Test Layers; From Unit to System

Building Confidence with the Right Tests at the Right Level

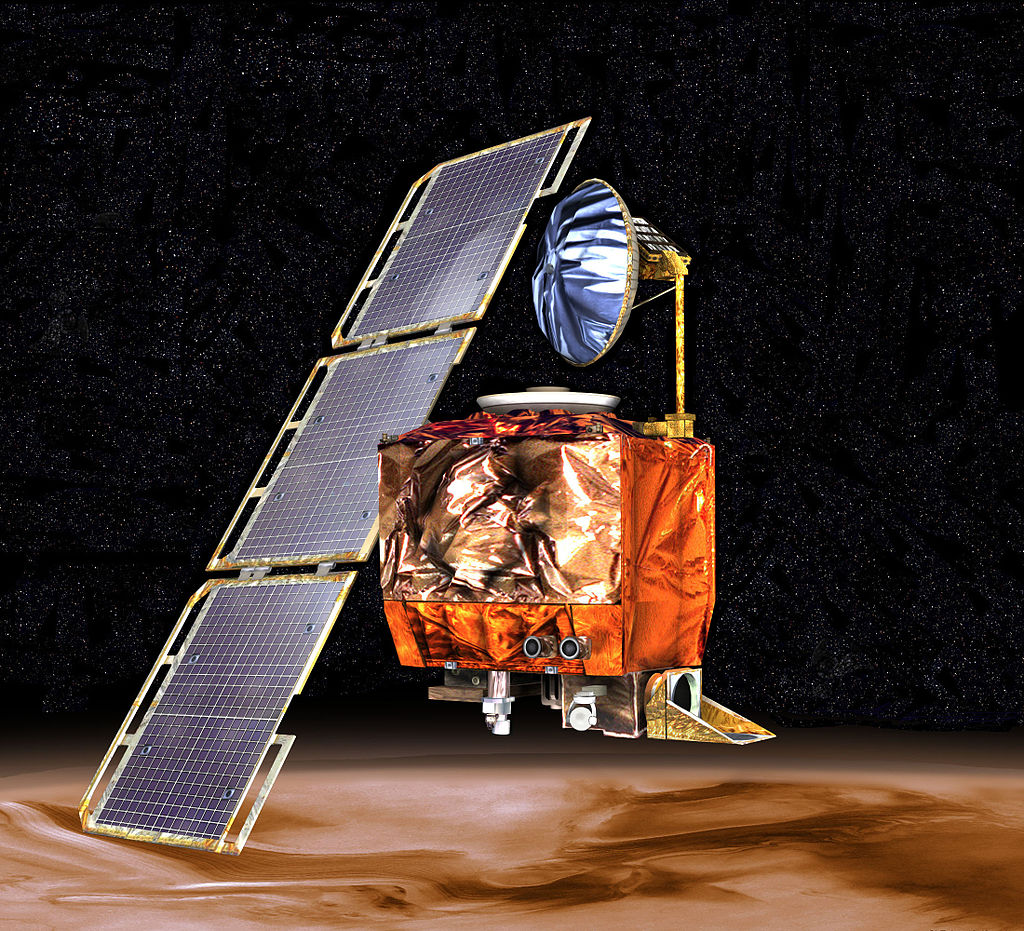

A Lesson from Mars: When Testing Breaks Down

On September 23, 1999 NASA lost contact the Mars Climate Orbiter as it was establishing its orbit around Mars. The cause of failure was Lockheed Martin’s ground control software using the imperial measuring system; whereas, NASA’s orbital software was using the metric measuring system. Ground control was sending thruster firing instructions as pound-force seconds, but the orbiter was expecting them as newton-seconds.

This failure cost 286 days of mission time and $327.6 million.

The discrepancy had previously been noticed, but the warning was not heeded:

The discrepancy between calculated and measured position, resulting in the discrepancy between desired and actual orbit insertion altitude, had been noticed earlier by at least two navigators, whose concerns were dismissed because they “did not follow the rules about filling out [the] form to document their concerns”.

Though this seems like a simple measurement mismatch, at its root it was a contract verification failure—a failure to validate shared expectations between two systems. This is exactly the kind of failure that well-layered software testing can help uncover.

