Interpreter Design Pattern – Production Example

My Experience Using Interpreter on a Work Project

The Introduction

This blog completes the Interpreter Design Pattern series with the highlights of when I implemented the Interpreter Design Pattern the one time in my career.

The Spoiler

If you made it through my previous blogs, you’ll see a definite progression of Domain-Specific Language (DSL) to Grammar to Design to Implementation to Scanner/Parser.

It sounds great in theory, but as I listed in Bumper Sticker Computer Science and Software Engineering:

In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not. ― Attributed to many

Spoiler Alert: My Interpreter experience didn’t start with a Domain-Specific Language, but it eventually got there.

The Domain

I will feature a domain that wasn’t my project’s actual domain. They are conceptually similar, but the blog domain should be more familiar to a wider audience.

Imagine an automated package processing center, such as one used by United Parcel Service, Federal Express or DHL. Packages enter the processing center on an inbound loading dock. They’re routed through the center based upon address, priority, client loyalty program, etc. with their destination being an outbound loading dock.

The processing center’s automation is based upon a set of routing rules. My project was responsible for the implementation of the routing rules in our domain, but our domain’s routing rules were not for physical packages. Our domain routed messages, much like TCP Packets.

Our domain was so like an automated packaging processing center that we often used the package processing center as a metaphor in understanding and modeling concepts in our own domain. I can convey most of what we experienced with the automated package processing center domain without losing too much in translation.

The Requirements

I joined this software company just as the new project was ramping up. Our Project Manager (PM) described to our team its main features, which routed packages based upon a set of rules. Our PM presented the rules as slides in a PowerPoint presentation deck, which I assumed was what he had used in presentations with the customer.

There were about two dozen slides each in the form of an IF RULEs that were like the following:

If the Package:

Is High Priority

And Is Local Address

Then:

Route to Immediate Delivery Local Ground Transportation

If the Package:

Is High Priority

And Is Not Local Address

Then:

Route to Air Transportation

If the Package:

Is not High Priority

And Address is Local

Then:

Route to Filled-Truck Ground Transportation

If the Package:

Is not High Priority

And Address is Not Local

Then:

Route to Long-Haul Ground Transportation

I asked when we would get a formal requirements document with enumerated requirements. He responded that the PowerPoint slides were the formal requirements.

The two dozen routing rules were different combinations of the same basic routing concepts. Several thoughts came to mind:

- Were they correct and complete? I had my doubts. Turns out, those doubts were well founded.

- The rules, or at least their fundamental concepts, felt cohesive. I was concerned that a traditional implementation might distribute the rules in such a way that we’d obscure their cohesiveness.

- I had a gut feeling that flexibility might be needed even if the PowerPoint slide requirements were correct and complete. Would every processing center have the same set of routing rules? Might each need its own set of rules?

The Pitch

I thought about the requirements. The slide presentation didn’t give me a great sense of confidence. I modeled them to see if I could obtain a better understanding even if only for my own benefit.

The same phrases repeated:

- Is High Priority (and its negation)

- Is Local Address (and its negation)

- Route to Immediate Delivery Local Ground Transportation

- Route to Air Transportation

- Route to Filled-Truck Ground Transportation

- Etc.

I thought a composable design would accommodate what we needed. I understood the Interpreter Design Pattern, but only as it applied to UML class diagrams. I didn’t appreciate what the Gang of Four (GoF) were trying to convey when they referred to Language or Grammar. Therefore, I never had any thoughts of a DSL or Grammar when I dove headfirst into a UML class design.

I wanted a design that glued the repeating behaviors together easily. I wanted the design to be lightweight.

I sketched my initial design on a whiteboard in a conference room and presented it during a team meeting. To my surprise, my manager gave me the okay to move forward with it. I had been with the company for about 3 weeks at this point.

