Working Effectively with Legacy Code

… with all due respect to Michael Feathers in stealing his book title and a lot of his ideas for this blog

Introduction

Have you ever hesitated before touching a piece of code, fearing it might break everything? That’s the reality of working with legacy code.

I wrapped up the first part of my Automated Testing series primarily focused upon Test-Driven Development (TDD) and Behavior-Driven Development (BDD).

BDD and TDD are great practices to drive and shape a new implementation. However, many software developers maintain existing legacy code more often than they write new code. Since BDD and TDD practices focus upon writing tests before implementing the code, and legacy code has already been implemented, these practices, by definition, cannot support legacy code.

However, we can use concepts from BDD and TDD to help us maintain legacy code.

What is a Legacy?

Lin Manuel-Miranda had Alexander Hamilton ponder the meaning of legacy in Hamilton: The Musical with:

Legacy. What is a legacy? It’s planting seeds in a garden you never get to see.

Legacy tends to have positive connotations. It’s passing something valuable to the next generation. However, legacy code tends to have negative connotations.

Planting a seed in a garden isn’t enough to ensure a valuable legacy. One must nurture and maintain the garden by watering it and keeping it free of weeds and pests. All too often, legacy code isn’t well maintained.

I’m generalizing a bit, but legacy code tends to:

- Have large classes

- Have long methods

- Have deep nesting

- Have years of undocumented user-requested patches

- Have little nuggets of important and hidden behaviors that have long since been forgotten

- Depend upon many other software elements, often external dependencies

- Lack refactoring or redesign throughout its lifecycle

- Lack separation of concerns and appropriate levels of abstraction

- Lack automated tests

I do not wish to overly malign legacy code. We do not know what pressures the developer was under, nor do we know the experience level of the developer when the legacy code was implemented. No one sets out to create legacy code.

Regardless of the state of legacy code, it has one critical characteristic: Legacy code is the reason why many developers receive a regular paycheck.

Legacy Code’s Legacy

For all its maintenance issues, legacy code tends to work. It’s battle tested everyday by our best and most expensive testers — our users. If a serious problem is encountered by users, they tend to report it.

Given that our paying customers depend upon working legacy code regardless of its maintainability, we mostly want to leave working code well enough alone. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

We don’t always have the luxury of letting sleep dogs lie when it comes to legacy code. Sometimes a user unveils a dormant bug that’s been lurking in the code for years. New feature requests may require us to update legacy code.

Few things strike fear in the hearts of developers more than being assigned a ticket that forces them to descend into the bowels of unfamiliar legacy code.