Whether you’re a junior developer just beginning to explore automated testing or a senior engineer refining your team’s quality strategy, understanding layered tests can help avoid the kind of systemic failures seen in stories like the Mars Climate Orbiter.

My Automated Test Series has mostly focused upon Automated “Unit” Testing via Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) and Test-Driven Development (TDD) practices, but Unit Testing may not be sufficient.

Why Unit Tests Aren’t Enough

Nut and Bolt Thinking: Strong, but Incomplete

Unit testing is like confirming what stresses a nut and bolt can withstand separately. While this is important, we also need to confirm that the nut and bolt are the same size with the same thread count. If the nut and bolt don’t screw together securely, it doesn’t matter how much stress each can withstand individually.

What Unit Tests Miss: Assumptions Left Unchallenged

Software is the same. Unit tests are myopic. They don’t see the bigger picture. I don’t think that unit testing alone would have identified the units of measure discrepancy in the Mars Orbiter software, since both software teams would have based their unit tests upon the assumption that they were each using the appropriate units of measure. The unit tests for both teams could have passed with flying colors. The discrepancy would have been easily observed when both sets of software were part of the same Software Under Test (SUT) in a test.

Zooming Out: Scope vs. Detail in Testing

Acquiring the bigger picture often requires a tradeoff. Scope and detail are often inversely proportional. If we don’t reduce detail when expanding scope, then the resulting picture becomes so complex that we can’t comprehend it. We can’t see the forest for the trees.

Consider online maps. Street view provides many details, but we can only see at most a block or two in any direction. Zoom out, and we can see neighborhoods, which provide a wider view, but at the loss of details. For example, rather than seeing images of the actual buildings, they become geometric shapes on the neighborhood map. Continue zooming out and we get a wider view of the city, region, country and world, but details disappear. We quickly lose buildings, local landmarks, smaller roads and even whole communities. Each time we zoom out, we see more scope, but we also lose more details.

Urban Planning: Three Roles, Three Perspectives

Let’s continue the scope/detail tradeoff with urban planning and see how it applies to three different types of civil servants in their roles and responsibilities.

Building Code Inspector

Building code inspectors make sure that buildings are safe for occupancy. They check that the construction, plumbing, electrical systems, etc. are up to code.

Their scope is limited to the building they are expecting, and their only concerns are the infrastructure within the building they are inspecting. Their role is to ensure the safety of the building by its being up to code, and their responsibility is only that building they are inspecting.

Utility Manager

Utility managers ensure that the utility services for a community are working properly. This could include infrastructure systems for the community, such as water, power, sewage, etc.

Their scope is the management of infrastructure among the buildings in the community and the buildings’ connections to utility infrastructure. Utility manager scope is not necessarily the buildings themselves. Utility managers’ concerns are the details of the utility infrastructure.

City Planner

City planners monitor the entire community.

Their scope is the entire community. They aren’t necessarily concerned about the utility details and building codes so long as they provide a strong foundation for the safety and welfare of the residents of the community. Their concerns are fuzzier. Are areas zoned properly? Are the residents happy? Is business thriving?

The 30,000 Foot View

While the scope vs detail tradeoff can be viewed horizontally as scope expands, we tend to use language that frames it vertically, such as the 1,000-foot view, 10,000-foot view or the 30,000-foot view. We can view more of the landscape at higher elevations, but we see fewer details. These terms probably developed with the aviation industry, but you don’t need a plane to envision it. Zooming in and out of an online map provides the same effect.

The three civil servants are not literally at different elevation levels, but we can think of:

- City planners at the highest level viewing the entire community

- Utility managers at a middle level focused upon infrastructure of the community

- Building code inspectors at the lowest level confirming building safety at the smallest details for the community

From Unit to System: Defining the Test Layers

Just as the civil servants assess different aspects of the community based upon scope, software testing can assess different aspects of a system based upon the SUT that is declared for each test.

Software Under Test

Different types of tests are often characterized in layers as higher-level, mid-level and lower-level testing, but like our civil servants, there’s no literal change in elevation.