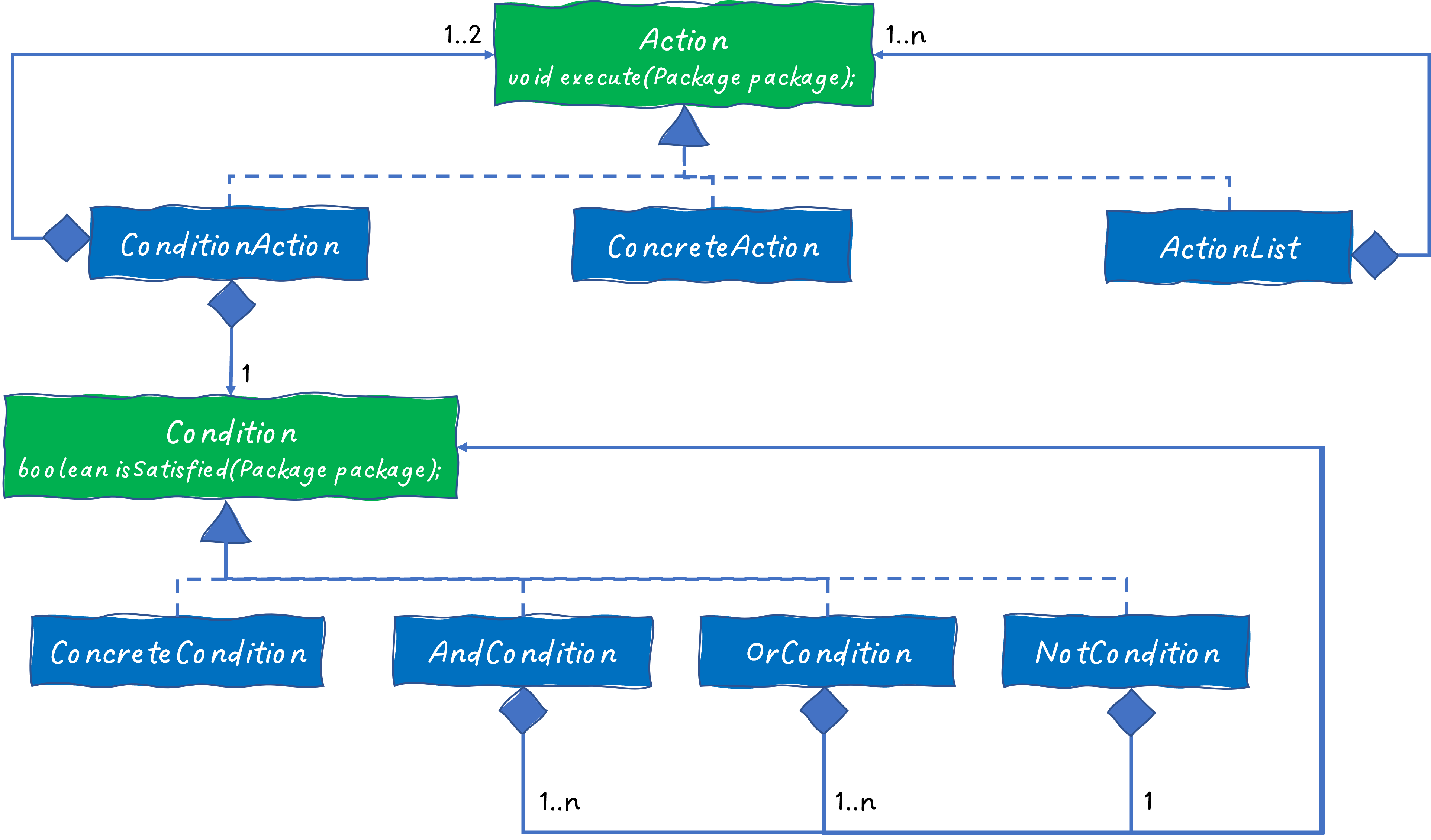

This design allows us to configure any Rule based upon a set of Actions and Conditions. Notice the direction of knowledge and dependency. Action and Condition are stable/fixed elements. The other classes are unstable/flexible elements.

Unstable/flexible can be added, modified, or removed without affecting the rest of the design. This is the same knowledge and dependency management benefits described with Hexagonal Architecture Knowledge and Dependency Management.

There are several design patterns tucked away in this design.

Action and Condition

Action and Command are examples of the Command and Strategy design patterns.

ConcreteAction

ConcreteAction is placeholder for classes that implement basic actions. There would be a ConcreteAction class declaration for each individual action behavior. ConcreteActions would be behaviors, such as:

- Route to Immediate Delivery Local Ground Transportation

- Route to Air Transportation

- Route to Filled-Truck Ground Transportation

There were more Actions than just transportation behaviors, but this list above should suffice as examples for now. A Route implementation was often a family of cohesive classes. Each Route behavior might require many classes with a substantial amount of code. I didn’t want a ConcreteAction class to contain those implementation details.

The ConcreteAction classes were often Adapters, which implemented Action and delegated to a class that did the routing. The Adapter Design Pattern allows the ConcreteAction classes to plug into the design above and delegate to Route classes. Since all knowledge and dependency flows away from Adapters, the design above has no knowledge of the Route classes, and the Route classes have no knowledge of the design above. They can be designed, implemented, and tested independently. The Adapter is the only class that needs to adjust when either the design above or a Route class has an impacting update.

