Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

Delegate a request through a linked chain of handlers until one of the handlers can complete the request.

Introduction

The Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern is the next of the Composable Design Patterns series.

Chain of Responsibility (CoR) delegates a request through a set of handlers until one can complete the request. The handlers are organized in a linked list, i.e., the chain, such that the least resource intensive handlers tend to reside earlier in the list and the more resource intensive handlers reside later in the list.

Chain of Responsibility can trace its roots back to the Strategy design pattern, as can almost every pattern I’ve presented since Strategy. With CoR, each handler is a strategy option, but the CoR design is not limited to choosing one strategy. Strategies, as handlers, can be chained together dynamically so that if one strategy is not applicable, then there may be another one down the chain that will be.

Real World Analogies to Chain of Responsibility

Like Decorator, CoR is not difficult to implement. Its main challenge is comprehension. Here are a few real-world examples to ease one into the CoR concept.

Customer Support

Almost everyone has called customer support with an issue at some point. Customer support begins with a bank of front-line representatives doing their best to resolve the issue. But sometimes, they cannot, because they may not have the authority to resolve a challenging issue.

The customer may escalate by asking to speak to a manager, who has additional authority to resolve the issue. If the manager cannot resolve the issue, then the customer may escalate to the manager’s manager.

The customer may continue to escalate until either their issue is resolved, or they run out of managers.

Customer support is a Chain of Responsibility starting front-line representatives and proceeding through managers. The front-line representatives have enough authority for most issues, but they may not have enough authority for more the challenging ones. Front-line representatives can handle most requests, leaving the more challenging requests to the diminishing number of managers through the management chain who have more authority for the more challenging issues.

The Judicial System

The Judicial System in the United States is a type of Chain of Responsibility.

If a party in a legal dispute is dissatisfied, they have the option to appeal the decision to a higher court. This proceeds until the dissatisfied party is satisfied, the court refuses to hear the case, or the case reaches the highest court in the land.

$PATH in Unix/Linux

In Unix/Linux, you can type the name of an executable from the command line. The desired executable can be in almost any directory in the system.

$PATH is a shell variable that’s comprised of a colon separated list of directories where executables reside.

Unix/Linux will look for the executable one directory at a time in the $PATH list.

It will execute the first one it finds that matches the name.

This behavior is Chain of Responsibility.

Other PATH variables are also used to find libraries, classes, man pages, etc. They exist in other operating systems too.

Caches

A Cache is a Chain of Responsibility.

Caches are quick, yet not always complete repositories of information. If information is not found in a cache, then it is retrieved from a more resource intensive source of truth such as a database or web service.

Bloom Filter

A Bloom Filter is a Chain of Responsibility, mainly because it’s a form of cache.

It’s a space-efficient probabilistic algorithm that will efficiently determine with 100% accuracy if a piece of information is not in a data store, but it is not reliable when the information is present in the data store. I.e., its responses should be interpreted as:

- A 100% guarantee when the information is not in the data store.

- No guarantee when the information is in the data store. A 100% guarantee is only possible by moving past the Bloom filter and accessing the data store directly.

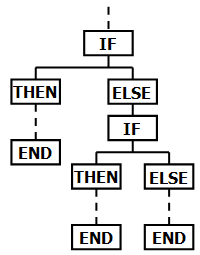

Switch and Cascading If/Else-If/Else Statements

switch statements and cascading if/else-if/else statements are a form of Chain of Responsibility. The flow of control proceeds through the conditions until the first one is satisfied, and then its corresponding statement body is executed.

The main difference between switch/if/else-if/else and CoR is that the former is statically locked in the code and the latter is dynamic. This is not unlike the comparison of inheritance and the Decorator design pattern.

I’m not a huge fan of switch/if/else-if/else in the code base. I’ve encountered them being replicated repeatedly for different behaviors throughout the code base, rather organizing and encapsulating behaviors within their respective classes. switch/if/else-if/else code is difficult to understand and maintain. This is a code smell and really a topic for another blog (TBD).

Sometimes these control flow structures are needed for algorithmic or business policy. For me, they become code smells when the control flow structures are based upon different type variations of the same common theme.

Design Structure

Chain of Responsibility and Decorator are almost identical structurally, but they are distinct in behavior. I will highlight their similarities and differences before getting into the CoR’s design structure.

How Chain of Responsibility and Decorator are the same

The UML class diagrams for Chain of Responsibility and Decorator look almost identical. Both feature an abstract class that delegates back to a version of itself. This defines the linked list for both.

Both patterns feature delegating calls down the linked list.

Properties of the linked list are so similar that the same delegate reference can be used for both CoR and Decorator behavior in the same class, and in some cases, even in the same method.

How Chain of Responsibility and Decorator are different

The primary difference between Chain of Responsibility and Decorator is in how they delegate down the linked list.

Decorator always delegates down the linked list to the anchor object at the end and returns. Each object in the list can apply different behaviors on the delegate calls down the linked list and/or on the returns coming back. All objects in the list are always executed and all contribute to the aggregate behavior.

