Hexagonal Architecture and how it compares to and contrasts with Clean Architecture

Hexagonal vs Clean where the Devil is in the Details

Introduction

This continues the Hexagonal Architecture series with how Hexagonal Architecture compares to and contrasts with Clean Architecture. Understanding one design helps to understand the other.

I feel like I’ve mentioned Clean Architecture by Bob Martin almost as much as I’ve mentioned Hexagonal Architecture by Alistair Cockburn in the Hexagonal Architecture series so far. In this blog post, I will compare and contrast Hexagonal Architecture and Clean Architecture as I view them.

I encountered Clean Architecture first, and it led me to Hexagonal Architecture. I had watched Bob Martin’s Clean Architecture videos via O’Reilly and I read his Clean Architecture book. These resources are available, but they can only be accessed via a subscription service or purchase. See the References at the bottom of this page. Fortunately, Martin blogs about Clean Architecture, and he has presented it several times at different conferences. He conveys most of the basics through these resources, which are freely available. These summarized resources take much less time to consume than the paid videos or book, and they tend to contain most of the important details.

Basic Similarities and Differences

The Hexagonal Architecture and Clean Architecture share the same basic design philosophy, along with the Onion Architecture, that domain information should be cocooned within the design with external dependencies pushed to the design edges. Domain information should not depend upon the external dependencies. The differences are mostly in details and terminology.

Hexagonal Architecture focuses upon the structure of the design. Clean Architecture provides more detail and context. Hexagonal Architecture is syntax. Clean Architecture is semantics. Hexagonal Architecture is about structure. Clean Architecture is about behavior. In a sense, Clean Architecture conceptually extends Hexagonal Architecture.

Screaming Architecture

Bob Martin often starts his Clean Architecture presentations with Screaming Architecture. Martin proposes that the first thing one should notice with an architecture is what the application does and not how it’s built. One’s first impression should be that the application is in the finance, medical or social media domain. It should not be that it’s developed on Ruby on Rails or Spring Boot.

Martin uses building floor plans to illustrate his point. Floor plans convey the type of building, the rooms, how they are connected and their function. If it does convey the building materials, it tends to be more subtle.

When most people are looking to buy a home, they’re probably more concerned with the number of rooms, flow between rooms, number of bathrooms, etc. and not so much the gauge of the electrical wiring.

Architectures should support feature behaviors not the technical details. Martin highlights this with the following:

- A good architecture allows major decisions to be deferred!

- A good architecture maximizes the number of decisions NOT made.

How many times have you witnessed an architecture where the first decision was choosing the database vendor?

Martin considers external dependencies, such as the database vendor, the decisions deferred or not made. The longer you delay a decision the more time and information you’ll have to make the correct decision. Use an architecture that allows you to delay those decisions.

Clean Architecture … Two Diagrams

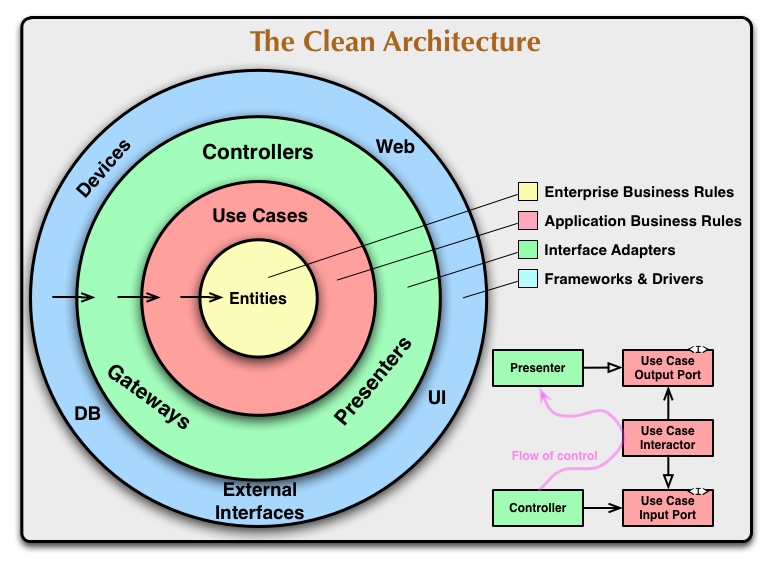

There are primarily two diagrams that convey Bob Martin’s Clean Architecture:

- The High-Level Clean Architecture Diagram, which lists the elements of the design, but not with much detail.

- The UML Class Architecture Diagram, which provides class-level detail, but its alignment to the high-level diagram isn’t necessarily obvious.

High-Level Clean Architecture Diagram

This diagram defines dependencies and constraints much like Hexagons do, except that Martin uses circles rather than hexagons. He color coded the rings and provided some context as to what sort of entities reside in each ring. He provides a few examples in the rings themselves.

The arrows on the left of the rings pointing toward the center to indicate dependency and knowledge flowing inward. I think the arrow between the blue and green rings is pointing the wrong direction. I think it should be pointing outward. I’ll address this later.

