Hexagonal Architecture – Why it works

It’s all about dependency and knowledge management

Introduction

This continues the Hexagonal Architecture series with the structure of Hexagonal Architectures, and why I feel that the Hexagonal Architecture design works so well.

I feel that Hexagonal Architecture design works well because of how it manages dependency and knowledge relationships. This dependency and knowledge management epiphany came to me while reading Chapter 14: Component Coupling in Clean Architecture by Bob Martin and watching his CleanCoders Component Coupling video on O’Reilly.

Martin was mostly addressing component dependencies and their implications with deployment. I realized the same principles apply to classes and their implications with design stability.

The Theory

Don’t Panic! There isn’t much theory. This is mostly going to be a few straightforward definitions, implications, and principles.

Definitions

Bob Martin separates his dependency principles in two parts: class dependency via SOLID principles and component dependency. I think there’s value in applying the component dependencies to classes as well. We can think of a class as a component with one element in it.

Software elements, such as classes or interfaces, are rarely insular within a design. Software elements have relationships with other software elements.

These are not equitable relationships. These are not relationships of elements working together and supporting each other. Software element relationships are one-way. Only one element depends upon and has knowledge of the other. The element being depended upon has no dependency or knowledge the element depending upon it. It doesn’t even know it’s in a relationship.

Software element relationships are more like one-way streets.

When A depends upon B, then A has knowledge of B. But B has no dependency upon or knowledge of A. B doesn’t even know that it’s in a relationship with A. A reaps the benefit of its relationship with B by inheriting B’s behaviors or delegating to B. But A is taking all the risk too. If B changes, it could cause A to change as well. If A changes, B won’t care.

