Interpreter Design Pattern – Grammar to Design

The Interpreter Design emerges from the Grammar.

Introduction

This blog continues the Interpreter Design Pattern series by expanding upon how the Interpreter Design emerges from the Grammar, which I introduced in Interpreter Design Pattern – Grammar to Design.

This is the blog in the Interpreter series that highlights the elegance of the Interpreter design pattern. This is where the magic happens.

Design for the Interpreter Design Pattern by the Gang of Four

Let’s return the Gang of Four’s (GoF) words about Interpreter. Hopefully this paragraph makes a bit more sense than when I posted it a few blogs ago:

If a particular kind of problem occurs often enough, then it might be worthwhile to express instances of the problem as sentences in a simple language. Then you can build an interpreter that solves the problem by interpreting these sentences.

I’ve written about the kind of problem and simple language as Domain-Specific Languages (DSL). My previous blog, Interpreter Design Pattern – Grammars, focused upon defining a grammar for a DSL. This blog will focus upon creating a class design that supports the grammar.

The GoF’s Interpreter Class Design is the following:

Their design is more of a template for Interpreter rather than a complete design. Compare this design to the Composite Design Pattern, and you’ll notice that it is structurally identical to Composite, but with the addition of Context. Context allows us to inject additional information. In the Specification Smart Playlist Use Case, the Track was the injected Context. Different tracks with different attribute values would result in different specification matching results. Context will be uniquely designed for each DSL, since each DSL may have unique information concerns.

The GoF’s AbstractExpression, TerminalExpression and NonterminalExpression elements in the diagram suggest only one type of each. In practice, there will be many interfaces and classes of each type. There will be more domain specific relationships among these elements.

The GoF’s diagram is missing much of the richness and elegance of the pattern. They hinted at the richness and elegance in their Regular Expression Interpreter example, but they didn’t follow through.

The GoF provide a grammar for their Regular Expression Interpreter example without providing any details as to how they created the grammar:

expression ::= literal | alternation | sequence | repetition | ‘(’ expression ‘)’

alternation ::= expression ‘|’ expression

sequence ::= expression ‘&’ expression

repetition ::= expression ‘*’

literal ::= ‘a’ | ‘b’ | ‘c’ | … { ‘a’ | ‘b’ | ‘c’ | … }*

They provide some description with the following:

The symbol expression is the start symbol, and literal is a terminal symbol defining simple words.