Before I dive into test layers, I will describe different tests horizontally via the SUT in each test type.

Consider this design:

Unit Tests: Narrow Focus, Deep Confidence

We can design tests narrowly scoped to only one class, such as: Transaction, Session, Tutor, etc. Any dependencies upon other classes would be replaced by emulating Test Doubles.

These tests specify and confirm the behavior of the class, which includes not just the expected scenarios, but the edge cases too. These tests stress our code. We don’t write tests to show that the code works. We write these tests as experiments to try to break our code. The more test stress our code withstands, the greater confidence we gain in our code. This quote, featured in Test are Experiments, describes it well:

Tests don’t break your code; they break your illusions about the quality of that code. — Maaret Pyhäjärvi.

These tests are generally considered Unit Tests. Using a previous analogy, each class being tested is like a nut or bolt in the system.

Integration & Acceptance Tests: Confirming Cooperation

We design tests scoped to the package, such as leisure program, leisure facility and member. The SUT will include more classes in the design. Any dependencies upon classes in other packages would be replaced by emulating Test Doubles.

These tests specify and confirm the behavior of the package. These tests might describe scenarios similar to the Unit Tests above; however, they focus upon confirming that the classes work together cohesively. These tests don’t cover every nook and cranny in the implementation, since the Unit Tests cover these cases. These tests favor expected scenarios and bypass edge cases. Some edge cases may be too difficult to set up with these tests.

These tests are generally considered Integration Tests, since they confirm the integration of components. They would represent screwing the bolt into the nut to ensure they fit.

There’s a subtype of Integration Test: Acceptance Tests. Acceptance Tests focus upon user specific desired behavior. They derive from Acceptance Criteria, which are artifacts in User Stories. An Acceptance Test isn’t a scenario conceived by a tester or developer. It’s defined by the domain expert.

System Tests: Seeing the Whole Product

We design tests scoped to the entire system. Any dependencies would be external to the system. They might be replaced by emulating Test Doubles, or they might be the actual dependency. These tests specify the behavior of the whole system.

These tests are generally considered System Tests, since they confirm the entire system. The concept of nut and bolt may no longer apply at this level. These tests are concerned with the entire system regardless of the implementation. If desired, we could replace the nuts and bolts of the system with welded joints, and the System Tests should still pass. These tests are often executed manually, since they may involve the UI. Some test frameworks support UIs, but the tests can still be brittle and break with UI changes.

These tests are sometimes called End-to-End Tests (E2E).

NOTE: Replacing a system’s nuts and bolts with welded joints actually happened as described in this 99% Invisible Episode: Structural Integrity/Transcript.

An architectural engineering undergraduate student’s class assignment analyzed the stresses on the recently constructed Citicorp building in New York City. The analysis revealed a 1-in-16 chance of the building collapsing when subjected to hurricane force winds directed upon its corners. For three months in the late 1970s, workers clandestinely replaced the nuts and bolts with welded joints during the overnight hours so that the unaware office workers would not know of the potential danger of their building during their daytime working hours.

Layer Metaphors: Why Top and Bottom Matter

Though System, Integration/Acceptance and Unit Tests are scoped by the horizontal Software Under Test enclosed within them, they are almost always described vertically with System Tests being on the top, Integration/Acceptance Tests in the middle and Unit Tests at the bottom.

There is not always a clear boundary between these layers. It can be a bit fuzzy. A limited behavior-specifying test might involve several classes. Some people might consider it a Unit Test, since it specifies limited behavior. Others might consider it an Integration Test, since it involves several classes. It really doesn’t matter. All automated tests should specify and confirm behavior using the same Give/When/Then structure.