A ConcreteAction implementation might look like this:

class AirTransportationRouter implements Action {

private final Router router;

...

@Override

public void execute(Package packageToBeRouted) {

router.sendViaAirTransportation(packageToBeRouted);

}

}

ConcreteCondition

ConcreteCondition is like ConcreteAction, except that it focused upon conditional features, such as:

- Is High Priority

- Is Local Address

For the most part, they were not Adapters. They were simple enough to reside in the ConcreteCondition implementation itself. Here’s one example:

class IsHighPriority implements Condition {

@Override

public boolean isSatisfied(Package packageToBeRouted) {

return Package.HIGH_PRIORITY == packageToBeRouted.getPriority();

}

}

AndCondition, OrCondition and NotCondition

The AndCondition, OrCondition, and NotCondition trio are the Specification design pattern. They provided the structural framework to assemble the core domain ConcreteCondition objects into any Boolean expression desired.

ActionList

ActionList is the Composite design pattern. Some of our Rules contained multiple Actions to be executed, and ActionList became a way to organize them without tightly coupling them.

The implementation would basically be:

Class ActionList implements Action {

private final List<Action> actions;

...

@Override

public void execute(Package packageToBeRouted) {

for (Action action : actions) {

action.execute(packageToBeRouted);

}

}

}

ConditionAction

We have not seen a previous pattern that would describe ConditionAction. It was one of my favorite classes in the design. It manages the IF that was part of every Rule. Its implementation was something like the following:

class ConditionAction implements Action {

private final Condition condition;

private final Action thenAction;

private final Action elseAction;

...

@Override

public void execute(Package packageToBeRouted) {

if (condition.isSatisfied(packageToBeRouted)) {

thenAction.execute(packageToBeRouted);

} else if (elseAction != null) {

elseAction.execute(packageToBeRouted);

}

}

}

The Problem

I started implementing the design mostly as a proof-of-concept task. This was before I knew Test-Driven Design (TDD) techniques or Dependency Injection. I was able to test my code, but the tests were a bit clunky.

The design was solid. Much like the Rational Expression Evaluator Implementation, the classes and methods fell into place and worked.

But I was also sensing a problem. My tests were a type of Configurer. While I didn’t understand TDD, I had an innate sense that the actual implementation was going to mirror my tests, and it wasn’t pretty. It was going to look like the HORRIBLE code that appeared in One Final Test.

My tests indicated that the design worked, but at the cost of losing intent and comprehension. It was like reading the recipe for a dish without knowing its name, without a photo, or even without knowing the cuisine. You might be able to follow the steps of the recipe, but you still might not have any idea what you were making until you were done.

The Solution

I was a bit distraught. This was not going to work. Intent with Configurer is not much of a concern when only a few objects are created and assembled. But our Routing Rules structure was going to be many objects, and the loss of intent and comprehension was going to be too extreme.

I don’t remember when I had the Aha! moment when I realized I could describe the object organization via a script. From there, it was not too much of a leap to a DSL. I was moving in reverse from what I have been writing all along in this Interpreter blog series. I had started with a design and worked my way back to a DSL.

I wanted just enough of a DSL that would allow us to glue together the functional behaviors in different combinations. Our DSL was going to look more like a script or a program and less like a Specification or REPL.

I realized that the ConditionAction could be an if/then/else statement, which wasn’t much of a conceptual leap. The ActionList could be a block of statements. The ConcreteAction and ConcreteCondition could be like keywords in a traditional programming language.

I had a feeling that we’d be defining Action and Condition named constructs in our script so that we could reference them in other places in the script. They would be like a Macro.

Given these ideas I had a few sketches of what the DSL script might look like:

condition isLocal = IsWithinRadius(10 miles)

action highPriorityRouting = {

if (isLocal()) {

RouteGroundTransportation(Local, Immediate)

} else {

RouteAirTransportation()

}

}

action lowPriorityRouting = {

if (isLocal()) {

RouteLocalGroundTransportation(Local, WhenFilled)

} else {

RouteGroundTransportation(LongHaul)

}

}

action main = {

if (isHighPriority) {

highPriorityRouting

} else {

lowPriorityRouting

}

A few highlights:

- The DSL was imperative. If I had stayed with the original structure of the slide deck rules, then the DSL may have been declarative.