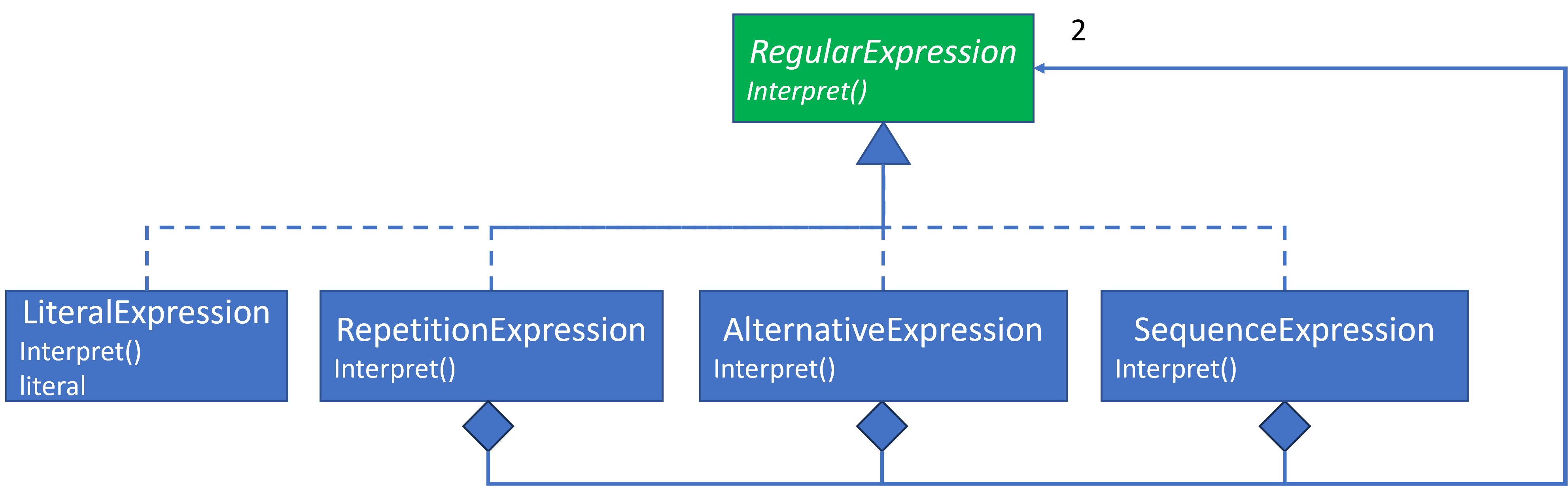

The Interpreter pattern uses a class to represent each grammar rule. Symbols on the right-hand side of the rule are instance variables of these classes. The grammar above is represented by five classes: an abstract class RegularExpression and its four subclasses LiteralExpression, AlternationExpression, SequenceExpression, and RepetitionExpression. The last three classes define variables that hold subexpressions.

Then they added this diagram. This is my is UML rendering of their OMT version. If interested, their version can be seen here:

Their class names don’t match the grammar terminology. They dropped the ’(‘ expression ‘)’ grammar rule from their design as well.

What the Gang of Four Skimmed Over

The GoF’s description of grammar mapping to design in their example is correct, but it is sparse. Here is my interpretation of the mapping from grammar to design:

- Each grammar rule will tend to be an interface or a class.

- Grammar rules based upon an OR, i.e.,

|, definition will be interfaces and the OR separated elements listed in that rule will implement it. This is an IS-A relationship. - Grammar rules based upon an AND definition will be classes. They will contain the elements listed in that rule. This is a HAS-A relationship.

- Explicit token elements, such as ‘(‘ or ‘)’ or keywords, are used for parsing, but they won’t be in the design. The token elements are road signs that help the parser identify where rules start and end and verify that parsing is on track.

Here is where the elegance emerges:

- Once you have a few stable grammar rules, even if the grammar is not complete, the initial design emerges based upon the bullets listed above.

- This is an initial design, and additional refactoring may be desired.

- The grammar inspired design will adhere to good OO design principles by default, such as:

- The design will be modular.

- Each interface and class will be relatively small and manageable because it will only focus upon a single responsibility.

- Classes will tend to depend upon interfaces, not other classes. And those dependencies will be limited in number.

- There will not be any circular dependencies.

- Each class can be easily unit tested.

- The design is maintainable. Due to the modular nature of the design with interface separation, updated or newly added grammar rules and their corresponding design components will tend to have minimal impact upon existing grammar rules and their design components.

Grammar to Design via Use Case

The following sections will show how the Rational Expression Evaluation Grammar leads to a design.

Grammar

I introduced the Rational Expression Evaluation Grammar Rules in the previous blog.

Here’s a copy with OR/AND and IS-A/HAS-A Relationship comments:

Statement ::= Assignment | Expression // OR Rule/IS-A Relationship

Assignment ::= Identifier = Expression // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

Expression ::= Identifier | Rational | AddOperation | SubtractOperation | MultipleOperation | DivideOperation // OR Rule/IS-A Relationship

Identifier ::= AlphaNumbericValue // Neither AND or OR relationship. More on this later.

Rational ::= Integer | Fraction | MixedFraction // OR Rule/IS-A Relationship

Fraction ::= Integer / Integer // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

MixedFraction ::= Integer Integer / Integer // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

AddOperation ::= + ( ExpressionList ) // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

SubtractOperation ::= - ( Expression, Expression) // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

MultiplyOperation ::= * ( ExpressionList ) // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

DivideOperation ::= / ( Expression, Expression ) // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

ExpressionList ::= Expression [, Expression]* // AND Rule/HAS-A Relationship

Design

The grammar rules will generate the first design. I have provided several design refactoring considerations as well.

