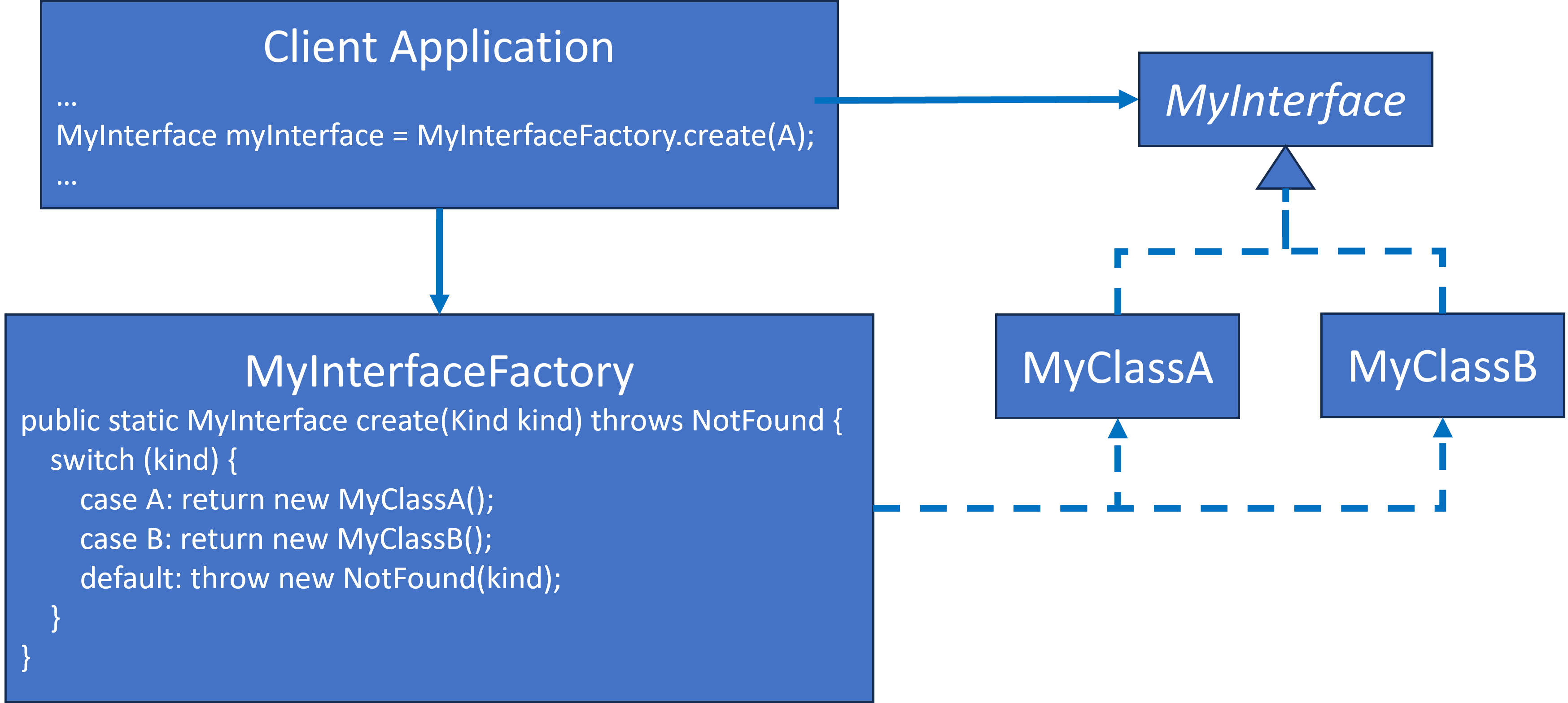

Factory Class is like Factory Method. The main difference is that the MyInterfaceFactory is not part of the MyInterface hierarchy. Notice that nothing changes from the Client Application’s point of view.

