Strategy Design Pattern

When there’s more than one way to get the job done.

Settlers of Catan Victory

Victory is achieved in Settlers of Catan by acquiring Victory Points received via different criteria in the game. Players may use different strategies to receive these points. There are multiple ways to win this game.

The Strategy Design Pattern supports multiple options as well.

Strategy vs Command

The Strategy Design Pattern looks so much like the Command Design Pattern that you’d swear that they are the same. Both are based upon polymorphism. The difference is context and intent.

Command’s intent is the objectification of a function so that we can treat it as an object. The pattern doesn’t focus upon the nature of the function being objectified. Command’s primary concern is to make a function accessible anywhere an object is accessible.

Strategy’s intent is a more narrowly scoped contract focused upon what the client application wishes to accomplish. Strategy’s primary concern is to provide a means for the client application to accomplish its goal.

The contract, which is usually implemented as an interface, may consist of multiple cohesive methods. For example, if the contract’s single responsibility is persistence, then there may be four methods to Create, Read, Update and Delete business entities.

Separation of Concerns and Modularity

Strategy leverages Separation of Concerns and Modularity. It separates what the client application wishes to accomplish from how it will be accomplished.

The Strategy interface contract should be defined from the client application’s point of view. It should convey what the client application needs, not what the implementation can provide.

The client application should neither know nor care about its concrete dependencies since it does not have a direct dependency upon those concrete classes. This provides a lot of flexibility. The client application will only have knowledge of and a reference to the Strategy interface.

There may be multiple concrete classes that implement an interface contract. That is, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and I use this analogy with my sincerest apologies to Sparky T. Cat, who generally doesn’t appreciate my using that sort of language. The T. is for The.

There may be multiple concrete classes that implement an interface contract. That is, there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and I use this analogy with my sincerest apologies to Sparky T. Cat, who generally doesn’t appreciate my using that sort of language. The T. is for The.

The client application’s Strategy reference is resolved at runtime, and it can be updated dynamically. What’s more, the client application can have a collection of Strategy interface references, and each reference can be resolved with references from different concrete classes.

Reference resolution doesn’t get as much attention in Strategy and other similar design patterns as it probably should. The Gang of Four (GoF) provide a few vague suggestions, but I don’t feel they provide clear guidance.

I will provide my own thoughts as I continue with Essential Design Patterns blog entries, but I don’t want to get the cart before the horse. For now, assume that the Client Applications will have the Strategy references they require. (See: Factory Method and Dependency Injection)

Strategy’s Structure

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here’s the traditional Strategy UML class diagram from DoFactory.com:

Here are the elements and their relationships:

Strategyis an interface.AlgorithmInterface()is a method that declares the contract that fulfills a need of theContext(AKA Client Application). There may be several cohesive methods in the contract, not just one as depicted here. Algorithm is the term chosen by the GoF. It’s not my favorite term, but it appears repeatedly in descriptions of Strategy.Contextis the Client Application, and I will use the term Client Application rather than Context, since I feel that it’s a more accurate term. The Client Application delegates behavior responsibility to the Strategy interface via a reference to a Strategy object. The Client Application will maintain this reference, often as a private field attribute. Delegating to an interface demonstrates the first design principle: Program to an interface rather than an implementation.ConcreteStrategyA,ConcreteStrategyBandConcreteStrategyCare three different implementations of theStrategyinterface. There could be any number of concreteStrategyimplementation classes. The design does not dictate how many there must be.