Working Effectively with Legacy Code

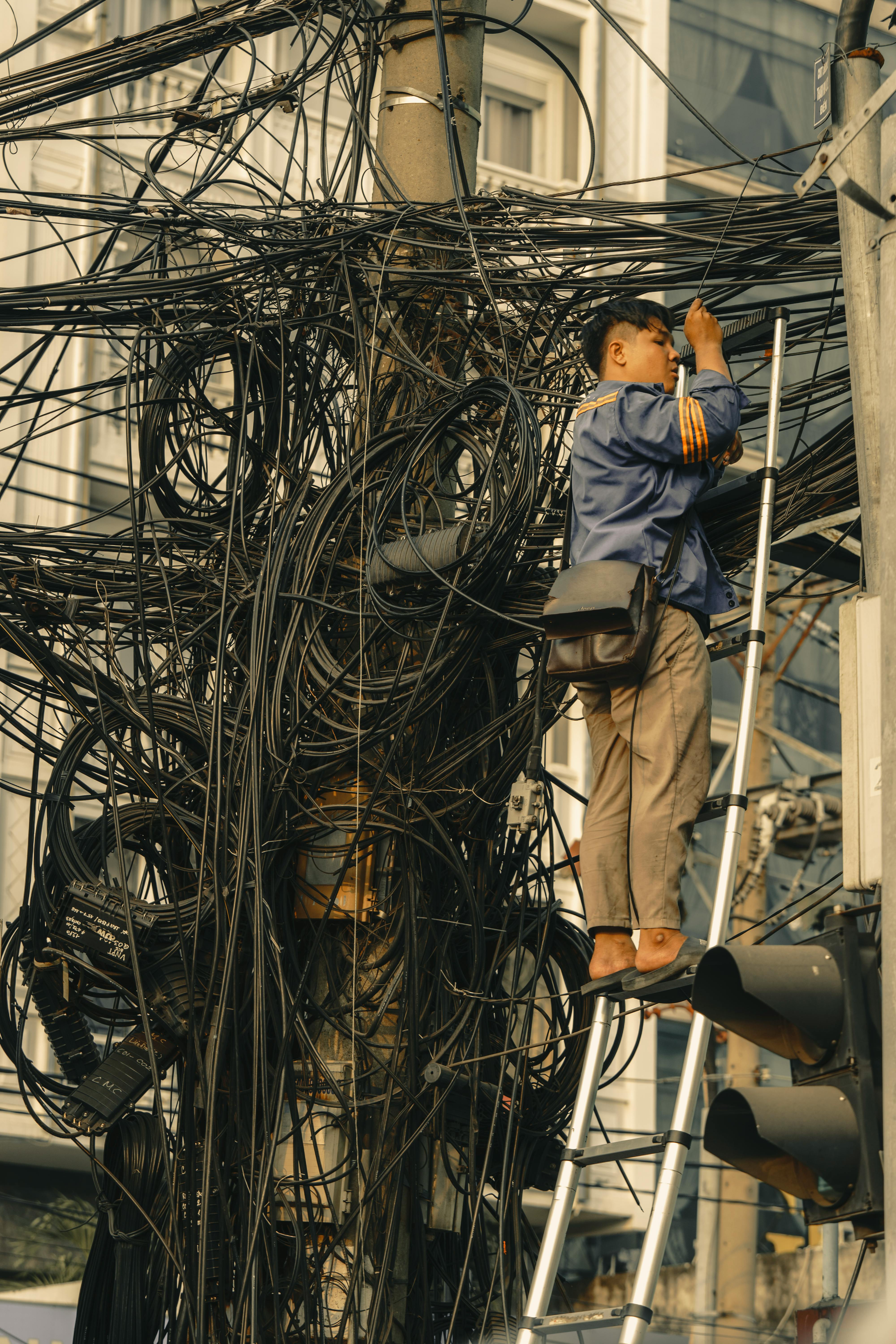

Working with legacy code is challenging. The implementation may be opaque. Many behaviors may not be well understood or documented. The challenge isn’t so much in updating legacy code to support new or updated behaviors. The challenge is in doing so without breaking any existing behaviors that the user depends upon. Updating legacy code can feel like the software equivalent of being on the bomb squad and hoping that you don’t cut the wrong wire.

Michael Feathers provided a glimmer of hope with his book: Working Effectively with Legacy Code. I briefly referenced his book in The Conversion of a Unit Test Denier. Here’s an excellent summary of the key points of book by Nicolas Carlo.

Feathers contends that all too often developers rely upon the edit and pray process when updating legacy code. Modify legacy without understanding the dependencies, and how likely are you to break something? Though a bit dated, this 2012 paper, SOFTWARE DEFECT ORIGINS AND REMOVAL METHODS by Capers Jones states that the odds of a modification introducing a new bug can be as high as 25%. He calls these bad fixes:

Bad fixes are inversely proportional to cyclomatic complexity, and also inversely proportional to experience. Bad fixes by a top-gun software engineer working with software with low cyclomatic complexity can be only a fraction of 1%.

At the other end of the spectrum, bad fixes by a novice trying to fix a bug in an error-prone module with high cyclomatic complexity can top 25%.

Feathers advocates cover and modify, where developers cover the legacy code with tests, and then modify it with the confidence that existing behavior hasn’t broken unintentionally.

Legacy code doesn’t tend to have tests. Feathers even defines legacy code as code without tests. Unfortunately, code that was implemented without tests tends to be obdurate to having tests added to it later.

We can’t easily add tests to obdurate code, until we’ve updated the code to make it more accommodating to being tested. But we can’t modify legacy code confidently unless we have tests to ensure we haven’t broken something. We’re in a Catch-22 situation.