The major distinction between test layers is how much of the actual system is under test. While this doesn’t sound like much of a distinction, it creates subtle differences among the testing layers:

- Lower-level tests tend to:

- Take less time to create than higher-level tests

- Be easier to automate than higher-level tests

- Be easier to set up than higher-level tests

- Be less fragile than higher tests, since higher-level tests may depend upon UIs, which often change

- Be replaced more than higher-level tests during refactoring and redesign

- Cover more code in the aggregate than higher-level tests, specifically the edge cases. An individual lower-level test will cover less code than an individual higher-level test, but the set of lower-level tests will tend to cover more code than the set of higher-level tests

- Be more aligned with the design than higher-level tests, which tend to be more aligned with the system architecture

- Provide greater confidence in the individual software components

- Higher-level tests tend to:

- Provide greater confidence in the overall system

- Find errors between software components more than lower-level tests

- The software responsible for newly introduced errors tends to be easier to isolate when found in failing lower-level tests than higher-level tests, since there is less SUT in lower-level tests and therefore fewer places where the error may reside

Each layer of testing operates at a different scope and brings a different type of confidence. Unit tests give us confidence in logic. Integration or acceptance tests verify boundaries and data flow. System tests simulate real user behavior.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison to help clarify how the layers differ across scope, speed, and fragility:

Comparison of Testing Layer Tactics

| Layer | Scope | Focus | Speed | Fragility | Examples | Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System | Full application + dependencies | End-to-end behavior and user outcomes | Slow | High | Full UI test: login, submit form, get result | Selenium, Cypress, Playwright |

| Integration / Acceptance | Multiple components interacting | Data flow, boundaries, and contracts | Medium | Medium | HTTP API call through service layer | Postman, REST Assured, Pact |

| Unit | Single function or class | Logic correctness in isolation | Fast | Low | Testing a math function or basic behavior | JUnit, pytest, NUnit, Jest |

Each test layer is tactical. Let’s examine several test strategies that favor layers differently.

Test Strategy Showdown: Ice Cream Cone vs Pyramid vs Trophy

Test tactics define test layers, each of which tests the software with different emphasis. Should we use a strategy that focuses upon one tactic more than another

The Ice Cream Cone: Heavy on Manual System Testing

Ice Cream Cone was the test strategy for most of my career. There’s an emphasis upon System Testing, as represented by the broad top of the ice cream cone. There are fewer Integration Tests in the narrow middle and even fewer Unit Tests at the almost non-existent bottom.

We had dedicated QA testers whose mission was to test our system to ensure it was ready for release. QA testers were the final quality gate before deploying the system and releasing it to the customer. There was often an adversarial relationship between developers and testers. Developers would often become annoyed when testers found a bug in their code. Would developers prefer for users to have found their bugs instead?

Pros

Manual System Testing was all we had before we had test frameworks that supported automated testing. We didn’t have the insights to understand the concept of automated testing either. Since so much software production was modeled upon manufacturing processes, QA was the final step before sending it to the customer. It’s all we knew at the time. It wasn’t perfect, or even great, but it was mostly good enough for its day.

While System Testing exclusively may no longer be in vogue, there can be some benefits; mainly, interacting with the system like the user would. The goal isn’t to test the system to find bugs, even if we might find a few that have slipped through the automated testing. The goal of this exploratory manual testing is to allow anyone to tap into their human intuition when interacting with it. Explore the system. Is it easy to navigate? Does it make sense? Is it clunky?

Since this isn’t QA focused, everyone should consider exploratory testing: domain experts, developers and testers. It should expand beyond individual contributors to management and executives too. If you can’t easily use your system, your customer and user won’t be able to easily use it either.

TIP: If you have desktop video recording capability, such as Zoom, share and record your screen and narrate what you’re doing. Describe your intent. Point out what you see. Point out what you expect to see, but don’t. Point out anything that’s odd or confusing. If you have access to logs, databases or any other relevant technical information, show it in the video as well. If you identify a poor user experience or a failure, then a five-minute video will provide more context and takes less time to produce than filling out an extensive How-To-Reproduce documentation in the ticket. Personally, I’ve found video descriptions of issues found by others more useful to me than reading a step-by-step document.

Cons

So much garbage was thrown over the wall by developers to QA, usually to meet an artificial deadline. We hoped that any serious problems in our code would be found by QA. If it slipped through, then well, that was QA’s fault. Testers would also be annoyed when they found obvious bugs that the developers should have found on their own. This was during the days of the Waterfall Methodology, and a lot of garbage was thrown over almost every wall in the process, not just developers to QA.