Chain of Responsibility delegates down the linked list until one of the handler objects in the linked list can complete the request. That handler completes the request, and flow returns back the list without traversing to the other handlers in the list. If the first handler object in the list is sufficient, then no other handler objects are executed. Only one handler object in the list handles the request and none of the others contribute to the completion of the request.

It’s also possible that no object in the linked list can complete the request.

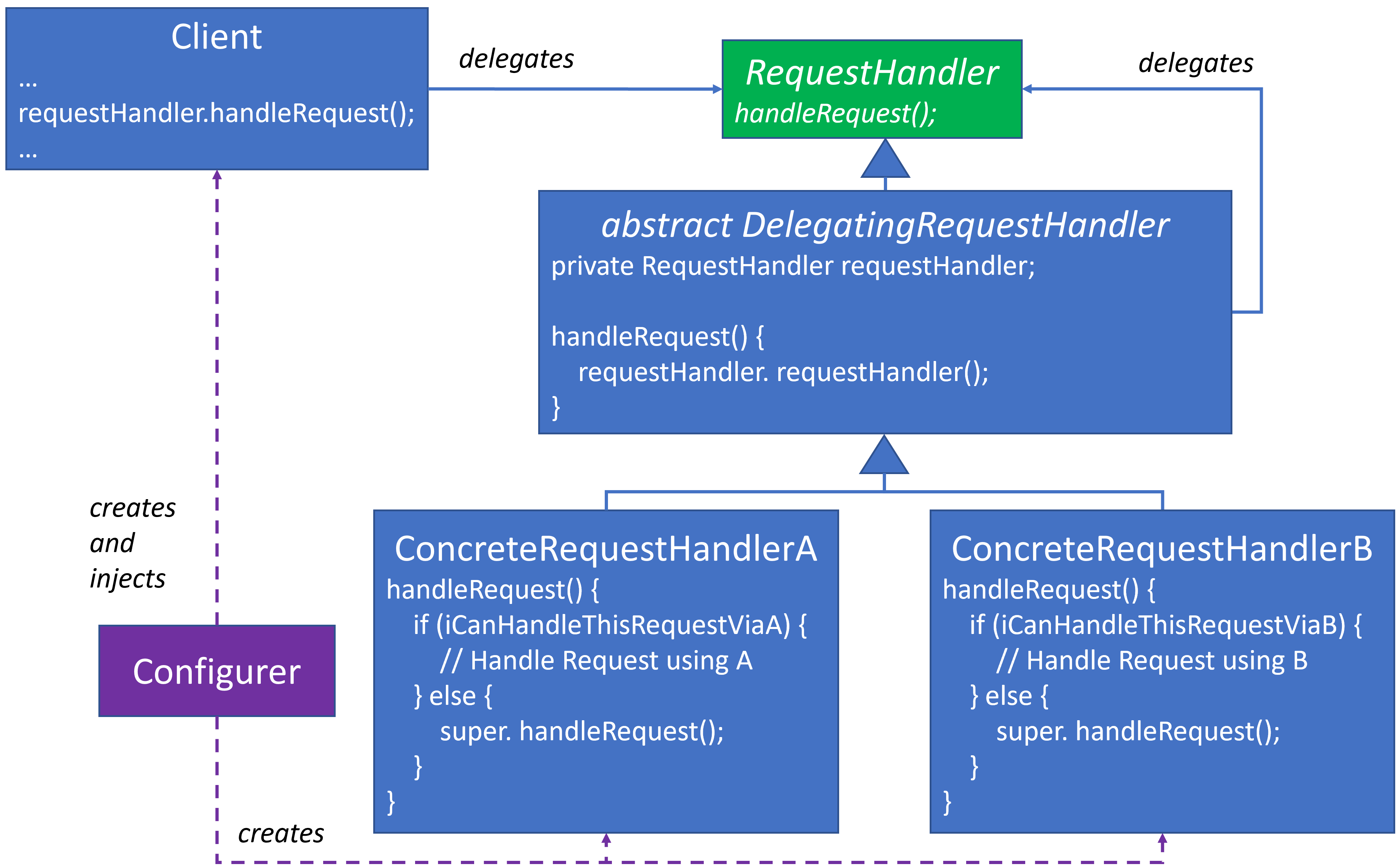

GoF Chain of Responsibility

Here’s a summary of the GoF’s CoR design:

- I added a

RequestHandlerinterface, which the GoF does not include in their diagram. I prefer an interface contract at the top of the design. In the GoF, their abstractDelegatingRequestHandler’s delegating reference is back itself. DelegatingRequestHandlerimplementsRequestHandler’shandleRequest()by delegating to its handler reference.- The real work resides in the concrete classes that extend

DelegatingRequestHandler. I’ve provided two as an example. One uses A and the other uses B. These are placeholder names for specific request handler mechanisms, which could be caches, databases, etc. - Each concrete class determines whether it can handle the request and if so, it handles it. Otherwise, it delegates to the base class

handleRequest(), which delegates to the next handler in the linked list. - The

Configurer, which is not represented in the GoF’s diagram, creates the concrete handler instances, arranges them as a linked list and injects them into theClient. - The

Clienthas no dependency upon or knowledge of the concrete handlers. It only has a reference to aRequestHandlerfrom which it callshandleRequest().