First Design

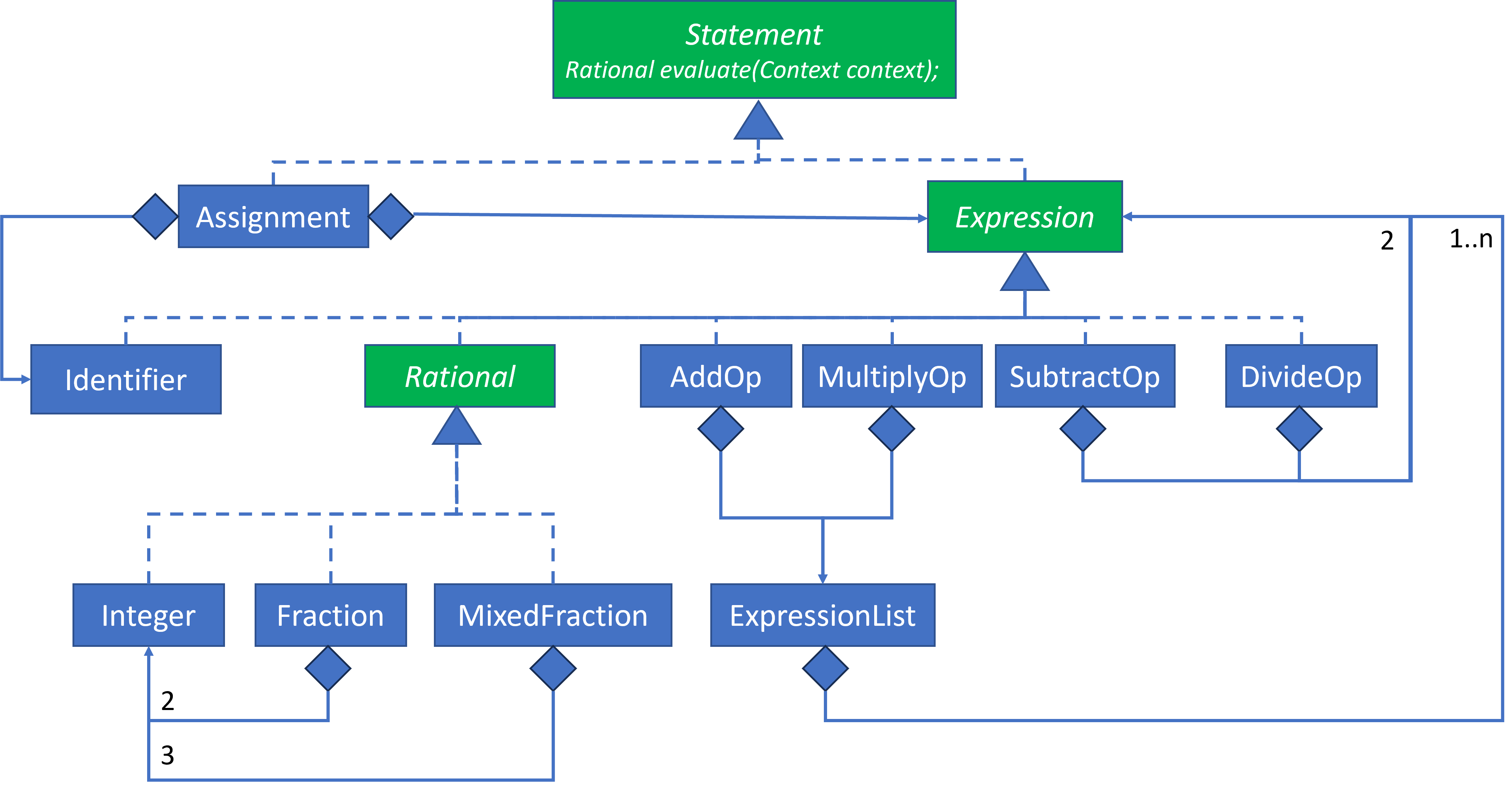

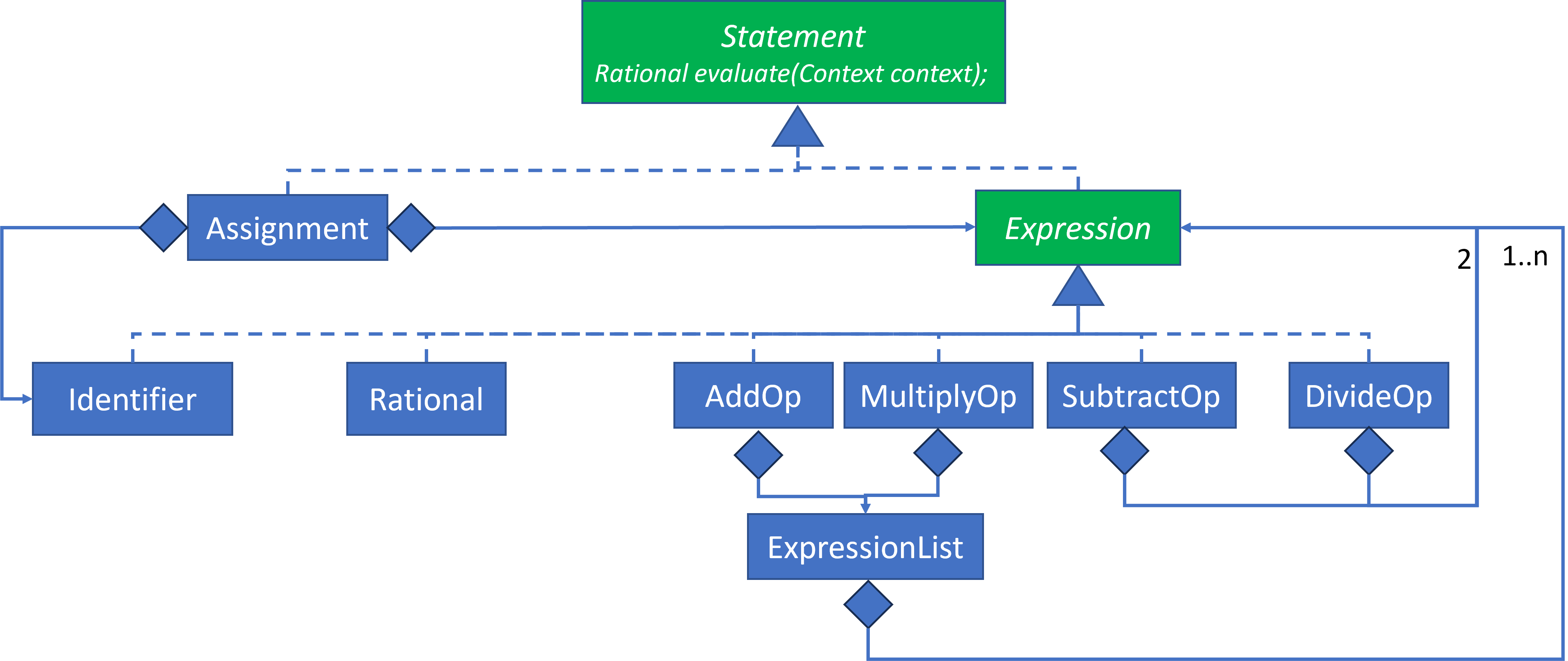

The following is a literal application of the mapping based upon the grammar rules above:

I started with the first rule, Statement, and I mapped the remaining grammar definitions into interfaces and classes one by one. It took only a few minutes, and most of that time involved organizing the graphic elements for presentation.

Recall that the implements triangle represents the IS-A relationship. The contains diamond represent the HAS-A relationship.

Technically there is a circular reference in the diagram. It’s quite subtle, and it didn’t occur to me until I was thinking about the design in the car while running a few errands several days after having drawn it up. There’s a relationship without a relationship line or arrow. Statement returns a Rational. Statement has knowledge of and sort of depends upon Rational only in the sense that it returns it. It does not process it. However, each concrete class will have knowledge of it, but that’s okay, since each concrete class derives from Statement. If I were to remove Rational from Statement, then the concrete class knowledge would disappear as well.

I’m going to keep this in the design. It’s declaration dependency, not functional dependency. Rational is a core domain concept. One would expect it to be a bit more prominent. Is Rational a public concept that requires a private implementation, or is it a private concept that’s been leaked in the abstraction? I’m not sure. It may not matter. The entire design is in support of the evaluator DSL, so none of these classes will be accessible outside of the DSL framework. I’m also not sure if these are legitimate reasons or whether I’m just Rationalizing my design decision.

Second Design

While this is the start of the design, it might not be the end of the design. There can be multiple grammars for the same DSL, and some may lead to a better design than others.

This is your DSL. Modify the grammar or the design as needed. You have the freedom to enhance grammar or design that you may not have with a General-Purpose Language grammar or design.

I haven’t started any implementation yet, but I’ve been thinking about how I might implement some of these classes. While the Rational grammar rule made it easy to document the three forms of a rational number:

- Integer as: Integer

- Fraction as: Integer / Integer

- Mixed Fraction as: Integer Integer / Integer

I don’t know if I necessarily need a class for each. I think I can implement Rational as its own class that supports these concepts without requiring these additional classes.