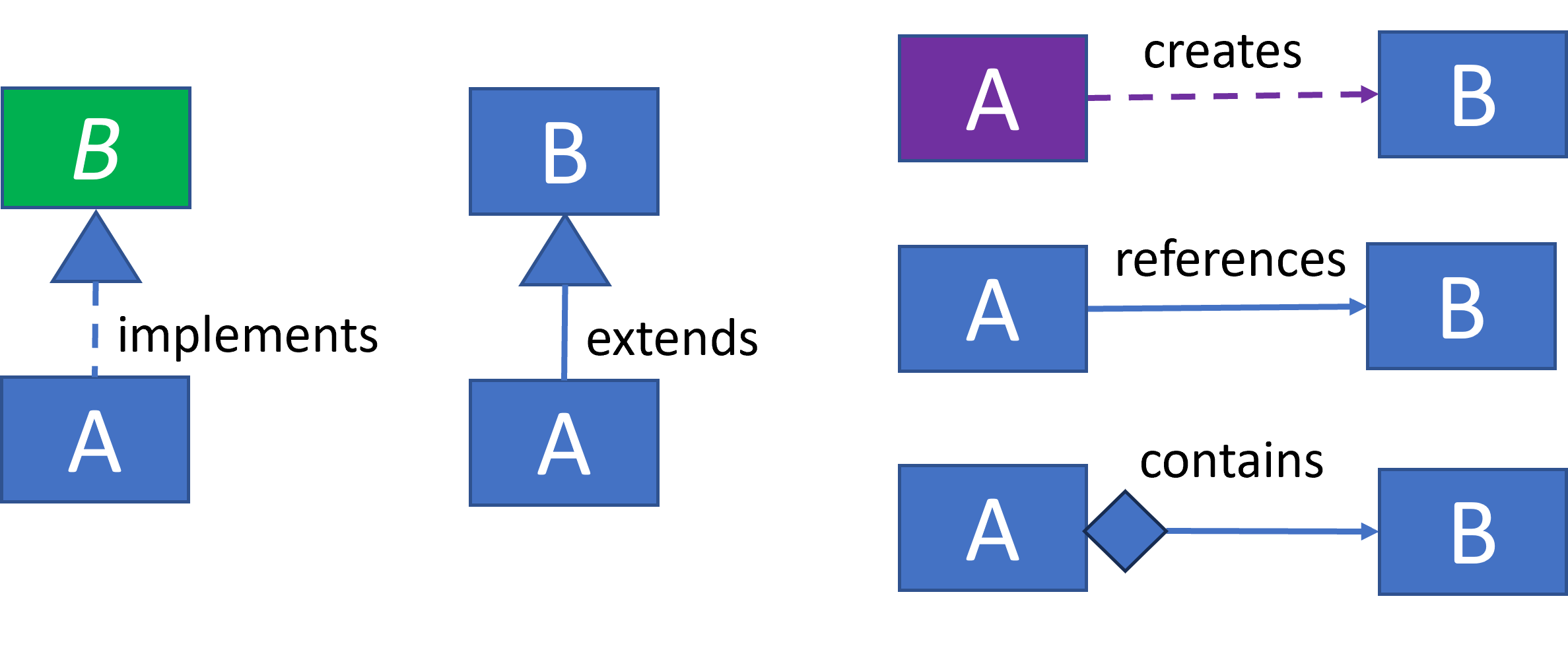

Let’s put this into some concrete “Java” terms, A depends upon and has knowledge of B, when:

- A implements B

- A extends B

- A creates an instance of B

- A references B as:

- a field attribute

- a local variable

- a parameter argument

- a collection

We can see these relationships in UML class diagrams via the lines that connect the elements. And the direction of the dependencies is in almost all cases represented by an arrowhead on that line. The Composite/Aggregation relationship doesn’t traditionally indicate dependency with the arrowhead, but it can be added easily.

Implications

Dependency and knowledge exist between pairs of software elements. The direction of dependency and knowledge is in one direction. UML class diagrams indicate dependency and knowledge direction via an arrowhead.

Therefore, we can use UML class diagrams as a visual means to identify and trace dependency and knowledge within a design and its implications. A UML class diagram is a Directional Graph where the software elements are the nodes and the dependency/knowledge relationships are the edges.

The Acyclic Dependencies Principle

Martin’s first design principle is to remove cycles. That is, not only is the graph representation of a UML class diagram a Directed Graph, but it should be a Directed Acyclic Graph.

When a design contains a cycle, then consider Dependency Inversion Principle to break it.

The Stable Dependencies Principle

Bob Martin’s dependency/knowledge analysis is based upon the number of inward arrowhead relationships versus the number of outward arrowhead relationships for a software element.

Stable or Fixed Design Elements

Classes with more inward arrowhead relationships than outward arrowhead relationships are mostly immune to updates in the design. They are much like B in the UML examples listed above.

Martin’s term for these elements is Stable. I prefer the term Fixed. They are Stable in that they are unlikely to change.

Strings, LinkedLists and other utility classes are Stable. They are so ubiquitous that no one would dream of making a non-backwardly compatible change to them. These are classes with well-defined narrowly scoped behaviors that don’t change and usually have no business specific context. Strings, LinkedLists and other utilities classes have thousands if not millions of inward arrowhead relationships if we could count them. On the other hand, they have very few outward arrowhead relationships.

We all feel comfortable using and depending upon these utilities, since we know their behavior won’t change and rip the rug out from underneath our design.

Our design will also have our own business domain elements that tend to be Stable and Fixed as well.

Unstable or Flexible Design Elements

Classes with more outward arrowhead relationships than inward arrowheads relationships are mostly invisible to other elements in the design. They are much like A in the UML examples listed above.

Martin’s term for these elements is Unstable. I prefer the term Flexible. They are Flexible in that they can change without a major impact upon the rest of the elements in the design.

Adults Versus Teenagers

Martin has referred to Stable/Fixed elements as adults and Unstable/Flexible elements as teenagers.

Stable/Fixed components are adults. They don’t tend to depend upon other components, but other components depend upon them. The more dependency an adult component has, the more Fixed and Stable it needs to be. That’s because a change to it may have disaster effects upon the rest of the design.

Unstable/Flexible components are teenagers. They depend upon other components, but other components don’t depend upon them. They can change at a moment’s notice.

The Stable Dependencies Principle Summary

Given the definitions above, the Stable Dependencies Principle basically states that dependency/knowledge should flow in the direction toward stability.