NOTE: The number of rings is not set in stone. Each project can tweak this as needed.

Hexagonal Architecture has the same basic structure, but the focus is different. The circles between the rings would correspond to hexagons. It doesn’t matter whether they’re circles or hexagons. The region between boundaries is more important than the shape of the boundary.

Alistair Cockburn favors the name Ports and Adapters over Hexagonal Architecture. Ports and Adapters describes the design in terms of these structures. These elements only apply to either side of the Salmon and Green Rings in the high-level Clean Architecture diagram. Clean Architecture tends to focus upon other aspects of the design as well.

The Clean Architecture diagram is more about intent, without focusing upon structural mechanisms, whereas the Hexagonal Architecture diagram is more about the structural mechanisms without focusing upon intent. Both are telling the same story. The difference is how the story is told.

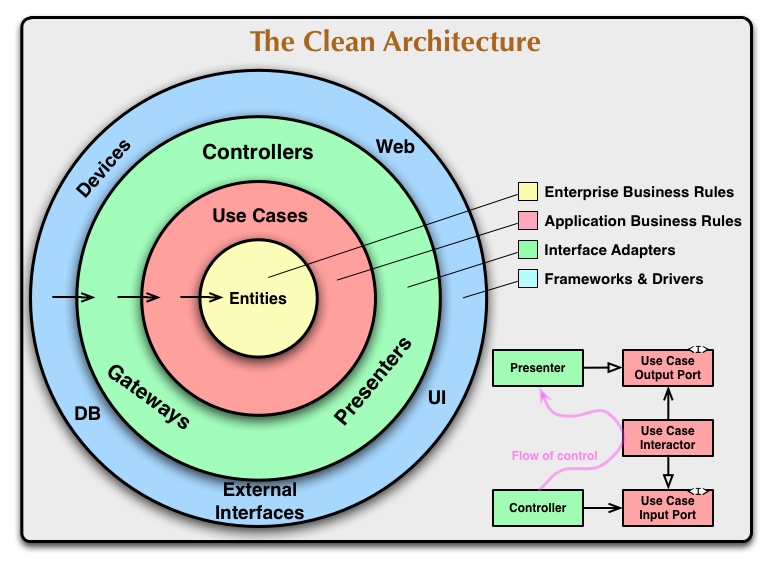

Clean Architecture UML Class Diagram

Bob Martin jumps from the high-level Clean Architecture diagram to this UML class diagram. I wish he had used the same terminology in both diagrams and been more explicit with the architecture boundaries in the UML Class Diagram so it would have been more obvious how these two diagrams relate to one another.

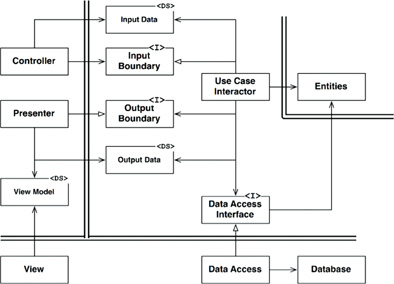

Hexagonal Architecture

Here is my Hexagonal Architecture diagram. It’s similar to Clean Architecture, yet different still.