Feathers devotes the first 20% of his book to convincing developers to add tests to legacy code. He devotes the remaining 80% to relatively safe refactoring techniques one can apply to obdurate non-tested code safely making it more accommodating to tests.

I’m not going to sugar coat this. Adding tests to legacy code is hard work. Sometimes you can spend a day or more and your only progress is adding coverage to a handful of lines of legacy code.

TIP: If your unit tests are nasty and/or difficult to implement, the issue is probably not the test. It is an indication that code those tests confirm is nasty and in need of refactoring and/or redesign.

That previous TIP is going to haunt you. Legacy code wasn’t created using TDD. It is probably nasty and in need of refactoring and/or redesign. The unit tests will be nasty and difficult to implement, at least at the start. Well designed and implemented code tends to have straightforward test cases. Therefore, test cases that are messy, confusing, complicated, etc. may be an indication that the code they confirm is messy, confusing, complicated, etc. This could be an indication of a redesigning opportunity, but I’m getting a bit ahead of myself.

Seams

One of my previous officemate’s father was an old-school tailor. He could deconstruct a suit into its individual parts and reassemble them into a customed fit for his clients. He didn’t disassemble the suit by cutting randomly into the cloth. He deconstructed the suit at its seams.

Code is most easily tested along its seams. Seams allow us to disassemble and isolate pieces of code much like my officemate’s father was able to disassemble and isolate the pieces of a suit. Once code is isolated from its dependencies, then it can be more easily tested.

Seams reside along boundaries and tend to be Stable or Fixed Elements within the code, such as interfaces and method signatures. Ideally, seams lie along Natural Boundaries.

Mocking Frameworks

Working Effectively with Legacy Code was published in 2004, and to the best of my knowledge there have not been follow up editions. Most of Feathers’ refactoring techniques require manual intervention to add seams. However, in the subsequent two decades, different test frameworks have arisen. Mockito is a popular one for Java.

I advocate understanding the underlying mechanisms before using mocking frameworks as I described in Write Your Own Test Doubles Or Use A Framework?.

However, I have used Mockito to introduce seams. My last project provided wrappers for MongoDB calls, which worked nicely, except that the wrappers were static methods, which tightly coupled the application code to MongoDB. Making matters worse, static methods are very obdurate to seams. An Adapter design would have made testing much easier.

Mockito 3.4.0 provided the ability to inject Test Double behaviors into static methods without having to touch the implemenation as described in this Mockito Static Method Tutorial. I was able to break the tight static method coupling with this technique, even if it is a bit clunky to set up.

Even though Mockito provided this ability, the tutorial adds this caveat:

Generally speaking, some might say that when writing clean object-orientated code, we shouldn’t need to mock static classes. This could typically hint at a design issue or code smell in our application.

Why? First, a class depending on a static method has tight coupling, and second, it nearly always leads to code that is difficult to test. Ideally, a class should not be responsible for obtaining its dependencies, and if possible, they should be externally injected.

So, it’s always worth investigating if we can refactor our code to make it more testable. Of course, this is not always possible, and sometimes we need to mock static methods.

Legacy Code Lacks Seams

Over time, legacy code accumulates small, incremental changes, gradually expanding without regard for maintaining clear boundary seams. It’s the lack of seams in legacy code that makes it obdurate to tests. To make legacy code more test accommodating, we may need to add seams so that we can isolate pieces of code making them more manageable for testing.

Extract Method is one of the most valuable refactoring tool to safely introduce seams to legacy code. The steps of extract method are basically:

- Select a block of statements in the code that ideally encapsulates a single intent or responsibility.

- Copy those statements into their own newly named method where the new name indicates the intent or responsibility.

- Replace the original block with a method call to the new extracted method.

There are several advantages of Extract Method:

- Larger methods are decomposed into smaller more manageable methods.

- New method names provide additional context.

- Extracted methods introduce seams making the code more accommodating to tests.

Extract Method is a refactoring tool in most IDEs. These refactoring tools manage all the details except the name choice of the new method. If the new method’s intent is unclear, then choose a name that best describes what it’s doing, even if the name describes the method’s implementation. The name can be updated as the code reveals itself, and intent is better understood.