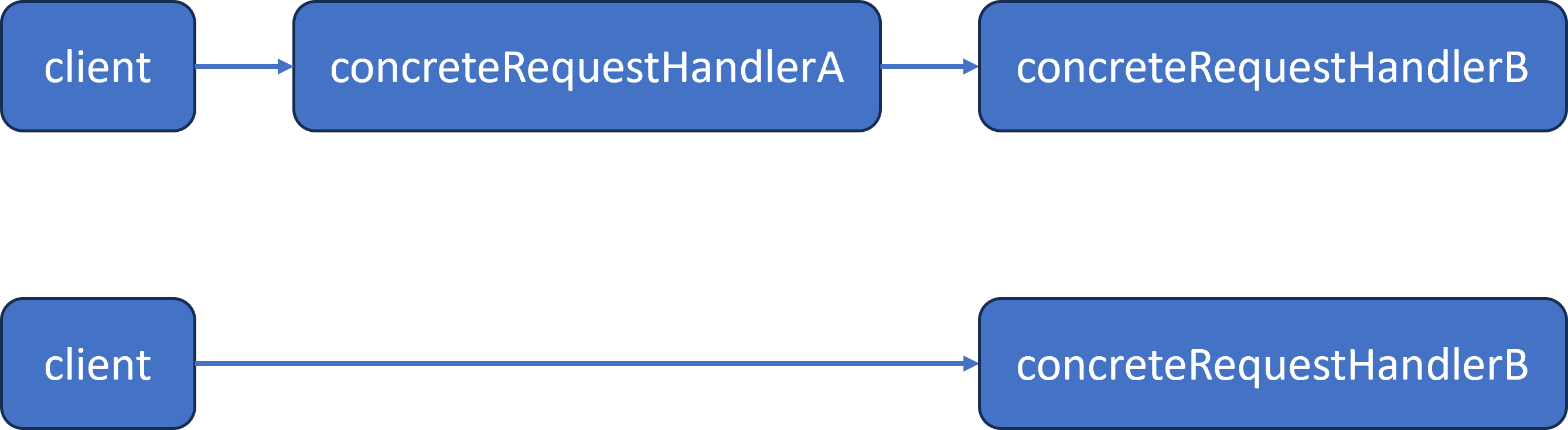

Here’s an example of the linked list of objects that can be created for this design:

In this example, B is the more reliable and more resource intense handler. A is the less reliable and less resource intense handler. While we could configure an A handler after the B handler, there’s no logical reason to do so.

Much like the GoF’s Decorator design, I have a few issues with their Chain of Responsibility design:

- If the GoF observed their own design principles, then I would have expected an interface at the top of their design.

- Their design demands too much responsibility of the concrete classes. Their design requires a lot of faith that the concrete class developer will get the

if/elselogic right. - I don’t like that the

elsecase requires a call to the base class viasuper.handleRequest(). This violates encapsulation. - There’s no guarantee that any of the handlers will be able to handle the request. If that’s the case, then the call to

super.handleRequest()will encounter a null reference. The GoF put a null check in their example C++ code, but the concept is not represented in the design.