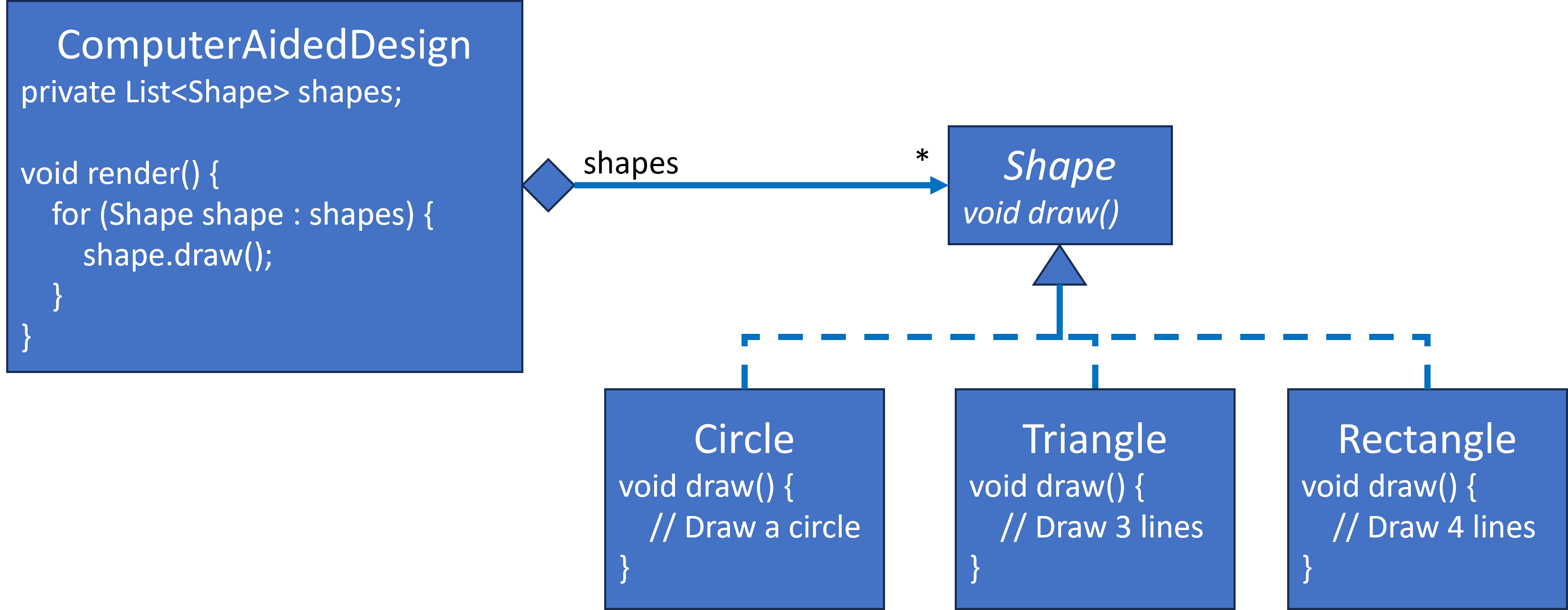

The Shape of Things to Come

Strategy is polymorphism. Let’s return to one of our old Object-Oriented friends that’s often used to describe polymorphism – Shape. Shape works perfectly well as an example for Strategy as well. Do a Google Image search on object-oriented programming shape UML and you’ll see examples that mirror the UML diagrams I’ve presented here for Strategy.

Here’s my version of a UML class diagram using Shape. The structure is almost identical to the traditional Strategy diagram shown above:

This is part of the design for a Computer Aided Design (CAD) client application. One of its operations is to render a set of shapes. We want to use Strategy so that the ComputerAidedDesign class does not depend upon the specific concrete Shape classes.

Shape is a Strategy, and its contract is for the Shape to draw itself.

While I didn’t add it, I could have also added additional contract operations such as perimeter and area with similar implementations in the concrete classes.

New Shapes, such as Oval, can easily be added without an impact upon existing classes. Oval would be another class that implements Shape.

Testing

Even if there’s only one concrete class that the Client Application would ever delegate to, you may still want to consider Strategy, and that would be for testing the Client Application code.

Strategy’s primary concern is to provide a means for the Client Application to accomplish its goal. It’s about supporting the interaction between the Client Application and the Strategy interface contract without tightly coupling the Client Application to a Concrete Strategy class. Strategy also allows us to test the Client Application/Strategy interaction without that tight coupling as well.