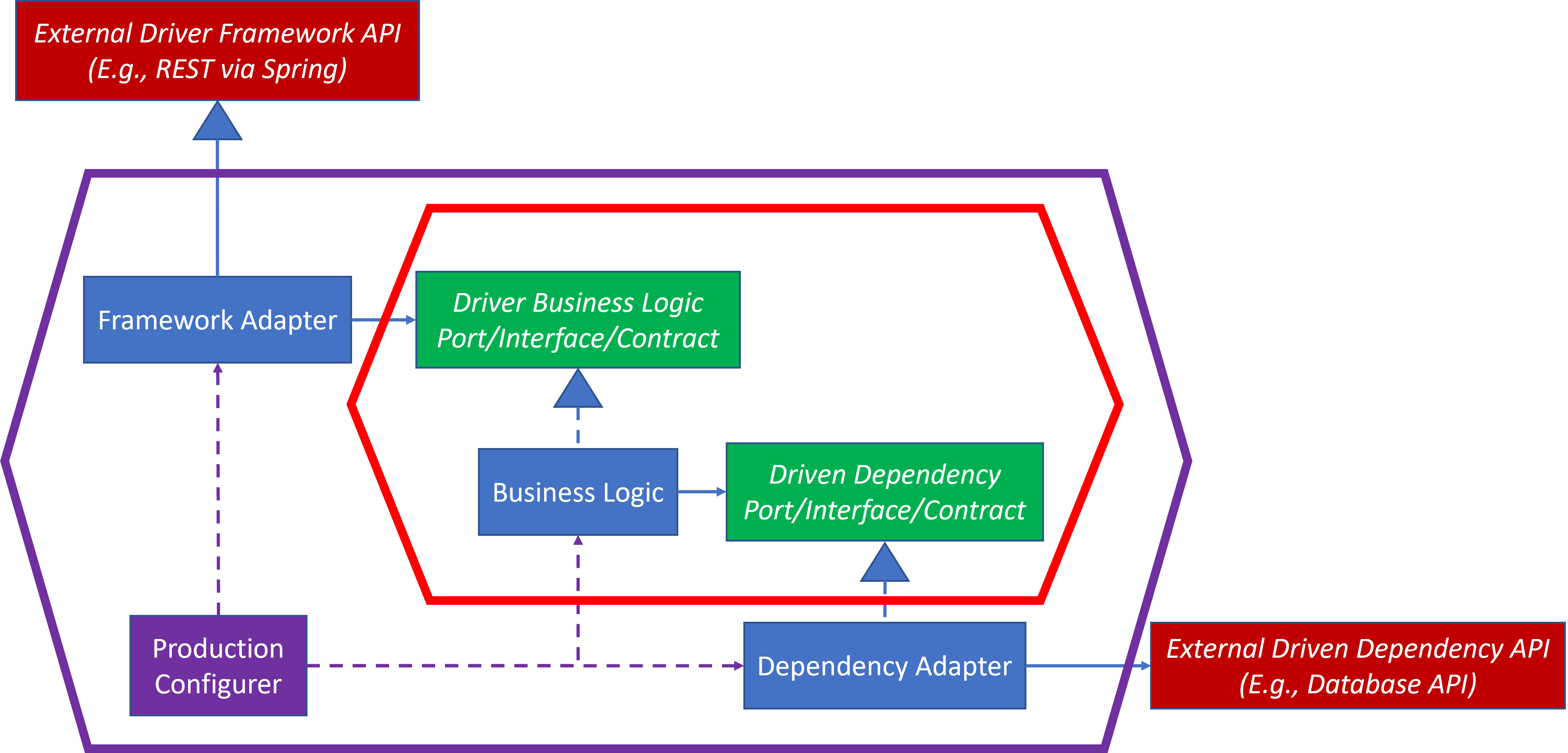

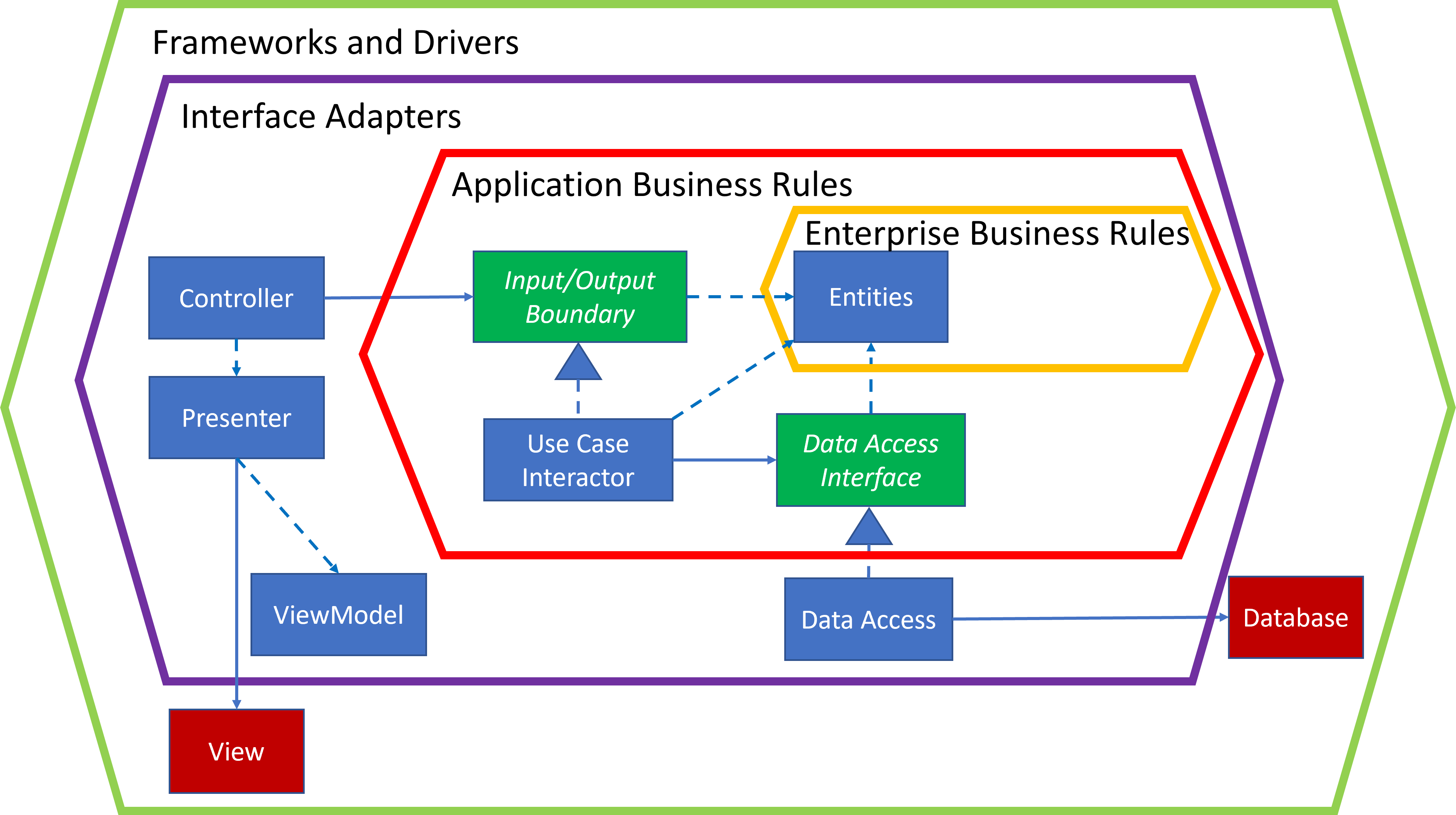

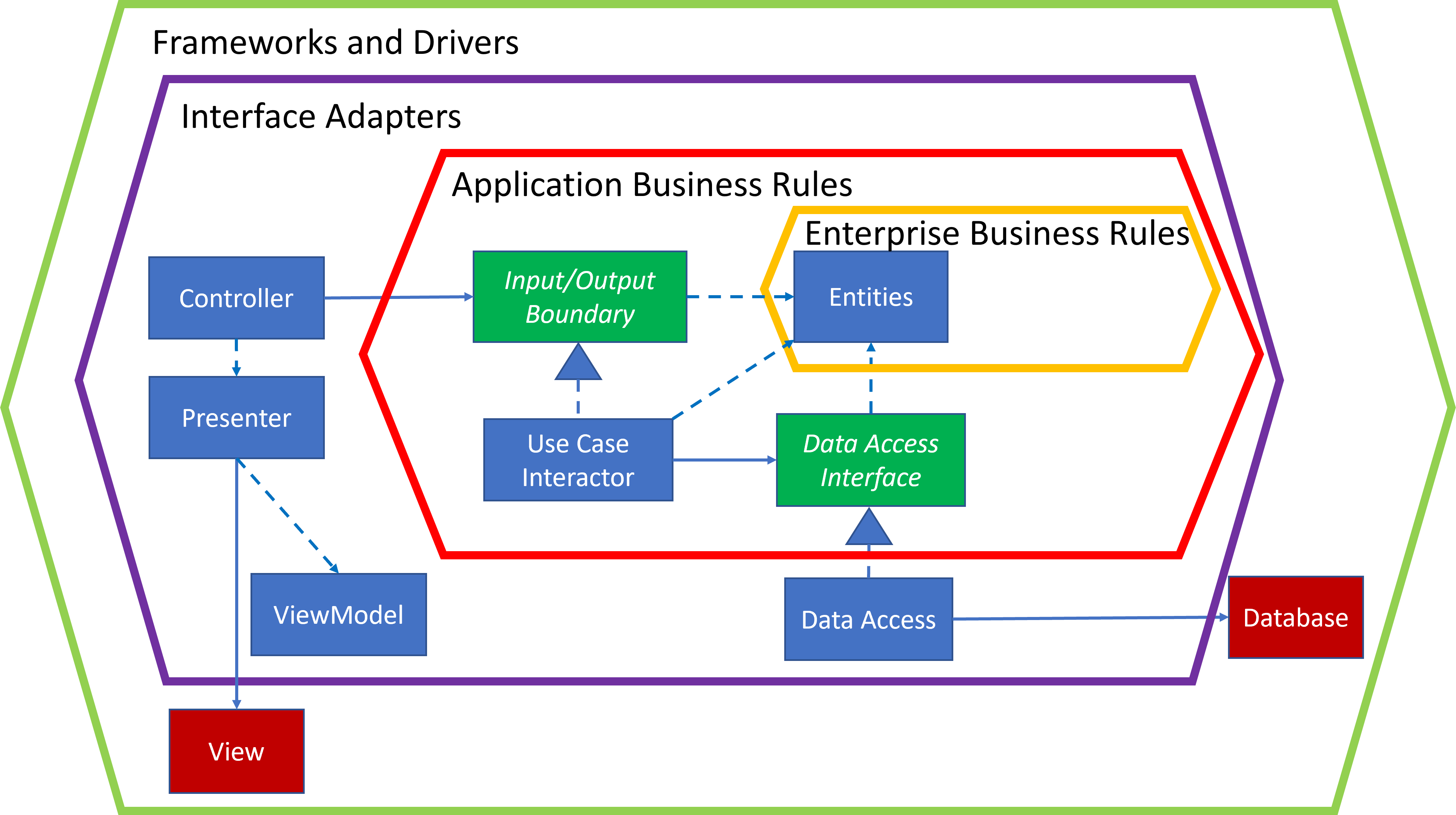

Three Into One

Here is my attempt to merge the elements of all three diagrams into one, so that hopefully it’s a bit more obvious how the elements relate to one another among the three separate diagrams.