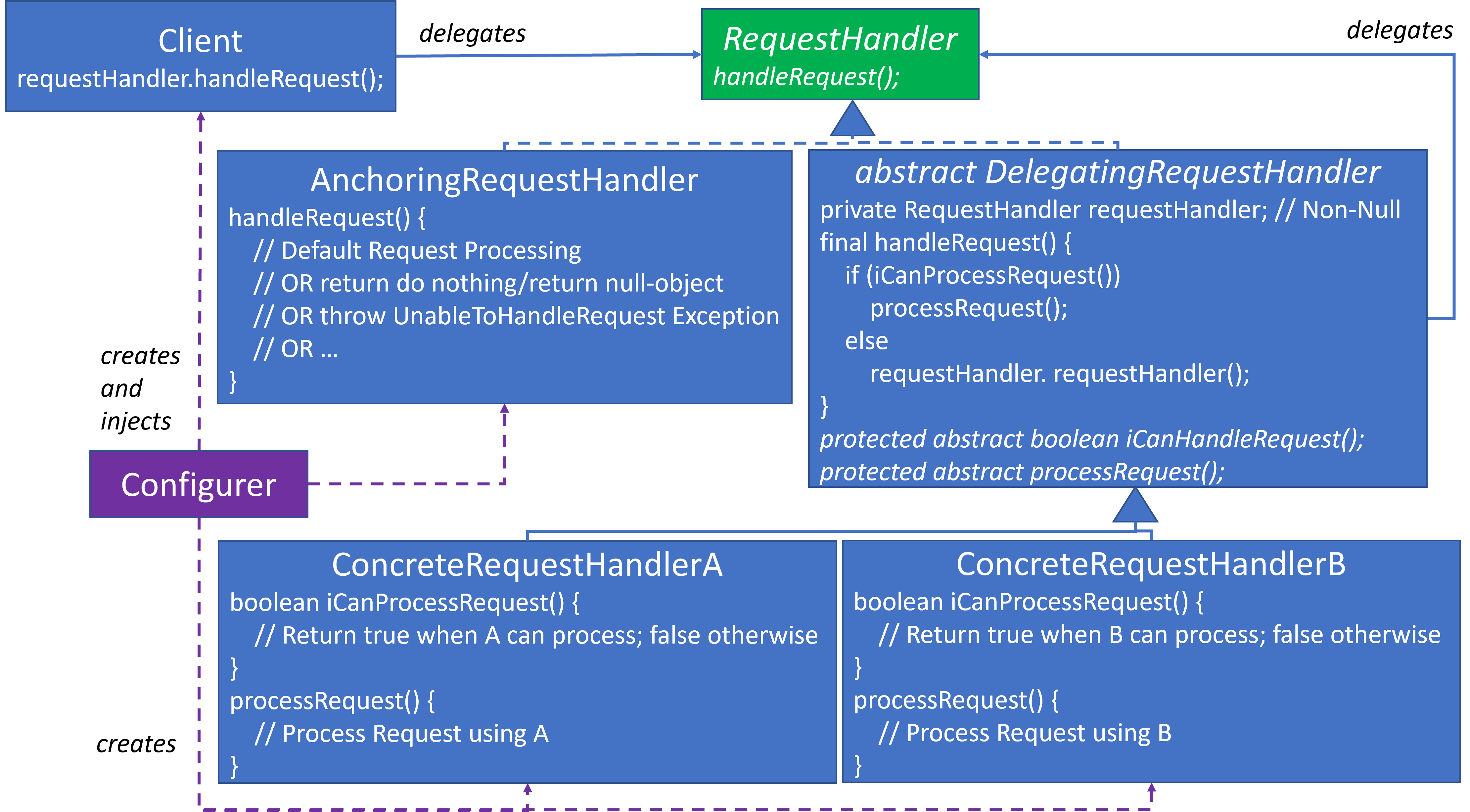

Chain of Responsibility with Template Method

I want to remove my depending upon faith in my fellow developers to get everything right in the concrete handlers.

This design incorporates the Template Method Design Pattern into the design, much as I did with Decorator:

- The logic to delegate down the chain has been moved up to the abstract

DelegatingRequestHandlerinhandleRequest(). Delegating down the chain is no longer the responsibility of the concrete handler classes or their developers. - Though

DelegatingRequestHandler.handleRequest()contains the delegating logic, it still depends upon two abstract methods,iCanProcessRequest()andprocessRequest(), for concrete behavior specifics. Each concrete handler must implement both of these methods. ConcreteRequestHandlerAandConcreteRequestHandlerBeach implementiCanProcessRequest()andprocessRequest()as mentioned above, but relative to A and B respectively. The concrete handlers don’t know they are part of a chain. Their only concerns are whether they can handle the request and handle its processing.DelegatingRequestHandler.handleRequest()only requires two test cases:- Confirm that

processRequest()is executed, wheniCanProcessRequest()returns true. - Confirm that

requestHandler.requestHandler()is executed, wheniCanProcessRequest()returns false.

- Confirm that

DelegatingRequestHandler.handleRequest()is declared asfinalso that a concrete handler cannot override it, even if unintentionally.DelegatingRequestHandler’srequestHandlerfield attribute is described as Non-Null. This ensures that when it’s referenced, it won’t throw anNullPointerException. I do not show how this Non-Nullness can be achieved since there was insufficient space to present it. If I had the space, theDelegatingRequestHandlerwould define a constructor with aRequestHandlerparameter. The constructor would throw an exception if it were null.DelegatingRequestHandler’s non-nullrequestHandlerconstraint means that each linked list chain must end with a non-delegating handler, which in this design isAnchoringRequestHandler. There’s no guarantee that any request handler will be able to handle the request. When the flow reachesAnchoringRequestHandlerthen the request has gone unhandled.AnchoringRequestHandlerserves the same function as thedefaultin aswitchstatement or theelseof a cascading set ofif/else-ifstatements. Default behavior will vary based upon context. I’ve provided a few options as comments within the design.

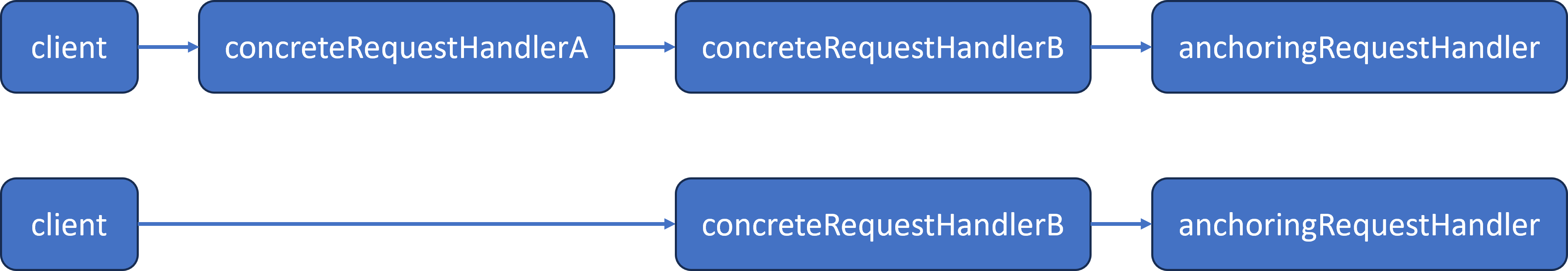

Here’s an example of the linked list of objects that can be created for this design, which is the same as the objects in the GoF’s CoR example, but with the addition of anchoringRequestHandler at the end of the chain:

Use Case – Address Book

This Chain of Responsibility Use Case example is based upon an actual work assignment I had.