IDE tools usually declare extracted methods as private by default. This is usually what we want when refactoring code that already has test coverage. However, in the case of introducing seams to legacy code for testing, we will probably need to declare the extracted method as package-private. I’m using this Java term to convey that the method has scope to code within the same namespace. Test code is often in the same namespace as the implementation being tested, which allows the test code to access the package-private method for testing without exposing the method externally as public.

A package-private declaration allows us to:

- Override the extracted method with a Test Double

- Test extracted methods separately in isolation

Though a package-private declaration couples the tests with the implementation making the tests a bit more brittle, we may need to do this until we have added sufficient test coverage.

I described how Suril and I introduced a package-private seam to code via Extract Method to make testing easier.

Characterization Tests

Introducing seams allows us to isolate pieces of the legacy code so that they can be tested. But what are we testing? TDD and BDD start with the assumption that you know the expected behavior, but that may not be the case for legacy code. We may have a notion of some of the behavior, but there’s a good chance we don’t know all the behavior that’s lurking in legacy code.

Feathers describes Characterization Tests in his book. Characterization Tests look like TDD/BDD tests since they still maintain the Give/When/Then format, but that’s pretty much where the resemblance ends.

Characterization Tests differ from TDD/BDD tests in that TDD/BDD tests specify behavior, whereas Characterization Tests reveal existing behavior. Since users execute legacy code regularly, any behaviors revealed through Characterization Test will be correct, dead code or unobservable by the user. The goal of Characterization Tests is to lock down existing behavior so that additional refactoring can be done to clean up the code making it maintainable without breaking any of the existing behavior.

Characterization Tests reveal behavior after the implementation. How do we create a test to reveal behavior when we don’t know what behavior is being revealed? We will need to reference the implementation.

Here are some suggestions when writing Characterization Tests:

- Focus upon one public method at a time.

- Write a test that calls the public method in the When section of the test.

- The test will probably throw an exception because a dependency has not been initialized. NOTE: This could be a complete test as is since it reveals that the code throws an exception with uninitialized dependencies, but that’s probably not the main concern yet.

- Declare and inject Test Doubles in the Given section of the tests to resolve dependencies. This may require more seams via method extraction.

- Once the test no longer throws exceptions, focus upon the Then portion of the test by adding Assertions and Verifications. For example, if the public method returns a String, then add an assert declaring that the expected return value is something outrageous, such as: Fred Flintstone. This will fail, but it will also identify the actual String that was returned by the legacy code. Replace Fred Flintstone with what the public method returned. This has revealed the legacy code’s behavior. It’s documented in an automated and repeatable test.

- Run the test with code coverage activated. This will identify the lines of code that were executed in test. Put on your detective hat and look for other behaviors that can be asserted or verified. Add them in the Then section of the test.

- While the Characterization Test documents revealed behavior, you may still not understand what is being revealed. You may not be able to provide a test name that indicates behavior specification or intent. Don’t be concerned about this. Choose a name that describes what the test is doing instead.

- Repeat with a new test until you the tests cover as much of the scoped legacy code as possible.

Characterization Tests are an exploratory tool. We use them to reveal behavior, not define it. We never know when all the behaviors have been revealed. Creating enough Characterization Tests is a judgement call. Code coverage is probably our greatest tool in determining if we have enough Characterization Tests. When statements have no coverage, then we know that there is more work to do. Complete coverage does not guarantee that all behaviors have been covered, but uncovered code is a clear indication that there’s uncovered behavior. Mutation Testing is another tool that can aid in knowing when you have sufficient tests.

Characterization tests are a behavior exploration, discovery and revealing technique.

Iterate All Combinations

Most legacy code I’ve encountered was a Big Ball of Mud. Methods contained too many paths of execution through the code to create individual Characterization Tests for each combination. In these cases, I would design a Characterization Test that would iterate through all possible configuration combinations in the method being tested.