That is, design elements should depend upon design elements that are at least as Stable as they are. You don’t want Stable/Fixed elements to depend upon Unstable/Flexible ones. That would be like building a tower too top heavy and prone to collapse.

We need both Stable/Fixed and Unstable/Flexible elements in our design. Too many Stable/Fixed elements and the design is too rigid. Too many Unstable/Flexible elements and the design has no organization or structure.

The Stable Abstractions Principle

The Stable Abstractions Principle is a consequence of the Stable Dependencies Principle. Unstable/Flexible design elements tend to be concrete, whereas Stable/Fixed design elements tend to be abstractions.

Therefore, as we follow the flow of dependencies and knowledge in a good design that adheres to the Stable Dependencies Principle, we’ll tend to see the flow start with concrete classes move through classes of increasing stability and end with abstractions.

We’ll see examples of all these principles with the Hexagonal Architecture design.

Implication Summary

The dependency/knowledge principles summarize as:

- Remove dependency cycles.

- Stable/Fixed elements should be those elements that don’t change often.

- Unstable/Flexible elements should be those elements that may need to change often.

- Good designs need both Stable/Fixed and Unstable/Flexible elements.

- Unstable/Flexible elements should depend upon more Stable/Fixed elements.

- Dependency will flow from Unstable/Flexible concreteness toward Stable/Fixed abstraction.

Application of the Theory and Implications to Hexagonal Architecture

Let’s consider how these principles apply with Hexagonal Architectures.