The Problem Scenario

One day our PM/CTO called me into his office. He described a data management situation to me. Rather than attempt to recreate a 12-year-old conversation from memory, I’ll highlight the main points:

- Our customer’s organization was highly hierarchical and dynamic.

- Users needed to know their place in the organization hierarchy which could change at any time due to its dynamic nature.

- Organization hierarchy had two data stores: a database and a webservice.

- Due to resource constraints of the users, some only had access to the database. Some only had access to the webservice. Some had access to both.

- The webservice was the source of truth. The database was a copy for those users who didn’t have access to the webservice.

- He wanted a cache if possible.

- There was also the possibility that another organization’s hierarchy could be added in the future, and could the design accommodate that too? This never happened while I was on the project, but it was something to keep in mind.

He asked if I knew of any design pattern that might help with this.

Chaining Data Sources

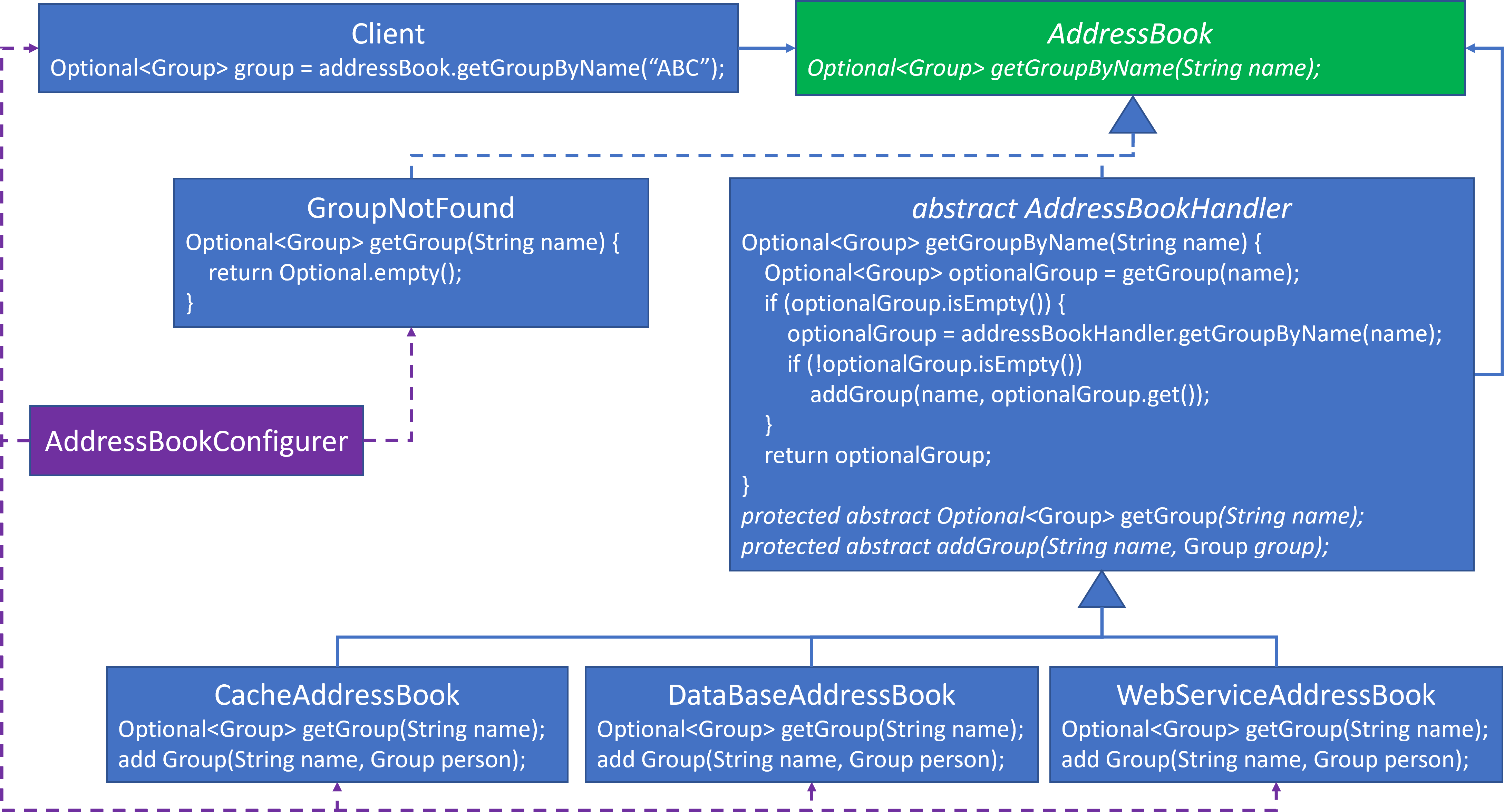

While I had never used Chain of Responsibility, it was the first idea that came to my mind. I went through several design iterations before settling upon something like this design:

- I called it an

AddressBook. I envisioned a swinging bachelor from the 1960s who might look for a phone number for a weekend date by first consulting his little black book and then the regular phone book and finally call directory assistance as his options dwindled. - I’m calling the organizational entity a Group in this example. It’s a generic term. It can represent any named Group at any position in the organizational hierarchy.