Take this simple method as an example of iterating through all combinations. While this is a small, controlled case, imagine a similar piece of code—only 100 lines long, deeply nested up to five levels, and juggling ten independent variables, all without clear context.

public static String doThis(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

String returnValue = "";

if (a && !b) {

returnValue += "Fizz";

if (c) returnValue += "Buzz";

} else if (b || c) {

returnValue = "Beep";

if (a || b) returnValue += "Boop";

} else {

returnValue += "Splat";

}

return returnValue;

}

Configurable entities usually include Test Double behaviors and arguments with multiple behaviors and parameter values with each iterating through as many equivalence partitions as I can think of. The test consists of nested for loops for each configurable entity, and then at the deepest nesting, the configurable entities are passed as arguments to a driver method which contains the test in Given/When/Then format. The driver method initializes the Test Doubles in the Given section with the passed parameter values and calls the public method being tested with passed parameter values as well.

It doesn’t take too many nested configurable entities iterating through their equivalence behavior partitions before the number of calls to the test driver becomes huge. It was common for the number of test driver calls to reach hundreds or thousands of potential configuration iterations. Rather than completing in seconds, these tests could take minutes — many minutes. It was the price I was willing to pay to ensure that every possible path was being executed, even if I knew that many configurations were redundant.

While the test driver method is organized in the Given/When/Then structure, it doesn’t tend to look like the traditional unit tests. Traditional unit tests tend to be straight to the point. Test driver methods are closer to a template for all possible configuration combinations. Test driver code includes more nuance and logic to cover all possible combinations.

I usually started the test driver without parameters where the configuration resided in the test driver itself, like it does in traditional unit tests. Then I’d declare a configurable element in the test driver method signature and iterate through the possible values in the test that delegated to it. One of the configuration argument values would cause the test to fail on one of its iterations. I would modify the assertion and verification logic in the Then portion of my tests to accommodate different configuration values.

I added one more configurable entity at a time until all possible configuration combinations were covered. This often required more sophisticated logic in the assertions and verifications.

The test driver may have to accommodate thousands of configuration combinations. It may take minutes before they’re all handled correctly. The test driver may iterate hundreds of combinations before failing on one of the configurations, but which one failed?

I often added a print statement at the top of the test that logged the parameter values to the console. If a combination failed, then its parameter values would be the last ones in the log.

Here’s an example of a test and test driver that iterates through all possible combinations of doThis. NOTE: There is no need for Test Doubles for this test, since doThis has no external dependencies:

private static void testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) throws Exception {

System.out.format("doThis(a=%b, b=%b, c=%b)\n", a, b, c);

// Given-When

String result = LegacySoftwareUnderTest.doThis(a, b, c);

// Then

assertEquals(getExpectedReturnValue(a, b, c), result);

}

// NOTE: This logic emerged one test iteration at a time until all combinations were passing.

private static String getExpectedReturnValue(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

if (a && !b && !c) return "Fizz";

if (!a && !b && !c) return "Splat";

if (!a && !b) return "Beep";

if (!b) return "FizzBuzz";

return "BeepBoop";

}

public static void testDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations() throws Exception {

for (Boolean a : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

for (Boolean b : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

for (Boolean c : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(a, b, c);

}

}

}

}

When there were thousands of iterations, it might also take a long time to reach the failing combination. When that occurred, I would create a separate method that called the test driver with the failed combination so I could more easily isolate it. run the failing combination immediately and focus upon getting it to pass.

Here’s an example of running the test driver for one specific iteration, which isolates the combination, a=true, b=false, c=false, if it were failing:

public static void testSpecificCombination() throws Exception {

testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(true, false, false);

}

Test drivers tend to replicate the implementation to some degree. I always tried to keep the test driver’s implementation different from the tested code. In a way, the test driver was rewriting the code being tested without having to touch the code being tested. Hidden behaviors would sometimes emerge within the test driver.

Iterating tests are brittle. I often felt a little dirty in creating them. They provided peace of mind that I had all possible paths covered when I didn’t understand the code, but they could easily break as I refactored the code, which I’ll address shortly.

Updating Legacy Code

Before working on the desired modification, that is, the bug or the new feature, you may want to consider refactoring the current legacy code first.

Refactoring

Refactoring is changing the structure of the code without changing its behavior. We may want to refactor legacy code before making updates to make it easier to accommodate the updates.