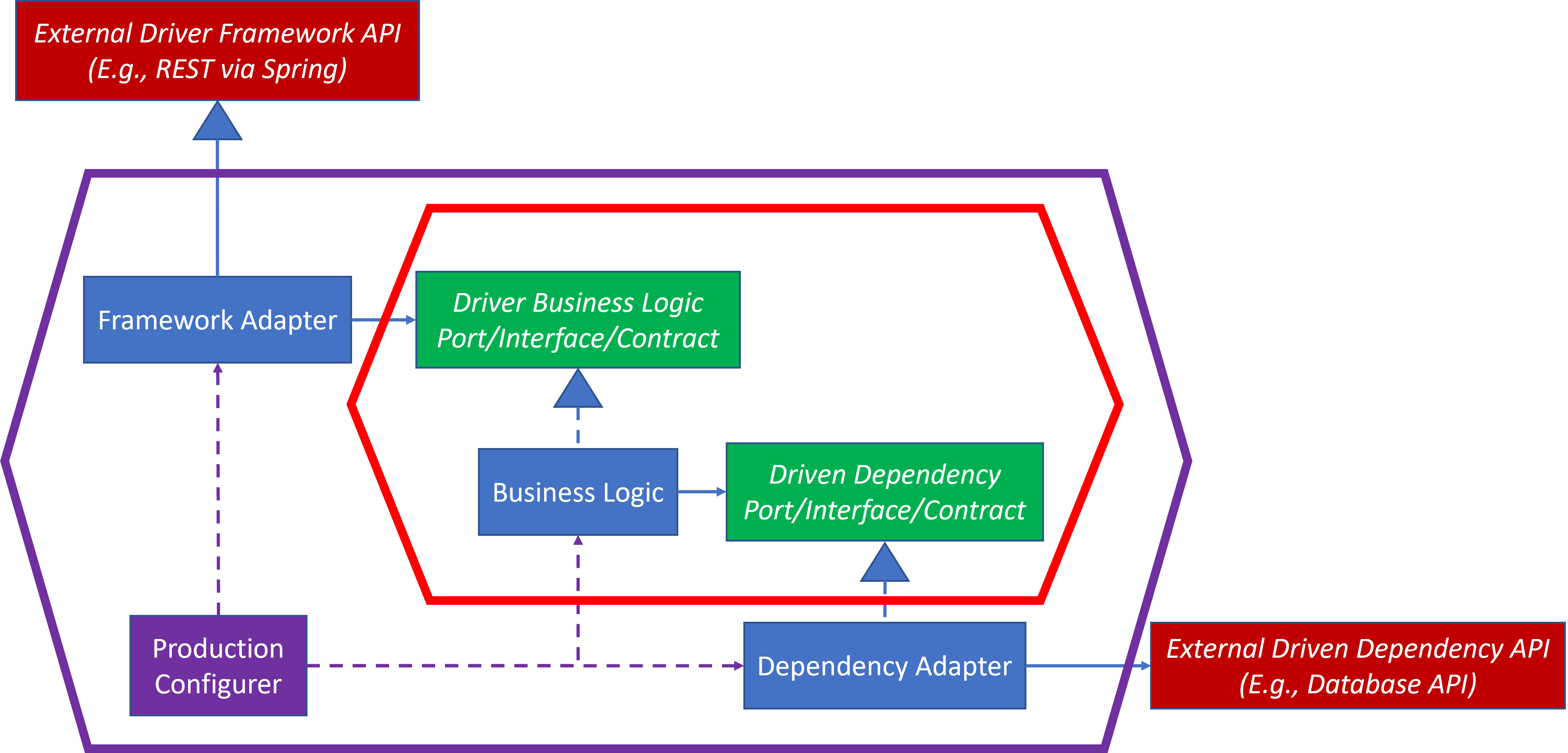

Cycles

There are no dependency/knowledge cycles. Start at any rectangle in the above diagram and follow any set of directed paths. You can never return to your starting position.

Ports/Interfaces/Contracts

The Port/Interface/Contract elements are pure Stable/Fixed elements. All arrows are inward. They have no dependencies nor knowledge of other elements. Interfaces tend to only contain Contract definitions. They traditionally don’t contain code. Once defined they don’t tend to change often. They have zero knowledge of the rest of the design. They don’t even know that the rest of the design exists.

Adapters and Façades

Adapters and Façades are Unstable/Flexible. Their only inward relationship is their creation. Adapters and Façades can be swapped out with ease.

Adapter responsibility is limited to implementing their Contract dependency and delegating it to an External Dependency API. While it may require developer blood, sweat and tears to understand the External Dependency API, the Adapter implementation is only concerned with the translation between the Contract and the External Dependency API. The implementation should be relatively straightforward once the External Dependency APIs are understood.

The Contract may require behavior that’s not provided by a single External Dependency API. A Façade manages the transition to multiple External Dependency APIs. Since it has more External Dependencies, Façades will be more likely to change than an Adapter. It will have a larger implementation, but Façades should still not contain any business logic implementations.

Business Logic

Business Logic is Unstable/Flexible, which is sort of surprising. The Business Logic is the main reason for the entire design, and it is mostly invisible! Like Adapters, the only Business Logic inward relationship is its creation. Since the Business Logic is Unstable/Flexible, it can be updated or even replaced without any impact upon the rest of the design.

Configurers

Configurers are pure Unstable/Flexible elements. Nothing depends upon them. Nothing knows about them. They are completely invisible to the rest of the design. Their only responsibility is to create objects in the design and assemble them.

Configurers only depend upon concrete class constructors and their signatures. Most concrete class updates won’t affect Configurers. Configurers tend to be relatively small. When updates are required, their updates (or complete replacement!) tend to be straightforward.

Configurers are not only invisible to the rest of the design, but they are also invisible to each other. The Hexagonal Architecture design can accommodate as many Configurers as needed. The design can easily swap out Configuers for different environments, such as Production, Test, etc.

Hexagons

Hexagons are a design element. They do not appear in the implementation. They are boundary constraints, which constrain the direction of dependency and knowledge. They are like the borders between countries, which determines who may cross the border. Laws and rules may be different on different sides of the border too.

Red Hexagon

The Red Hexagon defines a pure Stable/Fixed boundary. All dependencies and knowledge point inward. The components within the Red Hexagon have no dependencies or knowledge of any other parts of the design.

Purple Hexagon

The Purple Pexagon encapsulates the entire design. All arrows point outward from it. This means that the entire design is a pure Unstable/Flexible boundary.