- The

AddressBookreturns anOptional<Group>upon a look up rather thanGroup, since it’s possible that there may not be aGroupby that name in the organization. I don’t want the caller to have to deal with a nullGroupobject being returned. AddressBookHandleris where most of the design details resides. It’s using Template Method, but it’s slightly different than what was shown with the generic CoR Template Method example above:- There is no separate

iCanProcessRequest()andprocessRequest()methods. Both behaviors are represented inOptional<Group> getGroup(String name). - When

Optional<Group>is not empty, then the request has been completed, and theOptional<Group>can be returned. - When

Optional<Group>is empty, then delegate the request to the nextAddressBookand return whatever it returns, even if empty. - When delegating to the next

AddressBookand it returns a non-emptyOptional<roup>, then this design takes the opportunity to add the missingGroupinto the currentAddressBookHandler. This is not part of the GoF’s CoR design, but I have included it mostly to populate the cache. This additional behavior to calladdGroup(String name, Group group)is the Decorator design pattern.

- There is no separate

AddressBookHandlerhas three paths of execution that need to be tested:- When

getGroup(name)finds aGroupand returns a non-emptyOptional<Group>. - When

getGroup(name)does not find aGroupand returns an emptyOptional<Group>, and then:addressBookHandler.getGroupByName(name)finds aGroupand returns a non-emptyOptional<Group>.addressBookHandler.getGroupByName(name)does not find aGroupand returns an emptyOptional<Group>.

- When

GroupNotFoundreturns an emptyOptional<Group>in all cases as the default behavior since none of theAddressBookHandlerswere able to find aGroupby name.