Highlights:

- I’ve used hexagons rather than circles. The hexagon colors have no meaning. It’s just to make them easier to distinguish from one another. I’ve retained the red and purple hexagon colors from the previous Hexagonal Architecture diagrams as a bit of a style anchor.

- The four Inbound/Outbound Boundary interfaces and their Data Models in the Clean Architecture UML class diagram have been compressed into one Input/Output Boundary interface in the unified diagram.

- I’ve redrawn the Controller, Presenter, ViewModel and View slightly differently than in the Clean Architecture UML class diagram.

This is a lot of absorb. I’ll present each layer from the inside out in more detail. However, I also defer additional details to Bob Martin. He has written about this in his book and in blogs. His videos also provide more detail than I’ll provide here. Please refer to some of his references, which I’ll list in the Resources section at the bottom of this page, for more information. I can’t present it all here.

Enterprise Business Rules

I have not shown Entities in previous Hexagonal Architecture diagrams. If you look at Hexagonal Architecture Diagrams on the internet, you’ll see that Entities aren’t consistently represented, and even when they appear, they often have other names such as Domain Model.

Here is how Martin describes them in his Clean Architecture Blog:

Entities encapsulate Enterprise wide business rules. An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions. It doesn’t matter so long as the entities could be used by many different applications in the enterprise.

Entities are so domain specific that they transcend any specific feature of the system. I think they conceptually transcend the system too. These are domain rules that would exist, even if the system didn’t exist. They are critical to the business and universal. That is, these rules should apply regardless of the context in which they reside.

Here are several Entity examples:

- Customer

- Order

- Loan

- PhoneNumber

Since all relationship arrowheads point inward toward Entities, they are pure Stable/Fixed elements. They depend upon nothing else in the design.