For each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change. — Kent Beck

Since doThis has coverage, I refactored it with the confidence that if my refactoring was incorrect, then one of the iterating tests would catch it.

No intent emerged during refactoring, since there wasn’t any original intent. However, the refactored code is less complex. If there had been intent in the original code, I suspect it would have emerged:

public static String doThis(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

if (b) return "BeepBoop";

if (a) return c ? "FizzBuzz" : "Fizz";

if (c) return "Beep";

return "Splat";

}

If I were making a modification to doThis, I think I would have more confidence in updating this refactored version than the original version listed previously.

Adding tests and refactoring legacy code align with these two practices:

- The Method Use Rule - This rule helps you figure out which legacy code requires test coverage. Before you use a method in a legacy system, check to see if there are tests for it. If there aren’t, write them. - Michael Feathers

- The Camping Rule - This rule helps you determine what to do in that legacy code. Always leave the code cleaner than you found it. - Uncle Bob Martin

Legacy code won’t fix itself. A code base with years or decades of legacy code may require additional effort to address code rot abatement. You cannot make the system perfect. You cannot make it good. What you can do is make it less bad. Focus upon steering it into the right direction, applying The Camping Rule when we can. Eventually as we steer in the right direction, the existing code base will become cleaner and less brittle.

Refactoring can be rewarding. You will find bugs lurking in the code that no one spotted before. You will bring order to chaos. You may even take a tangled mess of code and convert it into something beautiful and elegant.

Characterization Tests Are Brittle

The more you refactor code to convey its intent, the more likely you are for the Characterization Tests to break, because they are brittle. Characterization Tests are brittle, since they are shaped by the implementation and not by behavior. As intent and behavior emerge, write tests that specify the emerging behavior and retire the characterization tests.

Characterization Tests provided initial coverage, but they may only be steppingstones in the process. For example, iterating tests for doThis might be replaced with:

doThis_ReturnsBeepBoop_WhenBIsTrue()doThis_ReturnsFizzBuzz_WhenAAndCAreBothTrue()doThis_ReturnsFizz_WhenAIsTrueAndCIsFalse()doThis_ReturnsBeep_WhenCIsTrueAndAIsFalse()doThis_ReturnsSplat_WhenAAndBAndCAreFalse()

… then make the easy change

Once the legacy code is covered, and refactored a bit, you can start working on the desired modification. Regardless of whether this is to fix a bug or add a new feature, you can follow a more traditional TDD/BDD process.

For a bug, create a test that replicates the incorrect behavior. Then update the test so that it defines the desired behavior, which will fail. For the new behavior, create a behavior specifying failing test.

Now that we have coverage, refactored code and failing tests for the task at hand, we are much closer to a TDD/BDD scenario. We can modify the legacy code to get the tests to pass and refactor the updated code once all tests pass.

Intent and behavior may start to emerge through refactoring. Refactoring may take you a long way toward making the legacy code more comprehendible, but it will only take you so far. A refactored implementation may start to suggest better design options, which may involve reorganizing classes.

Since unit tests tend to specify behaviors within classes, any class redesign will reorganize where those behaviors reside. The unit tests may need reorganization as well so that they specify the behaviors in the redesigned classes. This may require new tests, removing existing tests, splitting existing tests, etc.

Hey. This doesn’t look right.

Hidden behaviors and intent may start to emerge through refactoring. This will make the legacy code more maintainable.

Sometimes the behaviors revealed may not look correct. A hidden bug may have been exposed.

Here’s a situation that I encountered while working on some legacy code.

The feature managed a set backend batch tasks. A background manager processed a set of tasks each with a unique integer identifier. The batch manager identified the tasks that passed, failed and were interrupted while being processed. It recorded this information and returned it in a BatchResults object, which was a straightforward class that looked something like this:

class BatchResults {

private List<Integer> passed = new LinkedList<>();

private List<Integer> failed = new LinkedList<>();

private List<Integer> interrupted = new LinkedList<>();

public void addPassed(int id) {

passed.add(id);

}

public void addFailed(int id) {

passed.add(id);

}

public void addInterrupted(int id) {

passed.add(id);

}

public int getPassed() {

return passed;

}

public int getFailed() {

return failed;

}

public int getInterrupted() {

return interrupted;

}

}

I spun my chair around to address my teammate who sat behind me and asked, “Hey, Ron. Can you look at this? It doesn’t look right to me. The failed and interrupted ids are being added to the passed List.”