External Dependencies mostly don’t know that the behavior within the Purple Hexagon exists. Frameworks may know that an Adapter has registered within it. Databases may have schema information about the domain.

Zone Between the Purple and Red Hexagons

The elements between the Red and Purple Hexagons contain Adapters/Façades and Configurers. They are Unstable/Flexible. They can be changed easily, which allows the Business Logic within the Red Hexagon to operate in just about any environment of External Dependencies imaginable.

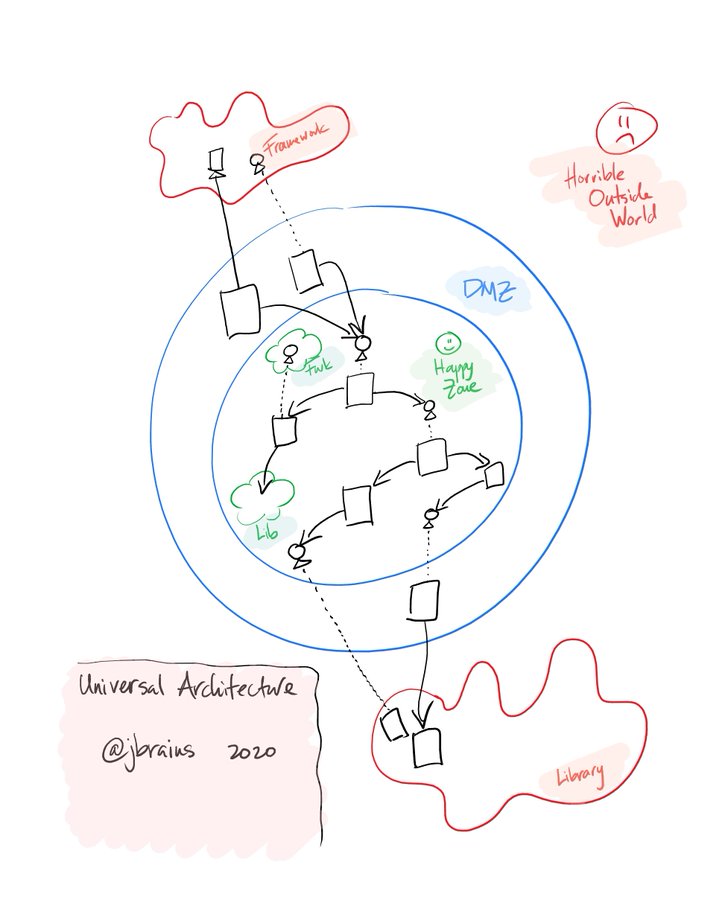

This zone is like the DMZ as shown by J. B. Rainsberger in this Universal Architecture Tweet.

Event Horizons

My use of Event Horizon is inspired by Black Holes, but the metaphor is not exactly the same behavior as an event horizon for a black hole.

I’m using the term as a metaphor that information cannot cross a boundary. Once mass or information crosses the event horizon of a black hole, it is no longer available to an observer beyond the event horizon. As for what happens to the mass or data on the other side of the event horizon, we, or at least I, do not know.

I used the adjective pure a few places above. By that I meant that the element had all inward arrowheads or all outward arrowheads. Let’s consider how the concept of an Event Horizon applies to pure Unstable/Flexible elements and pure Stable/Fixed elements.

Pure Stable/Fixed Elements

Pure Stable/Fixed elements are those with only inward arrowhead relationships. They include:

- The Port/Interface/Contract

- The Red Hexagon Boundary

Pure Stable/Fixed element behavior is like flipped Event Horizon behavior. Any element has the ability to depend upon and have knowledge of the Port/Interface/Contract and the Red Hexagon Boundary, which is really the collection of Ports/Interfaces/Contracts. Pure Stable/Fixed elements and boundaries have no dependency or knowledge beyond their own boundaries. While other elements in the design know of them, Pure Stable/Fixed elements have no knowledge of the other elements of the design. Pure Stable/Fixed elements don’t even know that they are part of a design.