The GoF tend to feature the Factory Method technique, but I prefer the Factory Class technique. While it’s still a matter of personal choice, I prefer Factory Class over Factory Method, because:

- Java doesn’t support multiple inheritance; I don’t want to introduce a base class solely for the purpose of instantiating descendant objects.

- I prefer the separation of concerns with this design. The interface contract and its concrete implementations are separate from the mechanism that creates the object instances.

Abstract Factory

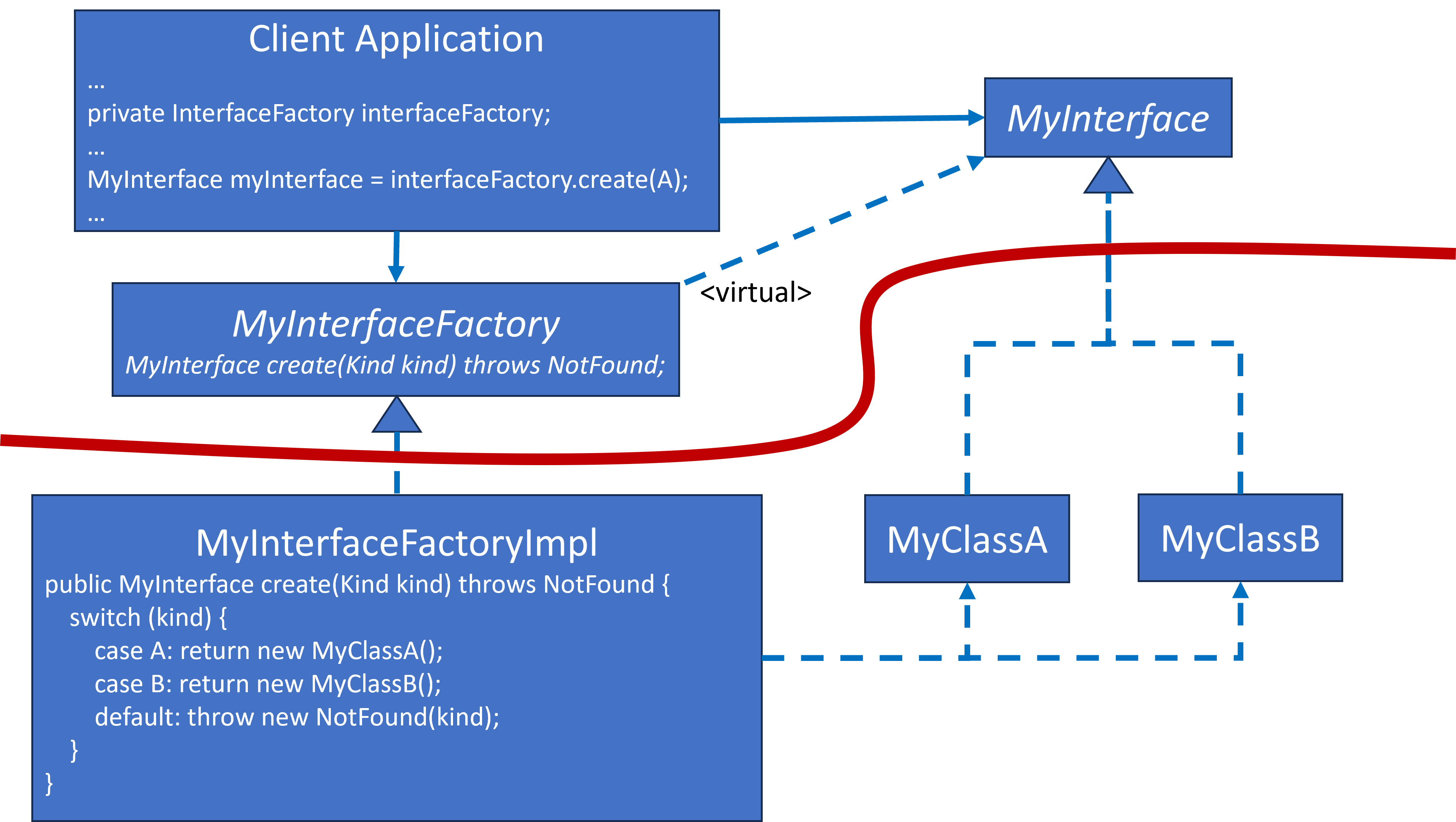

Abstract Factory is the first one you encounter in detail when reading the GoF book. It’s a bit overwhelming as the first pattern encountered. I’ve presented it here as a modification to the Factory Class:

MyInterfaceFactoryis a new element. It’s an interface that defines a contract for creating an instance ofMyInterface.- Client Application is a little different. It doesn’t access a static class method. It accesses

acquire(Kind)via a reference tointerfaceFactory. And I’m going to kick the resolution can ofinterfaceFactorydown the road once more. Its resolution will be in the next blog. See: Dependency Injection. - The virtual creation line from

MyInterfaceFactorytoMyInterfaceis only to highlight that as far as the Client Application is concerned,MyInterfaceFactorycreatedMyInterface, but it is actually created byMyInterfaceFactoryImpl. - The curved line is not an implementation detail. It defines an architectural/design boundary. All the business logic abstraction resides above the line. All dependency details reside below the line. This gives us great freedom in plugging in different factory implementations for different needs, such as production dependencies or test double dependencies.

NOTE: The above diagram is inspired by a diagram in Bob Martin’s Clean Architecture book.

Gang Of Four Creational Design Pattern Inventory

The GoF Creational Design Patterns used the techniques listed above. In some cases, their patterns are mostly identical to the above, but they often provide additional features or context. I’ll list them with brief descriptions. See the references section below for more resources for specific Creational Design Patterns.

Factory Method

The GoF Factory Method is so close to what I described above that I don’t need to provide any additional context.

Singleton

Singleton ensures that only one instance of the class is ever created. It’s quite possibly the most overly used and incorrectly used design pattern. The GoF’s implementation is not thread safe. Singletons should not contain state unless that state applies to all Client Applications globally.

There are legitimate uses for Singleton. Just make sure you only use it for those reasons.

Flyweight/Multiton

Flyweight is not listed as a Creational Design Pattern by the GoF. It’s in the Structural Patterns group. It’s like Singleton in that it ensures a single object instance, but it does so based upon a unique key. There can be more than one instance of a class, but there can only be one instance for each unique key. This is why it’s also known as Multiton, which is a play on words with Singleton.

Object Pool

Object Pool is not in the GoF inventory. With an Object Pool, the number of possible Objects for a class is fixed. An Object Pool is usually used for classes where creation of the class is resource intensive. A Thread Pool is a type of Object Pool.

Object Pool has several additional considerations:

- An object in the pool needs to be sanitized before it can be reused.

- A policy is required when there’s a request for an object and all existing objects are being used. Possible policies include:

- Block Waiting

- Callback notification availability

- Unavailable resource exception

- Expanding the pool

Abstract Factory

The GoF Abstract Factory is close to what I described above, but Abstract Factory descriptions usually focus upon the ability create consistent instances of interface family types. That is, they help ensure a consistent set of objects when several interfaces need to interact consistently. For example, you wouldn’t want one factory that returned a production object another one that returned a test object to interact. Abstract Factory helps avoid that.

Abstract Factory is a Factory of Factory of Factory Methods.

Prototype

Prototype is different from Factories. Factory patterns often encapsulate new within a static method. Factories still need to know the class type. Prototype’s mechanism encapsulates new within a non-static method. A new object is acquired with Prototype by calling the non-static method of an existing object, which calls its own constructor via new and returns a new object instance.

Prototype includes a repository. Breeder objects are created and added to the Prototype repository. Each object is identifiable via a key, which could be a name or any unique key. When a new object is needed, the repository is searched using the key. If a breeder object is found for that key, then its non-static method is called, and the object it instantiates is returned.

Prototype doesn’t know class types. It can return a new object for any breeder object in its repository. This makes it a flexible creational pattern when the set of possible class types aren’t known in advance.