“Oh, that’s not right,” Ron replied, “Gee, I wonder how many failed and interrupted ids have been incorrectly recorded as passed.”

BatchResults didn’t have any unit tests. I added failing tests for the failed and interrupted scenarios and then fixed the code.

This was an obvious error, and Ron had confirmed it. But sometimes the legacy code may reveal behavior and intent that looks questionable, and it’s not as obvious as the error in BatchResults. Do not fix this code, since it may not be broken. Many of us don’t have the domain knowledge to make that call within legacy code. Remember the old adage: That’s not a bug. It’s a feature. You may fix something that a customer is depending upon.

However, we don’t just ignore it either. Here’s my recommendation:

- Create a passing test that demonstrates the questionable behavior but give it a name that questions that behavior. For example, if Ron didn’t confirm the

BatchResultserror, I would have created a test with the name:getPassed_ReturnsIdsAddedViaAddFailedAndAddInterrupted_SHOULD_IT. AddingSHOULD_ITchange the indicative form of the test name into a question. I would have also added some comments in the test declaring why I questioned the revealed behavior. - Create a ticket just that describes the questionable behavior, why you question it, and reference the

SHOULD_ITtest.

Hopefully the ticket will be assigned to someone who has more domain knowledge than you. If the behavior is correct as-is, then the only update needed is to remove SHOULD_IT from the test name as well as any questioning comments, and now we have a test that declares that the behavior is correct, even if it might still look a little questionable.

If the behavior is incorrect, then a new failing test that defines the correct behavior should be created. The implementation can then be modified to pass the new test, which will cause the previous passing SHOULD_IT test to fail. The SHOULD_IT test can then be removed.

Let’s return to BatchResults briefly. It didn’t have any unit tests, but should it? Was this an oversight by the developer who wrote BatchResults? There’s a unit testing community that believes that it’s a waste of resources to test simple code. Devote your efforts toward covering more complex code. Accessors are a prime example where you often don’t see test coverage. Accessors will be tested indirectly as they are invoked in code that is unit tested.

I’m of the opinion that any code that’s created by hand should be tested. While BatchResults is not complex, its error lurked there for months. While I don’t know how the error was introduced, I’d be willing to bet that addPassed(int id) was copied-and-pasted as addFailed(int id) and addInterrupted(int id) and only the method name was updated. The copied implementations were not updated and failed and interrupted ids were being recorded as having passed incorrectly.

“It doesn’t need to be unit tested,” I can hear the developer say, “It’s so simple, that it’s obviously correct.” It only looked correct, because previous code reviewers saw what they thought should be there rather than what was actually there. My fresh eyes spotted the obvious error.

“If there had been unit tests for the Batch Processor, then it would have found the bug for sure,” some might argue. That’s probably true; however, there were no unit tests for the Batch Processor either. And had there been unit tests for the Batch Processor, which would have failed due to the error in BatchResults, how long would it have taken anyone to think to look at the BatchResults class as the source of the error? How much time would have been spent searching for the error in the Batch Processor that was not there?

I wrote unit tests for BatchResults in about five to ten minutes. Would that have been less than the time it would have taken to debug any Batch Processor tests? Would it have been worth the investment as compared to having missed failed and interrupted ids several months?

I feel that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

A Necessary Evil

Characterization tests are useful tools when working with legacy code, but as I’ve pointed out above:

- They can be difficult to write.

- They can be implementation dependent and brittle.

- They can can be ugly.

- They become redundant and a liability once the legacy code has been understood, refactored and new behavior based tests have replaced them.

Because of their nature, they may be good candidates for code generation. I retired before I had an opportunity to experiement with this idea, so it’s still conjecture. I think worthy of investigation. Here’s a possible prompt:

I have some legacy Java code that I need to put under test. The goal is not to redesign or refactor the code right now, but to create characterization tests that capture the current behavior so I can safely make changes later.

Please:

- Analyze the given Java class or method.