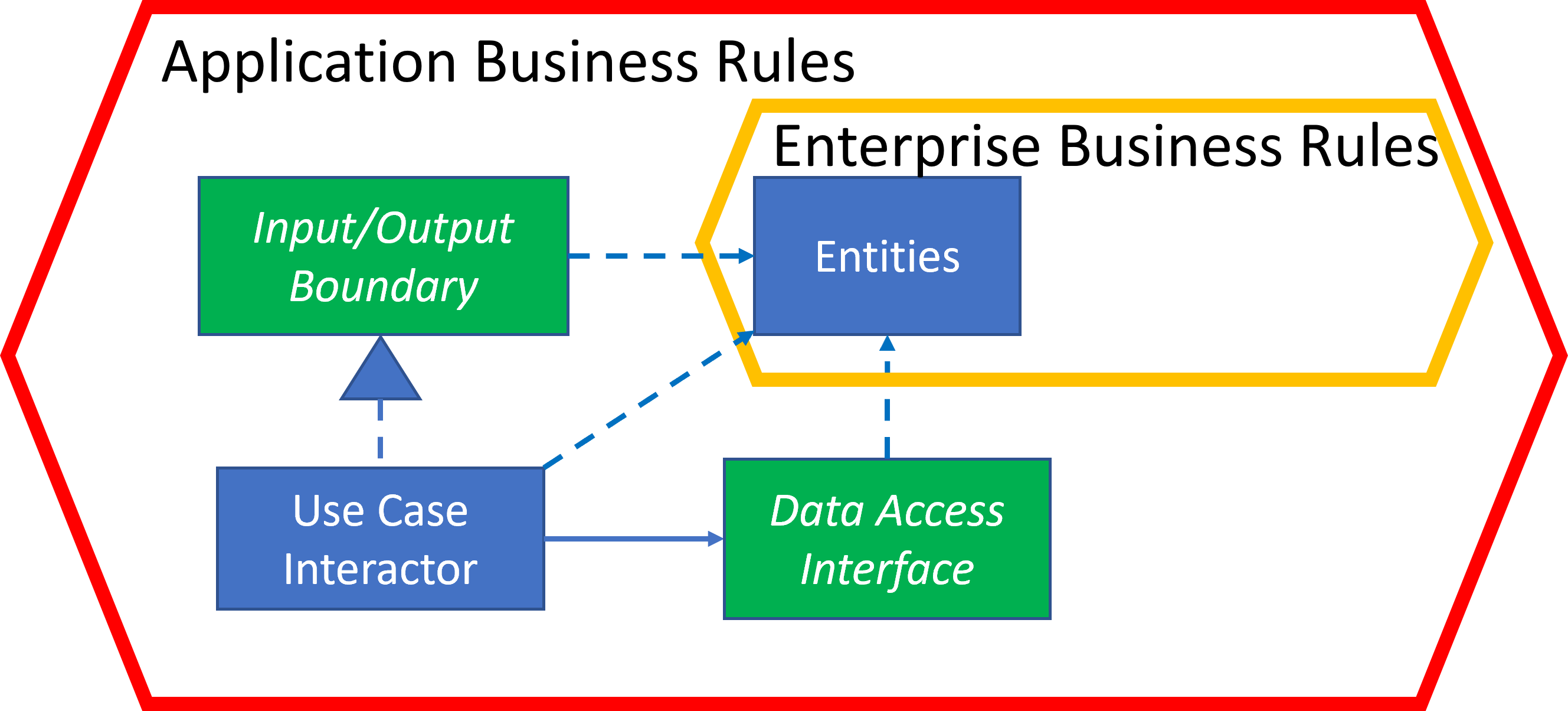

Application Business Rules

Application Business Rules add the next layer around the Enterprise Business Rules. All three types of elements in this layer can create and reference Entities.

Use Case Interactor

This is the Business Logic in the Hexagonal Architecture diagram. Hexagonal Architecture does not specify whether the Business Logic should be large grained or fine grained.

Clean Architecture favors fine grained, where Business Logic is scoped to the Use Case. Use Case is a UML concept. It is almost identical to a User Story. Interactor is another term for it. Martin uses the terms interchangeably.

Here are some examples of Use Cases:

- PlaceOrder

- CancelOrder

- WithdrawFunds

- BookReservation

Input/Output Boundary

The Input/Output Boundary aligns with the Driver Business Logic Port/Interface/Contract in the Hexagonal Architecture diagrams. Martin models this with four elements:

- Input Boundary, which is an interface that the Use Case implements.

- Input Model, which is a data object. I’ve also seen this listed as the Request Model. The Input Boundary is an interface, which declares methods. For me, the Input/Request Model represents the arguments for those methods.

- Output Boundary, which is an interface, which I think is passed as part of the Input Model to the Use Case. It was never quite clear to me.

- Output Model, which is a data object. It’s also listed as the Response Model. This is the information being returned from the Use Case.

Personally, I found this level of granularity without concrete examples a bit confusing. I think of a contract definition as an interface with a method like this:

interface UseCase {

ResponseModel execute(RequestModel requestModel);

}

For a more concrete example, the interface might look like the following:

interface PlaceOrder {

OrderPlacementDetails execute(Order order);

}

This interface defines the method to be executed to place an Order. Order would be a data class, which could contain information such as:

- Customer

- ItemNumber

- Quantity

- DiscountOptions

The OrderPlacementDetails is a response data class, which could contain information such as:

- TrackingInformation

- EstimatedDeliveryDate

These bulleted items would probably be Entities. I prefer a name more along the lines of Domain Business Objects, since these tend to be domain concepts. I prefer domain element types over primitive types, such as int, String, etc. This is a topic for another blog entry (TBD), so I won’t go into full detail here. But here’s a quick summary. I prefer to keep primitive types out of interface contracts unless the contract element is truly a primitive type within the domain. I’ve seen too many methods that use primitive types when they should have considered the domain concept. There’s even a code smell using too many primitive types: Primitive Obsession:

Data Access Interface

The Data Access Interface aligns with the Driven Dependency Port/Interface/Contract in the Hexagonal Architecture diagrams. Other than different names, the concept is identical.