This refactoring transforms Rational from an interface to a class, and the derived classes disappear. The design is a bit smaller. I know that this refactoring update won’t affect the rest of the design, since nothing else in the design depends upon Rational or its previous Integer/Fraction/MixedFraction classes.

I’m planning for the parser to identify the tokens for all three forms of a Rational and pass a String of those forms as a constructor argument to the Rational class. The constructor will do additional specialized parsing on the three forms and construct the Rational instance accordingly.

Third Design

I’m not 100% pleased with the Add, Subtract, Multiple and Divide Op classes that popped out of the grammar-based design. I’ve implemented designs like this before, and I know there are going to be redundancies in the implementations as designed above.

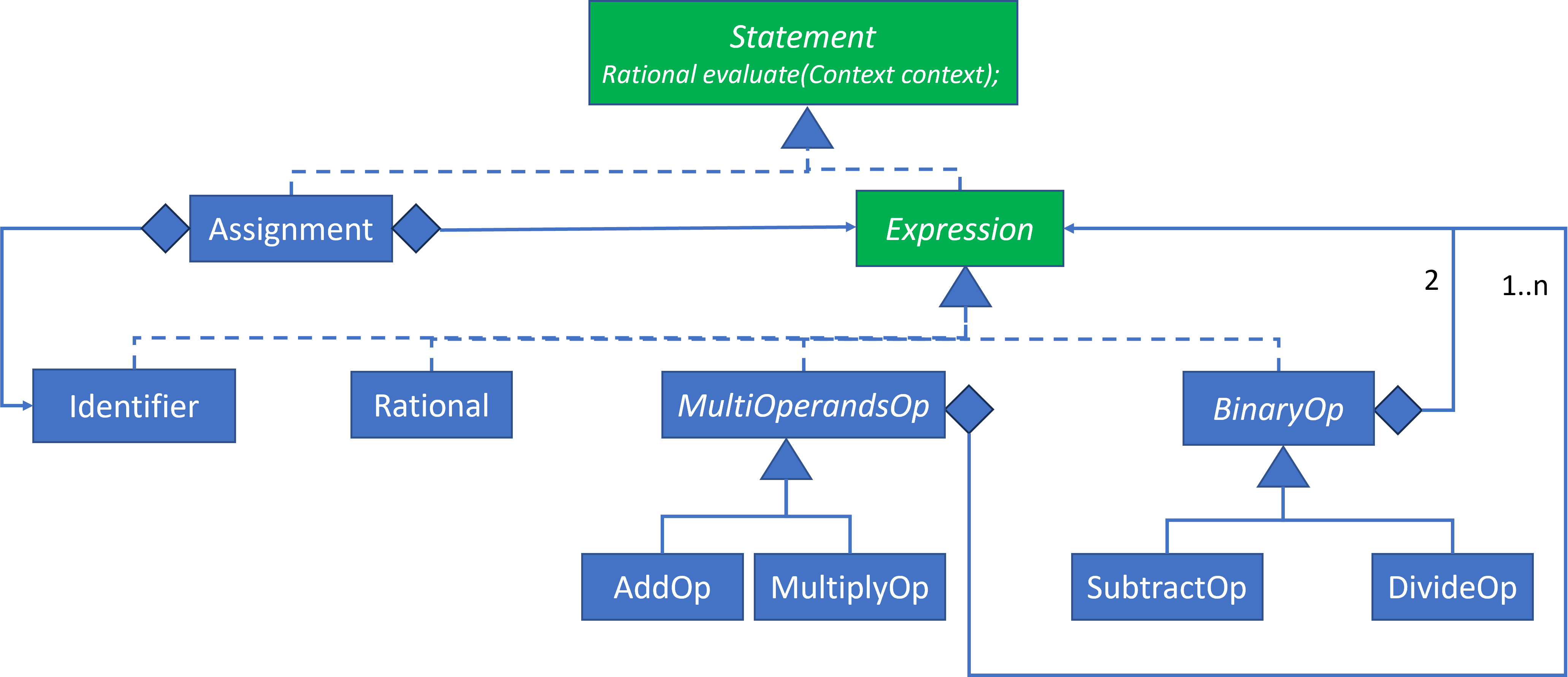

This refactoring adds two new classes MultiOperandOp and BinaryOp. They are abstract classes for operations with multiple operands and two operands respectively. The specific Operation (Op) classes will implement them:

I may be jumping the gun on this refactoring. We generally want at least three repetitions before refactoring like this, but The Rule of Three is more of a guideline than a rule that must be obeyed. I anticipate that most of the implementation will reside in the abstract base classes with minimum implementation in the concrete classes. I also anticipate the concrete class implementations for each of these abstract classes will be based upon the Template Method Design Pattern.