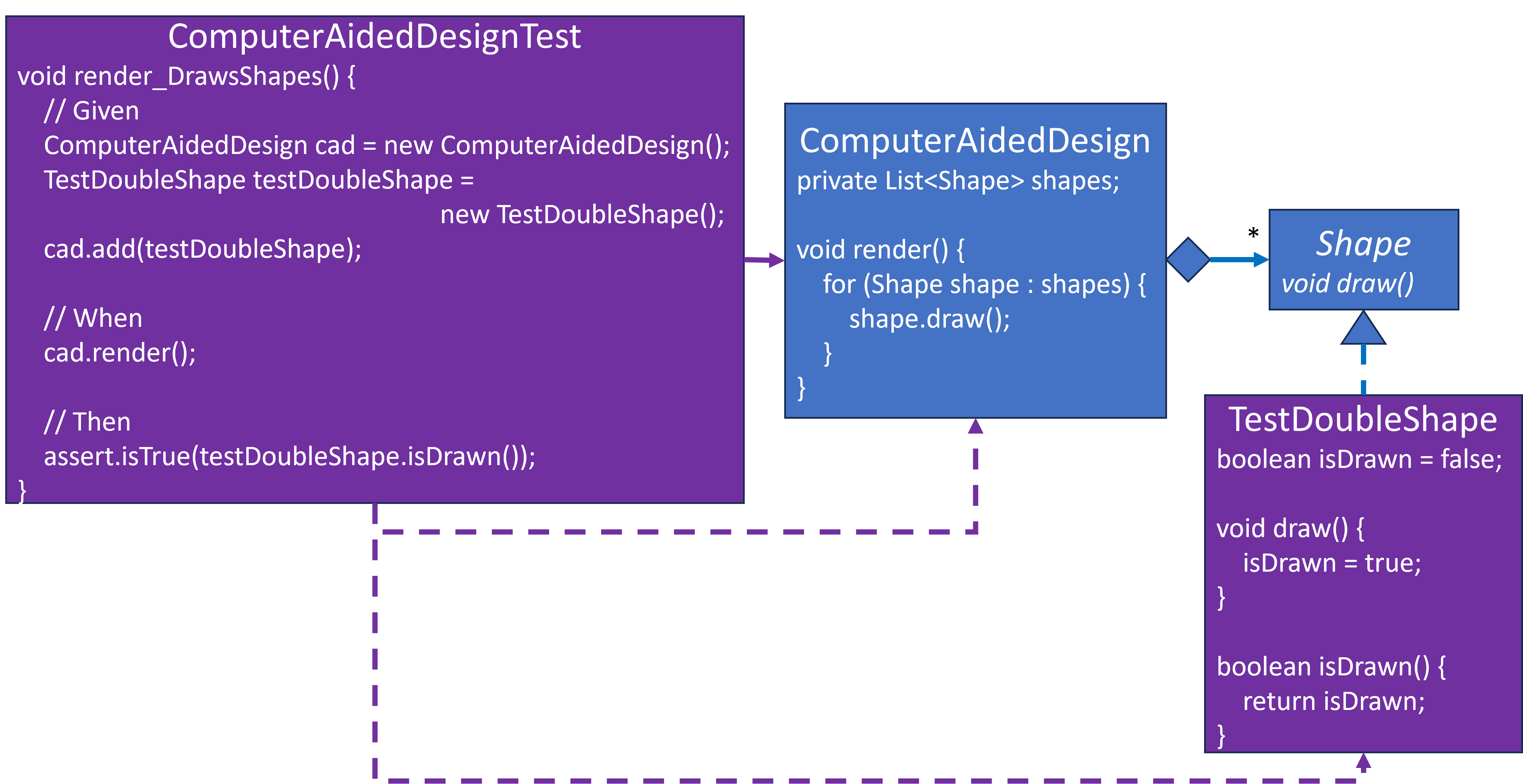

The diagram below is a UML sketch of how that might be done.

The ComputerAidedDesign and Shape elements are identical to the UML diagram above. The purple elements have been added for testing. ComputerAidedDesignTest runs a test scenario confirming that render draws shapes. TestDoubleShape emulates Shape behavior. It doesn’t draw anything, but it remembers that there had been a request for it to be drawn. I don’t want to drift too far astray from Strategy. Testing deserves its own set of blogs starting with The Conversion of a Unit Test Denier or … How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Unit Testing.