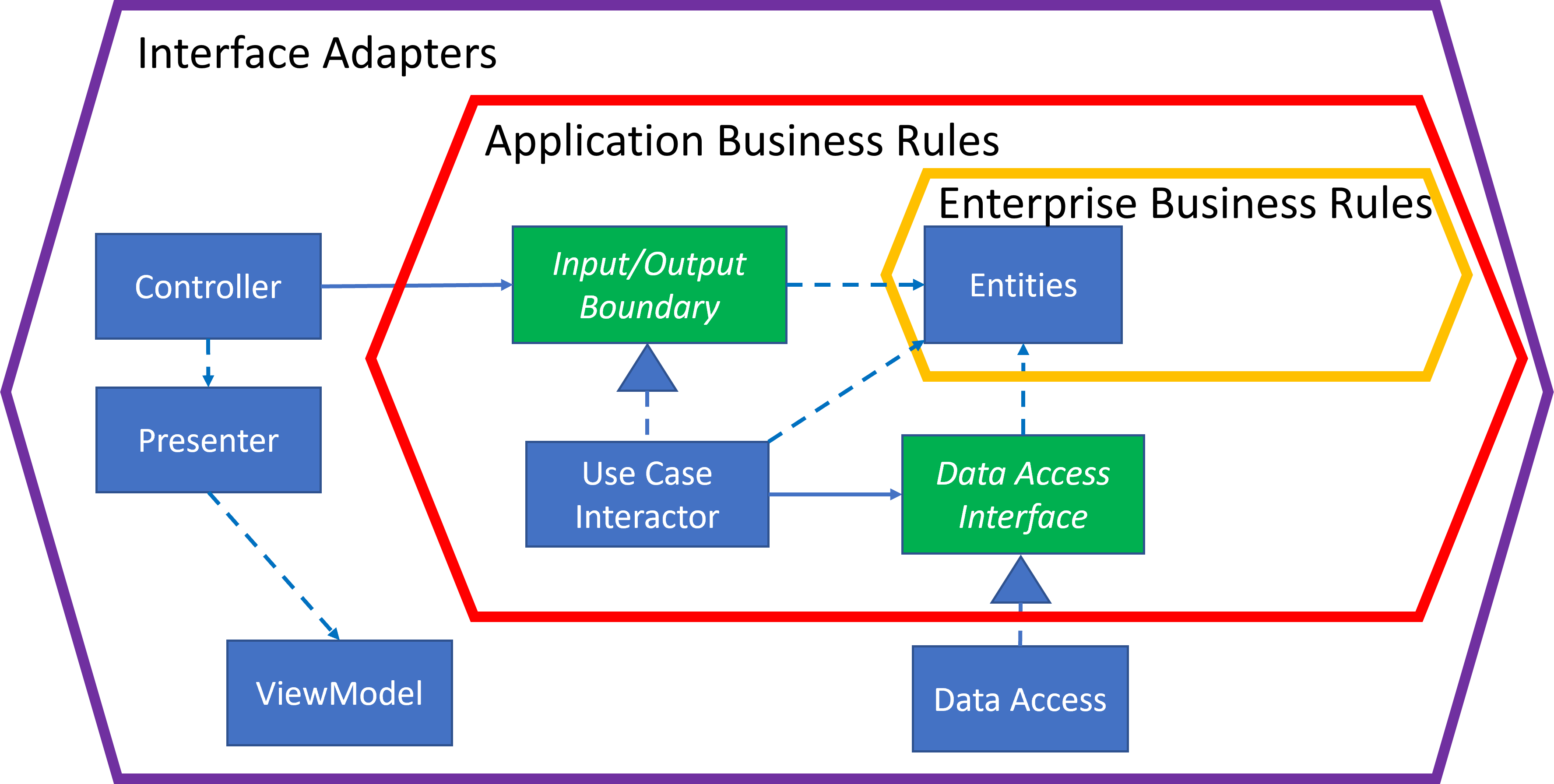

Interface Adapters

Interface Adapters add the next layer around Application Business Rules. Some of my classes are designed differently than what Bob Martin provided in his UML class diagram.

Controller

The Controller aligns with the Framework Adapter in the Hexagonal Architecture diagram. This is a Driver element where a request or inbound message will first be encountered.

The Controller is an Adapter. The Controller adapts the types of the inbound message, which may be basic types, into Entity/Domain types so that the processing can continue via the Input/Output Boundary interface.

Presenter and ViewModel

These were among the most confusing parts of the Clean Architecture design for me. I recommend reading Martin’s content and viewing his video presentations. But here’s a quick primer.

The Output/Response Model is returned by the Input/Output Boundary interfaces has no presentation context. It’s usually going to be comprised of domain business objects, such as Entities.

While the Controller could take upon complete responsibility to make the data presentable to the end user, Martin suggests using a Presenter. This is another class that the Controller would delegate to.

The Presenter will accept the Output/Response Model and build a ViewModel based upon it. The ViewModel contains all the content that resides in the Output/Response Model, but the ViewModel content is formatted so that it’s presentable to the user. For example, if the user is using a web browser, then the ViewModel might be an HTML file, whereas the Output/Response Model should have no trace of HTML.

Different types of Presenters might be needed depending upon how the user might be consuming the information.

Data Access

The Data Access aligns with the Dependency Adapter in the Hexagonal Architecture diagram. Other than different names, the concept is identical.

Frameworks and Drivers

And now we’re back to where we started with the merged diagram.

Frameworks and Drivers is the layer around the Interface Adapters. It is not a separate layer in the Hexagonal Architecture diagram. In Hexagonal Architecture it’s represented as all External Dependencies beyond the purple hexagon.

The dependency arrows point outward in my rendition. This is why I think Martin’s arrow is incorrect in the High-Level UML class diagram. I think that since Adapters have dependencies upon and knowledge of external elements then arrows should point outward, not inward. Look at Martin’s UML class diagram, and his arrow is pointing to the Database. The direction of the arrowheads between his two diagrams is inconsistent.

Controller

The Controller is not in this layer, but I’d like to revisit it once more. In Martin’s UML class diagram, the Controller just floats in the Interface Adapter layer. I think it should be associated with something in the Framework layer, such as extending a Framework, which is how I render it in my Hexagonal Architecture diagrams.

View

This is the mechanism that renders the ViewModel. For example, the View could be a web browser which is rendering an HTML ViewModel file.

Martin draws the View pointing inward depending upon the ViewModel, and in a sense it does depend upon it, but only for the content. I point the arrowhead outward, since the View has no knowledge of the ViewModel or how it’s created. In my version of this design, the Presenter creates the ViewModel with content and passes it to the View as an argument so that it can be rendered. In other words, the View is external, and it renders what’s given to it. It doesn’t depend upon or have knowledge of the ViewModel, until the ViewModel is passed to it as an argument.