Concrete AddressBookHandlers

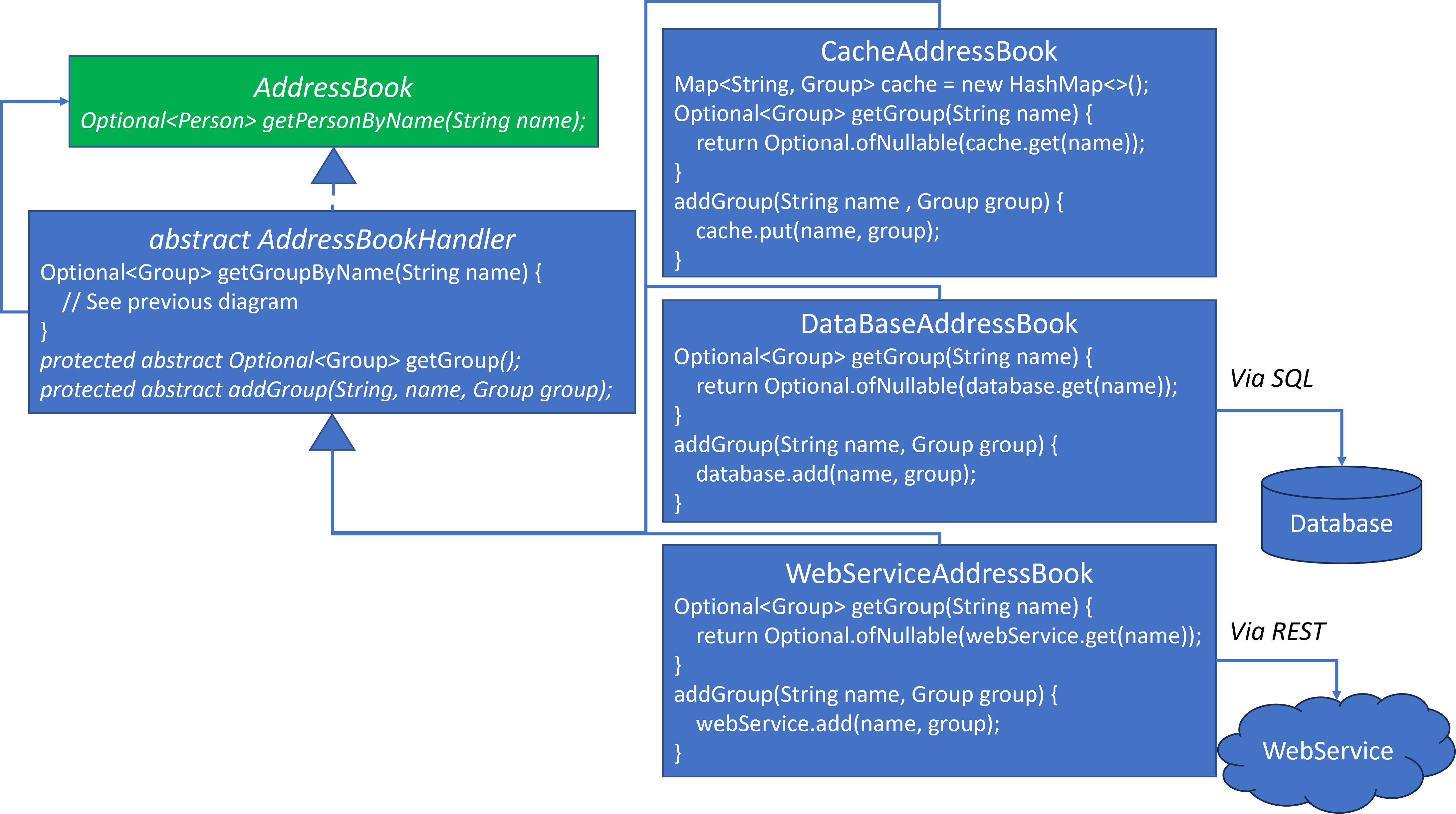

I can’t quite fit the entire design on one diagram, since the AddressBookHandler details required considerable space.

If this were a design only for me, I would not have added the concrete classes above.

The abstract AddressBookHandler would have been sufficient for the design on that page.

But since this design is trying to convey the overall design, I included them above.

Here is the second part of the design, which provides some additional design details for the concrete AddressBooks:

- This diagram replicates the AddressBook classes from the previous diagram, but it focuses more upon the concrete AddressBooks.

- Each concrete AddressBook implements the protected methods declared in

AddressBookHandler. CacheAddressBookimplements the methods via aMap.DataBaseAddressBookis grossly simplified. There’s insufficient room to represent more. What’s important is thatDataBaseAddressBookdelegates to the externalDatabase, possibly via SQL. This delegation is an example of the Adapter design pattern.WebServiceAddressBookis likewise the same asDataBaseAddressBook. It’s also grossly simplified due to space constraints. It delegates to theWebServicepossibly via REST. This delegation is also an example of the Adapter design pattern.

If this were a design just for me, it would have started with the abstract AddressBookHandler as before, but without the AddressBook interface it implements. And if more space were needed for each concrete Address Book class, then the above could have been split into three separate diagrams to provide additional details for each concrete class as needed.

Cache Invalidation

The design as shown has an issue with stale cached Groups. I mentioned that the organizational hierarchy was dynamic. It could change at any time. As designed, once a Group is in the cache, it’s never updated or removed.

We were able to accommodate for this with another design feature in the real project, which I’ll describe briefly, but I won’t represent in the design example.

We subscribed to updates and deletions from the Database and the WebService. When we received a notification that a Group had been updated or deleted, we deleted it from the Cache. A fresh version would be repopulated in the Cache upon the next request that referenced it.

The subscription and notification mechanism is the Observer design pattern, which I’ve not mentioned previously, but I plan to blog (TBD) about it in the future.

And to be technically accurate, our DataBaseAddressBook did not add the Group to the Database in its addGroup(String name, Group group) method. Another organization was responsible for the Database’s content. We only had read-only permission. Therefore the addGroup(String name, Group group) method, for which an implementation was required, was an empty method. The same was true for WebServiceAddressBook.addGroup(String name, Group group) method for similar reasons.

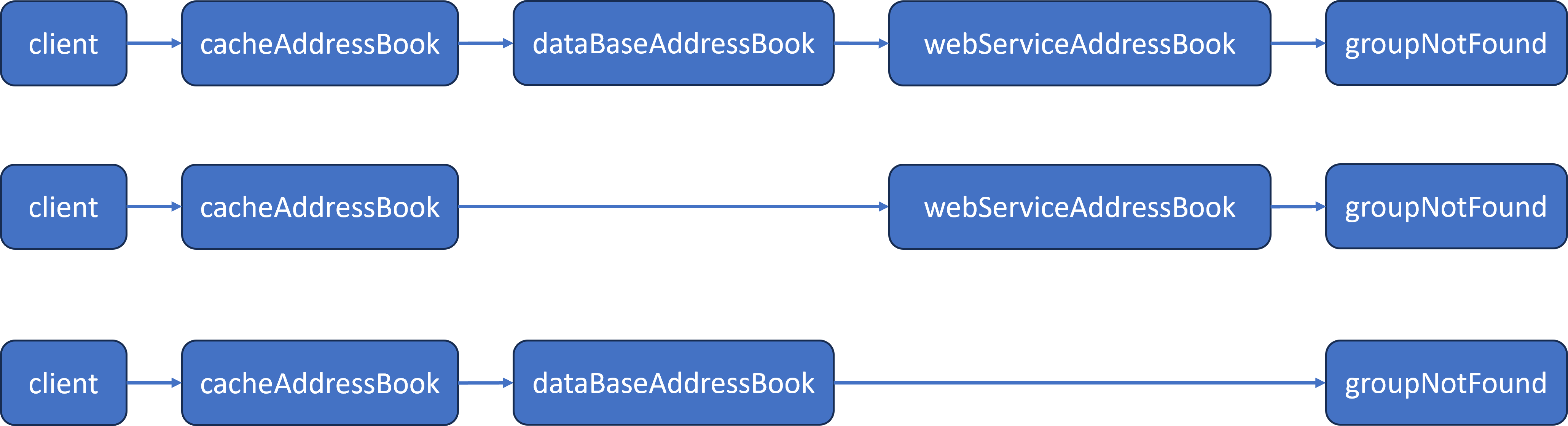

Configurer

Composable designs provide structural potential but not behavior. The behavior must be composed by a Configurer type of class.