When programmers do their jobs, testers find nothing. — Bob Martin

Most System Testing was manual. Manual testing is slow, error prone and mind-numbing. Sometimes QA would get last minute updates with barely any time to run tests before release. There was a lot of sitting around waiting for code and then a mass rush to execute as many tests as possible to meet the delivery date.

Computers are designed to do simple repetitive tasks. As soon as you have humans doing repetitive tasks on behalf of computers, they all get together late at night and laugh at you. — Neal Ford

There’s a limit to what System Tests can achieve. While System Tests can confirm many behaviors, it can be difficult to set up edge case scenarios.

The feedback loop for developers is too long. It could take several days before QA received a new version of code, then a few more days until an error was revealed in a manually executed test scenario. It could take a week or more before a bug was identified, investigated and assigned to a developer.

Automated System Testing frameworks are becoming more prevalent, but they can still be brittle when they depend upon the UI.

The Pyramid: Base of Confidence through Automation

The Pyramid Test Strategy flips the Ice Cream Cone Test Strategy. In Pyramid Testing, there are many Unit Tests at the bottom, representing the base of the pyramid, with fewer Integration/Acceptance Tests representing the middle of the pyramid and finally the fewest System Tests at the apex.

Pros

Lower-level tests tend to accommodate automated tests, so this strategy tends to work well with CI/CD pipelines. An entire test suite can be executed on each commit to a major branch easily.

The software elements should have nearly complete coverage. Working elements don’t guarantee a working system, but flawed elements will almost certainly guarantee a flawed system.

Since Unit Tests tend to specify units of behavior, each Unit Test tends to execute a limited number of statements. Therefore, when a Unit Test fails, run the failing tests in isolation with code coverage activated, and the limited number of covered lines should be the first place you look for the error.

Cons

Since there’s more emphasis on the lower-level tests than the mid-level tests, we can run into the situation of having great confidence in the software elements, but not as much confidence in the overall system.

Since tests specify behavior with a class, any refactoring or redesign that affects classes will tend to affect tests. When implementation is moved among classes, then the tests that defined those behaviors will probably need to be decomposed, moved and reassembled with the refactored and redesigned implementation as well.

The Trophy: Centering on User-Centric Acceptance

The Trophy Test Strategy focuses upon Integration/Acceptance Tests. This is represented in the silhouette of Trophy Cup with few System Tests at the top, most tests in the middle with Integration/Acceptance Tests and a few Unit Tests underneath. The Trophy Test Strategy also includes a pedestal, which represents Static Analysis Tests, which are linters that check the implementation for coding standards and practices. The other test strategies tend to include them as well, but they don’t tend to show up in their definitions.

Pros

The theory behind the Trophy Test Strategy is that we want to focus upon customer and user desired behaviors, which would be defined in Acceptance Tests. The customer doesn’t care about the implementation, so we shouldn’t dedicate many resources to tests that are aligned with the design. The customer only cares about the features they will be using, and Acceptance Tests describe the scenarios for those features independent of the implementation.

The Integration/Acceptance Tests would tend to cover a significant amount of code. Unit Tests would be added to cover the remaining code. These tests tend to be edge case code that can’t easily be covered via Integration/Acceptance Tests.

Since Acceptance Tests describe feature behavior, not design behavior, refactoring and redesign should have minimal impact upon Acceptance Tests. And since there are fewer Unit Tests, there should be fewer Unit Tests that need to be updated.

Cons

An Integration/Acceptance Test will tend to execute more lines of code than a Unit Test. When an Integration/Acceptance Test fails, it will take more effort to find and fix the problem. Debugging will mostly likely be required. When a Unit Test fails, it tends to execute less code, possibly fewer than ten lines. While some degree of debugging may be required, the search area for that bug is smaller.

Since Integration/Acceptance Tests aren’t scoped to a specific class, there may not be a quick suite of tests to confirm a class while you’re working on it.

Which Strategy is best?