The modularity of Strategy may facilitate the testing of the Concrete Strategy classes as well since they don’t have any dependencies upon the Client Application code.

When to Consider Strategy

You could use Strategy for every class. That’s probably taking it a bit too far. Consider Strategy when delegating to behavior that requires external dependencies, such as a Database or an Internet call. Consider Strategy when delegating to behavior that resides in components elsewhere in the system, such as a service provided by another team. Consider Strategy to keep your code more modular and cleaner.

I may or may not consider Strategy for a class within my control. It would depend upon the size and sophistication of the class. The larger and more sophisticated the class the more I’d consider using Strategy.

I would not consider Strategy for most utility classes, such as String.

Summary

Strategy separates Client Application implementation from Concrete Class dependencies. Concrete Class references are assigned at runtime. They may be assigned only once, or they may be reassigned at any time. The Client Application might have a Container of Strategy references, and each can have its own Concrete Class reference as was shown with the Shape example.

Strategy provides flexibility via Separation of Concerns and Modularity. Strategy supports decoupled testing.

References

There are many online resources with diagrams and implementations in different programming languages. Here are some free resources:

- Wikipedia Strategy Design Pattern

- Source Making Strategy Design Pattern

- Refactoring Guru Strategy Design Pattern

- DoFactory Strategy Design Pattern

- Project Management Institute Strategy Design Pattern

- and for more, Google: Strategy Design Pattern

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

- Gang of Four Strategy Design Pattern

- Agile Principles, Patterns, and Practices in C#, Chapter 22 (O’Reilly and Amazon)

- Clean Code: Design Patterns, Episode 27 video (Clean Coders and O’Reilly)

- Head First Design Patterns (O’Reilly and Amazon)

Complete Demo Code

Here’s the entire implementation up to this point as one file. Copy and paste it into a Java environment and execute it. If you don’t have Java, try this Online Java Environment. Play with the implementation. Copy and paste the code into Generative AI for analysis and comments.

I wrote this demo code two and a half years after writing this blog. I asked ChatGPT for comments. It told me that it was closer to the Command Design Pattern than Strategy. Its main suggestion was to declare this Strategy interface:

interface DrawStrategy {

void draw(ShapeData data);

}

The main difference is that my Strategy interface defines Shape. Other than that, they’re the same. I think my version still demonstrates multiple implementations for the same interface, so I’m sticking with it.

import java.util.*;

public class StrategyDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Test.test();

ComputerAidedDesign cad = new ComputerAidedDesign();

cad.add(new Circle());

cad.add(new Triangle());

cad.add(new Rectangle());

cad.render();

}

}

class ComputerAidedDesign {

private List<Shape> shapes = new LinkedList<>();

public void render() {

for (Shape shape : shapes) {

shape.draw();

}

}

public void add(Shape shape) {

shapes.add(shape);

}

}

////////// STRATEGY CONTRACT /////////

interface Shape {

void draw();

}

////// STRATEGY CONCRETE CLASSES /////

class Circle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Draw a Circle");

}

}

class Triangle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Draw a Triangle");

}

}

class Rectangle implements Shape {

@Override

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Draw a Rectangle");

}

}

/////////////// TESTS ////////////////

class TestDoubleShape implements Shape {

private boolean isDrawn = false;

@Override

public void draw() {

isDrawn = true;

}

public boolean isDrawn() {

return isDrawn;

}

}

class Test {

public static void test() throws Exception {

drawsShapes();

System.out.println("Tests Passed");

}

private static void drawsShapes() throws Exception {

// Given

ComputerAidedDesign cad = new ComputerAidedDesign();

TestDoubleShape shape1 = new TestDoubleShape();

cad.add(shape1);

TestDoubleShape shape2 = new TestDoubleShape();

cad.add(shape2);

// When

cad.render();

// Then

assertEquals(true, shape1.isDrawn());

assertEquals(true, shape2.isDrawn());

}

private static void assertEquals(boolean expected, boolean actual) throws Exception {

if (expected != actual) {

System.out.format("expected=%b, actual=%b\n", expected, actual);

throw new Exception();

}

}

}