My PM/CTO had described the possible configurations. They would be:

My first Configurer implementation was based upon building the linked list chain from a configuration String value, such as:

ADDRESSBOOK_PATH=Cache:DataBase:WebService:GroupNotFoundADDRESSBOOK_PATH=Cache:WebService:GroupNotFoundADDRESSBOOK_PATH=Cache:DataBase:GroupNotFound

The Configurer would split $ADDRESSBOOK_PATH with a colon delimiter, acquire the corresponding object from an AddressBookFactory, not shown in the diagram, and chain them together into a linked list.

This worked fine in my testing, but it was not a good production quality solution. Our product was part of a fleet embedded systems for which there could be hundreds if not thousands of individual systems. Configuring each embedded system correctly was not realistic.

The first obvious observation was that ADDRESSBOOK_PATH always started with Cache and ended with GroupNotFound. The only parts that varied were DataBase and WebService.

Other environment variables implied whether the DataBase or a WebService was accessible in each environment. Therefore, I updated the Configurer so that it constructed ADDRESSBOOK_PATH based upon known values and environment variables. The configuration issue evaporated.

Introducing a new Organization

My PM/CTO had hinted that the AddressBook might need to accommodate a sibling organization in addition to the original customer. As I mentioned above, that never materialized.

However, if it were to materialize, then we would have had to consider the following:

- The sibling organization might have different concepts for a

Group. We might have had to either translate the second organization’s terminology into the existingGroupor potentially normalizeGroupsuch that it would work for both organizations possibly with translation for both organizations. - There could be several linked list chain management strategies including:

- Create a chain comprised of

AddressBookHandlers from both organizations. - Ascertain the organization from its name, and then configure a chain on the fly that consisted of only

AddressBookHandlers for that organization. - Ascertain the organization from other environment variables, and then configure a chain on the fly that consisted of only

AddressBookHandlers for that organization. - Others? Composition resides in the

Configurer, which is unstable/flexible and therefore invisible to the rest of the design. We could try different approaches and update them without an impact upon the rest of the design.

- Create a chain comprised of

Pattern Review

The AddressBook use case features more than just Chain of Responsibility. Design patterns are rarely used in isolation. They often work together.

Here’s a quick summary of the design patterns featured or mentioned in this use case:

- Chain of Responsibility the pattern of this blog.

- Strategy as the foundation pattern which CoR extends.

- Template Method to move most of the CoR behavior into the abstract class and away from the concrete Address Book handlers and their developers.

- Decorator to populate the Cache and other Address Book Handlers when an unfound

Groupis found by a subsequent handler. - Adapter to allow the design to interact with external entities, such as a Database and WebService.

- Observer to keep the Cache up to date, but it’s only mentioned in this blog, not featured.

Chain of Responsibility Pros and Cons

The relative pros and cons of Chain of Responsibility are like those with most of the Composable design patterns.

Cons

Composable behavior may be more difficult to diagnose with Chain of Responsibility. While it should be simple to understand individual concrete classes in a CoR design, the responsibility to orchestrate observable behavior resides in the Configurer.

Integration or acceptance tests may be needed to confirm that desired behavior emerges when the objects are composed.

Pros

Chain of Responsibility’s composable behavior is also a pro. Behavior is not hardcoded into place as is the case with switch or if/else-if/else statements. When a new responsibility chain is desired, it may be a relatively simple matter of a new composition of objects instantiated from the existing handler classes in the design.

Sometimes new handler responsibility is beyond the scope of a new composition. A new handler class may need to be implemented. Existing concrete classes can be implementation references to provide examples for new concrete class implementation.

The classes can be unit tested with ease. Even the abstract DelegatingRequestHandler class can be unit tested with a dependency upon a test double without depending upon another concrete class in the design.

There may be many concrete classes in a CoR design, but they tend to be independent. They don’t depend upon or know about each other. Therefore, new concrete classes can be added with fear of breaking existing classes. It’s also easier to identify and remove deprecated classes when they are no longer needed.

Summary

Chain of Responsibility provides flexibility within a design. CoR is an extension of the Strategy design pattern. Each concrete handler is a strategy option, but within the context of CoR, the design is not limited to one strategy at a time. Strategies, as handlers, can be chained together dynamically so that if one strategy is not applicable, then there may be another one down the chain that will be.

References

There are many online resources with diagrams and implementations in different programming languages. Here are some free resources:

- Wikipedia Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- Source Making Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- Refactoring Guru Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- Project Management Institute Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- Baeldung Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- OODesign Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- Learn CS Design Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- DoFactory Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- hackernoon Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

- and for more, Google: Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

- Gang of Four Chain of Responsibility Design Pattern, page 223 (O’Reilly and Amazon)

- Clean Code: Design Patterns, Episode 34 video (Clean Coders and O’Reilly)