mainwould be the firstactionexecuted, much likemain()in Java or C++.mainreferences namedconditions andactions:isHighPriority,highPriorityRoutingandlowPriorityRouting. Unlike most modern languages where definitions can be referenced before being defined, in this DSL, they must be declared and defined before being referenced. Therefore,mainwas always at the bottom of the script. I could have enhanced the DSL to allow declaration/definition and references to be independent, but it wasn’t worth the effort.- The concrete condition and action names were handles to their class names in the implementation language. I added parentheses in the DSL so that each object could be initialized as needed within the context of the script. The content between the parentheses would be passed as a

String. Each class had its own mini-parser to interpret theStringand configure the class object as needed. MostStrings were simple so parsing was trivial. Packagedoes not appear in the script and yet it is the focal point of the DSL.Packageis injected as the Context inexecute(Package packageToBeRouted)andisSatisfied(Package packageToBeRouted). We can assume that it’s always provided when anActionis executed or aConditionis evaluated. It’s the same as audio Tracks in the Specification Smart Playlist example as well as the variable state storage Context in the Rational Expression Evaluator example. In all three Context is implicit.- The curly braces are optional in the example above. Curly braces are only required for

ActionLists, but they can be useful for readability. NOTE: even if only added for readability, they will still be constructed as anActionListcontaining only oneActionin the composite object parse tree.

The Grammar

Given the example above, I defined a Grammar for the DSL:

SCRIPT ::= STATEMENT [STATEMENT]*

STATEMENT ::= CONDITION_DEFINITION | ACTION_DEFINITION

CONDITION_DEFINITION ::= condition ID = CONDITION

ACTION_DEFINITION ::= action ID = ACTION

ID ::= alphanumeric

CONDITION ::= conditionId | ID | AND_CONDITION | OR_CONDITION | NOT_CONDITION

conditionId ::= concrete condition class name

AND_CONDITION ::= and ( CONDITION [, CONDITION]* )

OR_CONDITION ::= or ( CONDITION [, CONDITION]* )

NOT_CONDITION ::= not ( CONDITION )

ACTION ::= actionId | ID | CONDITION_ACTION | ACTION_LIST

actionId::= concrete action class name

CONDITION_ACTION ::= if ( CONDITION ) ACTION [else ACTION]

ACTION_LIST ::= { ACTION [; ACTION]* }

Keywords and Symbols

conditionactionandornotifelse=(and){and},;- Semicolon is only needed in action lists. It’s anactionseparator, not a line terminator. That distinction would cause a lot of confusion.

Pseudo Keywords

The script contains pseudo keyword references, such as RouteAirTransportation(). These are not keywords defined in the Grammar. They are ConcreteAction classes for which an object will be created and added to the parse tree by the parser. The same applies to ConcreteCondition classes as well. I would need a way to manage this.

Defined Actions and Conditions

The script contains declared references, such as isLocal and highPriorityRouting. They are not keywords or pseudo keywords. They are identifiers declared, defined and referenced in the script. I would need a way to manage them too.

Decomposition Packages

I’ve only listed Package as our Context, but we needed to support different types of Packages. Some Packages were collections of other Packages. For example, a MailBag could contain many Letters each of which requiring their own routing.

Sometimes the components of the decomposed Packages were decomposable themselves.

I would need a way to manage them too and ideally the same technique should work regardless of the layers of Package decomposition.

The Parser

It only took me one day to implement the first workable versions of the Scanner and Parser. My implementation progress was similar to what I described in Rational Expression Evaluator Scanner and Parser Implementation, and progress proceeded about as smoothly. The main difference was that I didn’t know about TDD techniques at the time, so I didn’t have a great set of unit tests, and what tests I had were written after I had coded the feature.

My Scanner supported comments and when parsing hit an unexpected token, it would print the line with line and column numbers for the first character in the token.

The Design

The design I had sketched on the whiteboard was close, but it needed a few elements for the Parser, specifically how to resolve the Pseudo Keywords, Action/Command identifiers, and Decomposed Packages concerns listed above.

I added the following to the design:

- Prototype creates new objects by instructing another object to create a copy of itself.

- Singleton ensures that only one object is created for a class type.

- Decorator layers additional behaviors upon core features.