Which strategy is best? That depends on your context.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the Ice Cream Cone, Pyramid, and Trophy test strategies to help highlight their trade-offs:

Comparison of Testing Layer Strategies

| Strategy | Emphasis | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best Used When… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ice Cream Cone | Heavy system tests, few unit tests | High user-centered coverage | Slow, fragile, poor fault isolation | Starting out, exploratory environments |

| Pyramid | Many unit tests, fewer system tests | Fast, stable, good coverage at low cost | Can miss integration/system-level issues | Mature projects with modular code |

| Trophy | Strong integration, moderate unit/system | Balances confidence and real-world testing | Needs robust integration infrastructure | Microservices, API-heavy architectures |

Yes, And: Combining Strategies Effectively

Test Strategies are not mutually exclusive. It’s not a case of either/or. It’s yes, and.

I tend to prefer the Pyramid Test Strategy, but I’m not averse to the Trophy Test Strategy. You can leverage both. Use Test Strategies where they best fit. Some classes may tend to lean toward Pyramid. Some may tend to lean toward Trophy. And then with the confidence you gain in the code from Pyramid/Trophy Testing, you can always add exploratory manual System Testing on top not to look for errors, but to make sure that the system still feels like a cohesive product.

It can be the best of all worlds.

The Achilles Heel: When Test Layers Aren’t Enough

There is one vulnerability.

The Problem of Composable Designs

Higher-level testing cannot easily test one type of design paradigm: Composable Design Patterns.

Behavior emerges from a composable design via the interaction of objects, which are assembled at run-time. Unit Tests can specify and confirm behavior for individual classes in isolation. Unit/Integration Tests can also confirm that the objects are created and assembled in various combinations. Unit/Integration Tests can confirm the behaviors that emerge from test specified object compositions.

However, developers and testers won’t be able to cover all possible scenarios. This is not a case of developer or tester incompetence. Object composition may be unlimited. It’s impossible to cover all possible scenarios when there’s a potentially infinite number of them.

For some designs, the configuration of compositions might remain within control of development. This limited set of compositions can be tested via Integration Tests. But when behavior composition is available to users, customers or even customer support, they are free to define any compositions. These cannot be tested, since they may not be defined until long after the software has been released.

The more composition options a design supports, the quicker the composition combinatorics explode. The Interpreter Design Pattern supports the most composition options. We can test each of the elements of an Interpreter design easily. We can’t test all the composition possibilities.

Lessons from Compilers: You Can’t Test Every Combination

This is not a new problem. Compiler developers have always had this issue. Compiler developers can confirm that their compilers generate object code from the source code correctly, but they can’t predict every program that could be written in the compiler’s language and test it. No one blames JVM developers when there’s a logic bug in their own Java code.

While we can’t confirm all possible compositions, we can confirm all the individual elements, just as the compiler developer can confirm all possible language features. While composable designs may be unbounded in the size of their assembly, their assembly is often restricted by guardrails defining how the elements can be assembled. While users and customers may be able to define compositions that don’t define exactly what they wanted, they cannot define compositions that are illegal in the domain. For example, a Java developer can write a Java program with a logic error, but they cannot write a compliable Java program with a syntax error.

What Test Layers Teach Us About Software Quality

Testing isn’t just about proving that our code works—it’s about building confidence in its behavior under a range of conditions, at multiple levels of abstraction. Unit tests confirm that our building blocks are sound. Integration and acceptance tests ensure those blocks fit together. System tests assess the final structure and its behavior in the real world. Each test layer serves a different purpose, and together, they create a safety net that helps us catch errors before our users do.

Too often, teams rely on a single strategy—leaning too heavily on high-level manual testing or obsessing over granular unit tests without confirming how components collaborate. By understanding test layers through analogies like nuts and bolts, urban infrastructure, or zooming maps, we gain an intuitive model for balancing scope and detail.

No one strategy fits every project. Whether you favor the Pyramid, Trophy, or Ice Cream Cone model, thoughtful layering of tests gives your team the agility to move fast without sacrificing safety. And as we’ve seen with composable designs, even the most thorough test suites can’t cover every possible combination—especially when behavior is assembled dynamically. That’s why building robust, flexible components and placing strategic guardrails is just as important as writing tests.

The goal is not perfection—it’s confidence. Confidence to refactor boldly. Confidence to release frequently. Confidence that when something goes wrong, you’ll catch it early. When we test with both discipline and empathy, we’re not just verifying code—we’re building trust.