Pure Unstable/Flexible Elements

Pure Unstable/Flexible elements are those with only outward arrowhead relationships. They include:

- The Configurer

- The Purple Hexagon Boundary

Pure Unstable/Flexible element behavior is more like Event Horizon behavior. No element has the ability to depend upon or have knowledge of Configurers or the Purple Hexagonal Boundary. Pure Unstable/Flexible elements and boundaries have dependency and knowledge beyond their own boundaries, but the other elements have no knowledge of them. The other elements don’t know if pure Unstable/Flexible elements are implemented as one class or a thousand. The other elements of the design don’t even know that Pure Unstable/Flexible elements are part of their design.

Business Logic and Adapters/Façades are technically not pure; however, they are only known by the Configurer, which is pure. If one were to draw a boundary around the Configurer, Business Logic and Adapters/Façades, then that boundary would be Pure Unstable/Flexible, and it would exhibit all of the behaviors listed in the paragraph above.

Class-to-Class Dependencies … There Are None

The concrete classes have no dependencies or knowledge of any other concrete classes in the design. The Business Logic and the Adapters don’t know that the others exist. It’s only the Configurer that knows them all.

The Business Logic and Adapters are separated via the Port/Interface/Contract elements. All arrows point inward into the Ports/Interfaces/Contracts. Nothing points outward to the Business Logic and Adapters. Therefore, you can’t start in one concrete class and find a directed path to another concrete class. We cannot cross the Event Horizon of the Port/Interface/Contract elements, and hence hop over and depend upon or have knowledge of the other concrete classes.

Once a Port/Interface/Contract starts to stabilize, then the concrete classes that depend upon it can proceed with their implementation in parallel by different developers or teams without stepping upon each other’s toes.

The only concrete classes that know about other concrete classes are Configurers, and their level of knowledge is restricted to creation. And depend upon whether Factories are used in Configurers, they may not even contain concrete class knowledge.