Builder

I don’t think I can describe Builder in a paragraph or two and give it justice. I’ll just state that it’s useful when you need to initialize and assemble a composite of objects rather than a single object instance.

Builder is the second design pattern in the GoF book. If Abstract Factory doesn’t confuse the casual reader, then Builder will. This is usually around the place where I put the book back on the shelf the first few times that I tried to read it.

See: Builder Design Pattern Introduction.

Creational Design Patterns Are Not Always Used In Isolation.

The creation techniques and the Creational Design Patterns can be used in combination. For example, in the Factory Method or Factory Class examples above, the statements for each case in the switch block called new. Each of these could be resolved with another creational design pattern. It might look something like this:

public MyInterface acquire(Kind kind) throws NotFound {

switch (kind) {

case A: return MyClassA.acquire();

case B: return MyClassB.acquire();

default: throw new NotFound(kind);

}

}

Creational Design Pattern … Goofs?

I think the GoF goofed in at least two aspects of their Creational Design Pattern presentation.

What Happened to Encapsulation?

The GoF were obsessed with encapsulation. Don’t let the Client Application know the class type. Then they feature method names for each Creational Design Pattern that suggests the creation mechanism:

- Factory Method and Abstract Factory feature

create()ormake() - Singleton features

instance()orgetInstance() - Builder features

construct() - Prototype features

clone()

Using method names that indicate creation mechanism breaks encapsulation. Let’s consider the Client Application. Its main concern is acquiring a method. It doesn’t care about the creation mechanism. That’s why I used acquire() in all of my examples.

Memory Leaks?

The GoF tend to use C++ for their creational design pattern examples, and this is C++ from 1995.

I don’t recall any sample code where they delete any objects created via their design patterns. Some of their examples leak memory. I assume they assumed that developers would know enough to handle the memory management.

When I was a C++ developer, I’d pair acquire() with release(object) when I designed creational mechanisms. When the Client Application was done with an object, it would release it. The release(object) method would manage any cleanup that was needed. Keep in mind that Factory Method objects would be deleted. Object Pool objects would be cleaned and returned to the Pool. Singletons would not be affected. By adding release, the creation mechanism was also responsible for any clean up. The only developer responsibility was calling release.

I didn’t trust developers to always call release(object). So I used Resource Allocation Is Instantiation (RAII). A small wrapper class managed the object lifecycle. acquire() was called in the wrapper’s constructor and release(object) was called in its destructor. I’d had come full circle and completely encapsulated the use of creational design patterns within an object whose lifecycle was traditional C++.

Java has garbage collection, so memory management isn’t as necessary, but it shouldn’t be ignored. I don’t think there’s a need for release(object) in Java, but Singleton and Flyweight/Multiton can leak memory. Once these objects are allocated, they are never released. Weak references might be a way to ensure that their memory is recovered when no longer in use.

And Object Pool will always leak memory; although, a fixed amount of memory.

References

Previous blogs tended to focus upon one design pattern. This one expanded into several. There are too many for individual references. However, most Creational Design Patterns references tend to be clustered. I’ll present as many clusters as possible, since it should be relatively easy to find details for a specific design pattern.

There are many online resources with diagrams and implementations in different programming languages. Here are some free resources:

- My Introduction to Creational Design Patterns

- Wikipedia Creational Design Patterns

- Source Making Creational Design Patterns

- Refactoring Guru Creational Design Patterns

- DoFactory Creational Design Patterns

- Project Management Institute doesn’t have a Creational page. It only provides pages for three Creational patterns:

- and for more, Google: Creational Design Pattern

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

- Gang of Four Creational Design Patterns

- Agile Principles, Patterns, and Practices in C#, Chapter 29 (O’Reilly and Amazon)

- Clean Code: Design Patterns, Episode 26 video (Clean Coders and O’Reilly)

- Head First Design Patterns, Chapter 4 (O’Reilly and Amazon)