- Identify observable inputs and outputs, including return values, exceptions, and side effects (e.g., state changes, file I/O, database calls).

- Suggest test cases that cover:

- Typical/expected inputs

- Edge and boundary conditions

- Error or exceptional cases

- Any unintuitive or surprising behavior that should be locked down

- Provide test code using JUnit 5 (with @Test, assertEquals, assertThrows, etc.).

- Ensure the tests capture and document the current behavior (even if it looks buggy or counterintuitive).

- Organize tests so that they are readable, naming them according to the behavior being tested (e.g., shouldReturnXWhenY).

Summary

Legacy code may seem daunting, but with the right strategies—automated testing, refactoring for testability, and leveraging seams—it becomes manageable. By taking a disciplined, incremental approach, developers can modernize code while preserving its reliability and reducing technical debt.

While time constraints and business priorities often make teams hesitant to refactor, small improvements—like writing tests before making changes—can significantly lower risk. Instead of viewing legacy code as a burden, treating it as an opportunity for steady enhancement ensures it remains a stable foundation for future development.

References

Here are some free resources:

- Wikipedia Legacy Systems

- Wikipedia Characterization Test

- Characterization Tests by Michael Feathers

- Refactoring.guru on Refactoring

- Extract Method by Refactoring.guru

- The key points of Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Nicolas Carlo

- Understanding Legacy Code: Change Messy Software Without Breaking It by Nicolas Carlo

- The Legacy Code Survival Guide: Add Features Without Fear by Nicolas Carlo summarizing Steven Diamente’s presentation of the same name. Presentation is embedded in the summary.

- Notes from Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Barry O’Sullivan, which I think provides a summary for each chapter of Working Effectively with Legacy Code

- 9 Techniques That Help You Safely Work With Legacy Code by SciTools

- Navigating Legacy Code: How I Used the Sprout Method to build a new feature by Sibin M S

- 9 Tips for Working With Legacy Code by Stuart Foster

- Legacy Code Rocks! - Landing page for a podcast and community devoted to Legacy Code concerns

- and for more, Google: Legacy Code

- and: Characterization Tests

Here are some resources that can be purchased or are included in a subscription service:

Complete Code Example

Here’s the complete Java code for the iterating tests. I haven’t used a test framework. You should be able to copy-and-paste the entire Java program into any Java environment and run it:

import java.util.*;

public class LegacyCode {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Test.test();

}

}

class LegacySoftwareUnderTest {

public static String doThisOriginal(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

String returnValue = "";

if (a && !b) {

returnValue += "Fizz";

if (c) returnValue += "Buzz";

} else if (b || c) {

returnValue = "Beep";

if (a || b) returnValue += "Boop";

} else {

returnValue += "Splat";

}

return returnValue;

}

public static String doThis(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

if (b) return "BeepBoop";

if (a) return c ? "FizzBuzz" : "Fizz";

if (c) return "Beep";

return "Splat";

}

}

class Test {

public static void test() throws Exception {

testSpecificCombination();

testDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations();

}

private static void testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) throws Exception {

System.out.format("doThis(a=%b, b=%b, c=%b)\n", a, b, c);

// Given-When

String result = LegacySoftwareUnderTest.doThis(a, b, c); // And also call doThisOriginal(a, b, c)

// Then

assertEquals(getExpectedReturnValue(a, b, c), result);

}

private static String getExpectedReturnValue(boolean a, boolean b, boolean c) {

if (a && !b && !c) return "Fizz";

if (!a && !b && !c) return "Splat";

if (!a && !b) return "Beep";

if (!b) return "FizzBuzz";

return "BeepBoop";

}

public static void testDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations() throws Exception {

for (Boolean a : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

for (Boolean b : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

for (Boolean c : Arrays.asList(true, false)) {

testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(a, b, c);

}

}

}

}

public static void testSpecificCombination() throws Exception {

testDriverForDoThisInAllPossibleCombinations(true, false, false);

}

private static void assertEquals(String expected, String actual) throws Exception {

if (!expected.equals(actual)) {

System.out.format("expected=%s, actual=%s\n", expected, actual);

throw new Exception();

}

}

}