I’m also adding this refactoring to show that refactoring can add design elements that are not in the grammar. MultiOperandsOp and BinaryOp are not in the grammar, but they are design elements derived from the grammar.

Likewise, several grammar elements, such as Integer, Fraction, MixedFraction, and ExpressionList have been removed from the design since I think they can be more easily implemented within other classes rather than as their own standalone class. For example, ExpressionList is a List of some form. There’s no compelling reason for it to be its own class, when it can be a List of Expressions attribute declared within MultiOperandOp.

There is an alternative design for the arithmetic operations, which was mentioned to me during the review of this blog. All arithmetic operations could be BinaryOp classes, which would unify them even further and simplify the design, while still allowing for lists of additional and multiplications such as:

+(3, *(3, 4), 5)

However, it would take a bit more work in the parser to build the AddOp and MultiplyOp binary based objects to support lists of additions or multiplications. Everything is a tradeoff. I have decided to continue with the MultiOperandsOp design, but choosing the BinaryOp only design option would be equally valid. It’s more a matter of style and where one wants to manage lists of additions or multiplications.

Fourth Design

This fourth design idea won’t need a new diagram. It focuses upon the Identifier concept in the design. Even the grammar is a bit vague for Identifier:

Identifier ::= AlphaNumbericValue // Neither AND or OR relationship. More on this later.

Identifier will be used for state. The DSL has the concept of a variable, and the Identifier will be the handle for that variable. I anticipate that state will be stored in the Context as a map of String to Rational. The Identifier will be the key value for storing and retrieving state values from the Context.

The Identifier class will have a String identifier value that will return the Rational stored in the Context that contains that value.

The Assignment class gets more interesting. While the grammar shows that it HAS-An Identifier, I don’t think Assignment will contain an Identifier attribute in the implementation. I think the Assignment class will have a String identifier value that it will use as a key to store the Rational that’s evaluated from its Expression.

These implementation considerations are only in my head. I haven’t spelled them out in detail here; therefore, my design refactoring intent may not be too clear. My intent should make more sense when I present the implementation of the classes in the design in the next blog, Interpreter Design Pattern - Design to Implementation.

Redesign Conclusion

Design refactoring is the perfect time to do a lot of thinking and coming up with alternative ideas. Any change is simply a modification to a drawing tool. There’s almost zero sunk cost at this point.

If I find that my implementation ideas don’t work out, I can easily revert to a previous design or modify the existing one. I may find that some of these design ideas are wrong and require modification. That still should not be a major issue since the design is modular and modifications in one area won’t tend to have much of a ripple effect upon the others.

Design to Grammar

I’ve been presenting Interpreter as a process of Domain => Domain-Specific Language => Grammar => Design => Implementation. In practice, the process may not be discrete steps with handoffs like runners passing the baton. The journey from Domain to Implementation may progress in bits, possibly with all stages having active work at the same time.

And the process is not necessarily a one-way street. You might have a design first, and then you may want to see if it maps back to a grammar, even if you never intend to create a DSL. If a design doesn’t map to a grammar cleanly, then maybe the design might need some additional refinement.

The design-to-grammar exercise could be an additional means to confirm or clarify a design. Even if you don’t want to use grammar notation, transforming the design into sentences with IS-A and HAS-A phrasing will help indicate if it still makes sense.

Summary

Grammar elements map to design elements resulting in a modular and well-structured design. I feel this is the most elegant aspect of the Interpreter Design Pattern, and the GoF didn’t give it enough attention.

Additional refactoring may be applied to the grammar-generated design, which it should accommodate well due to the design being modular and well-structured.

I feel the Interpreter Design Pattern is the apex of the Design Pattern Principles:

- Program to an interface, not an implementation

- Favor object composition over class inheritance

The next blog, Interpreter Design Pattern - Design to Implementation, will feature the design’s implementation.

References

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

See: Interpreter Design Pattern Introduction/References.