Database

The Database is any typical database. In most cases, it will be supplied by an external vendor.

What’s Missing?

There is no Configurer. Martin didn’t include one in his diagram, so I didn’t attempt to show one either. However, he has indirectly referred to concepts consistent with Configurers. A glimpse of this is visible in Factories/Abstract Factories. Martin often refers to concrete class creation as being the lowest and “dirtiest” part of the code, often residing in main(). For more details on how I approach the Configurer, see Dependency Injection

If I were to have added a Configurer in the diagram, it would still be in the Interface Adapter layer and it would create Data Access, Use Case/Interactor and Controller as I had shown in the Hexagonal Architecture diagram.

Data Type Consistency

Entities reside in the deepest core of this design. Their management is the central focus of most software. We want to ensure that our software manages its Customers, Orders, Loans, PhoneNumbers, etc. correctly.

However, our Frameworks and Drivers don’t have knowledge of or depend upon the Entities. You can’t save a Customer Entity in a database. You can store a representation of a Customer Entity by creating a database table for Customers, which have Customer related fields, such as CustomerId, CustomerName, CustomerAddress, etc. Likewise, a Customer Entity won’t be in the REST API, but Customer related fields will be there.

While the Customer fields in the REST API and those in the database table will be similar, they may not be the same in name and possibly even form.

Driver and Driven Adapters will have knowledge of the REST API definitions and database definitions respectively as well as knowledge of Entities. They will translate between Entities and data representations. If a new External Framework/Dependency is added, and it has yet another way to data representation for a Customer, then a new Adapter for that Framework/Dependency will manage that translation as well.

Leaky Abstraction

Ports/Interfaces/Contracts will convey intent, but they should avoid External Framework/Dependency details. We must be careful not to let External Framework/Dependency details leak through the Adapters. For example, if a database operation fails, it may return an error code that’s specific to the database vendor. That specific error should not be leaked by the Adapter up through interface. If a detail like this is passed up in the Business Logic/Use Case/Interactor, then that’s known as a Leaky Abstraction. All abstractions leak to some degree, but we want to keep it to a minimum.

The Adapter can indicate through the interface that there was an error and possibly even the nature of the error, if the error makes sense within the context of the interface contract. For example, the interface contract’s intent could be persistence without an indication of the persistence vendor or mechanism. If the database fails to save a record, then the Adapter could translate the database specific error into an interface error along the lines of: UnableToPersistException. The specific database error should be logged, since we still want to retain that information for diagnosis.

Likewise, if the Adapter delegates to an RESTful internet call, then it should not leak HTTP status codes back up through the Port/Interface/Contract that they implement. However, they can convey a status indicating some form of status that’s independent of HTTP status codes.

The same applies to the Framework Adapters too. Specifics on the Driver side should not leak through the Business Logic Interface into the Business Logic.

Keeping leaks out of abstractions can be tricky, since it’s not always clear whether the intent is an abstraction or influenced by the external dependency. This is why it’s wise to focus upon the Port/Interface/Contract definitions before considering what the external dependencies might be.

Summary

Hexagonal Architecture and Clean Architecture have the same basic intents, but each presents it in slightly different ways. Hexagonal Architecture focuses upon structure. Clean Architecture focuses upon the semantics of the structure.

References

There are many online resources with diagrams and implementations in different programming languages. Here are some free resources:

- Screaming Architecture blog by Bob Martin

- The Clean Architecture blog by Bob Martin. Excellent summary.

- Summary of book “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin summary on GitHub managed by Yannick Grenzinger

- Clean architecture for the rest of us blog by Suragch.

- Clean Architecture Linkedin blog by Reza Bazghaleh

- Bob Martin as a roughly 1-hour presentation about Clean Architecture, which is available from various conferences. Here are links to several in reverse chronological order. They are all similar, but there are variations (NOTE: Martin likes to start his presentations with a ~10-minute science lesson, and he’s a slow talker. I tend to jump ahead to the actual software portion of his presentation and play at a faster than normal speed):

- ITkonekt 2019 Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), Clean Architecture and Design - June 10, 2019

- The Principles of Clean Architecture by Uncle Bob Martin - Norfolk Developers, December 15, 2015

- Robert C. Martin - Clean Architecture and Design - Norwegian Developers Conference 2014, June 4, 2014

- Robert C Martin - Clean Architecture and Design - Norwegian Developers Conference 2013, June 4, 2014

- Robert C Martin - Clean Architecture - Norwegian Developers Conference 2012, June 4, 2014

- Robert C Martin(Uncle Bob) -Clean Architecture and Design-2012 COHAA The Path to Agility Conference COHAA, October 25, 2012

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

- Clean Architecture, the book by Bob Martin (Amazon and O’Reilly)

- Architecture, Use Cases, and High Level Design, the video by Bob Martin (Clean Coders and O’Reilly)

See previous blog References.