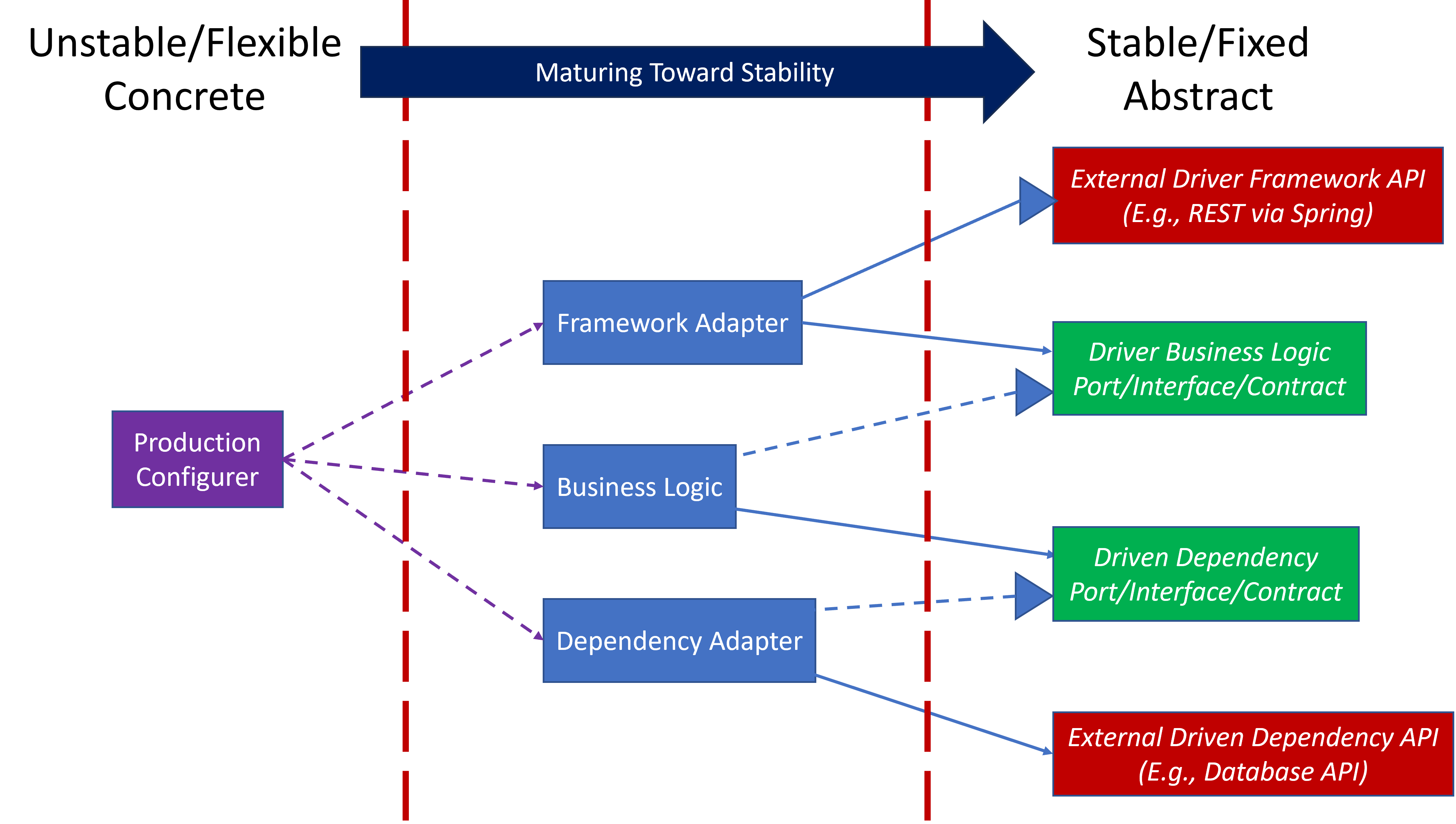

Topological Sorting

Let’s redraw the Hexagonal Architecture design using Topological Sorting and without the hexagons. That is, represent the flow from the design elements based upon their dependencies from concreteness to abstraction.

This representation reenforces how well the Hexagonal Architecture design adheres to Bob Martin’s:

- Acyclic Dependencies Principle – There are no cycles.

- Stable Dependencies Principle – Elements depend upon more Stable elements.

- Stable Abstractions Principle – The flow is from concrete elements to abstractions.

Summary

I feel that Hexagonal Architecture works well because it adheres to these dependency and knowledge principles. Here’s a summary of how Hexagonal Architectures leverages these principles to its benefit:

- The Business Logic implementation is cocooned from its environment, so that it can execute without updates in almost any environment with the support of Adapters/Façades and Configurers.

- The Business Logic, Adapter/Façade and Configurer implementation may consist of any number of classes without any overall implications upon the rest of the design, because they are Unstable/Flexibie elements with an Event Horizon that hides all details.

- The Business Logic and Adapters/Façades are separated via Ports/Interfaces/Contracts. Therefore, an update in one implementation class won’t affect the other implementation classes.

- Once Port/Interface/Contract methods stabilize, development may progress in their corresponding Business Logic, Adapter/Façade implementations in parallel, even by different developers or teams.

This adherence to dependency and knowledge principles isn’t restricted to Hexagonal Architecture. Design Patterns tend to adhere to these principles as well. Once I realized this, I had a whole new appreciation for why the design patterns work. Keep these principles in mind when I return to design patterns in future blog posts.

References

I mentioned Bob Martin’s Component Coupling materials in the Introduction. Unfortunately, I can no longer find his Component Coupling video on O’Reilly, so I can’t provide an O’Reilly video reference here, but I can provide other references:

- O’Reilly Resource: Clean Architecture _Chapter 14: Component Coupling - Requires an O’Reilly account

- Amazon Resource CleanArchitecture - Book available for purchase.

- CleanCoders Component Coupling: Episode 17 - Video available for purchase. I believe this was the video I watched on O’Reilly years ago.

- Principles of Component Coupling - A blog, which covers what Martin covers in his book and video.

- The Principles of OOD - A blog by Bob Martin.

- Clean Architecture – How to Quantify Component Coupling - Landing page for the CodingBlocks.net podcast where they covered Component Coupling.

See previous blog References.