Enhancements

Here is the enhanced design:

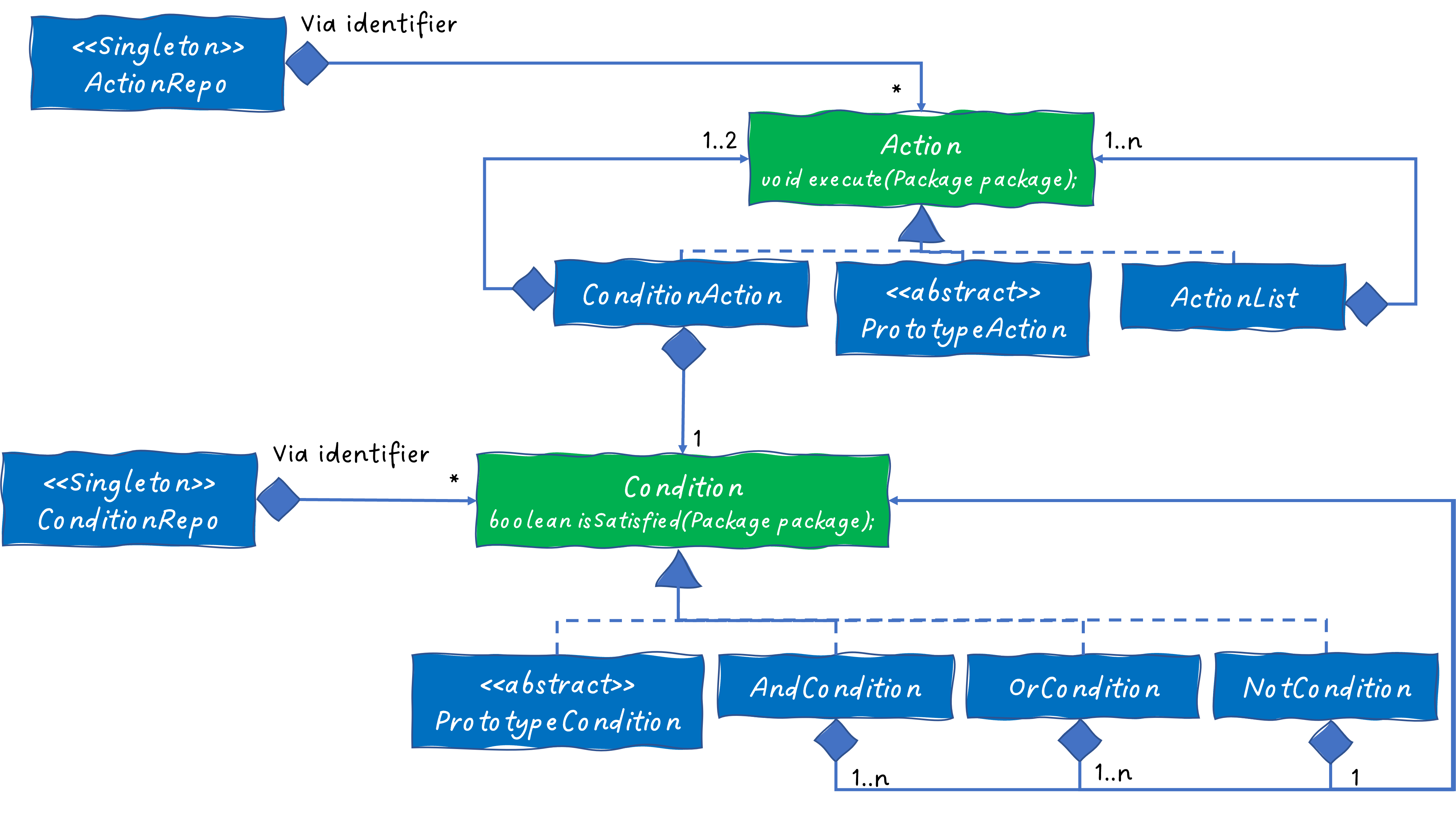

There are only a few differences between this version and the whiteboard version:

ConcreteActionhas been replaced with an abstractPrototypeActionConcreteConditionhas been replaced with an abstractPrototypeConditionActionRepohas been added as a Singleton repository ofActionsConditionRepohas been added as a Singleton repository ofConditions

There is more to the design than could fit in one diagram. I have two additional diagrams which will expand upon PrototypeAction and PrototypeCondition.

When a class diagram gets too large and must be split, I find that interfaces or abstract classes are good connecting points between diagrams. In the diagram above we see how these Prototype classes fit into the overall design. In the subsequent diagrams details related to the Prototype design.

The Singleton Repo classes are collections of Actions and Conditions with an identifier as the key. They will be added to the respective collections during the parsing of these grammar rules:

CONDITION_DEFINITION ::= condition ID = CONDITION

ACTION_DEFINITION ::= action ID = ACTION

action and condition are keywords that indicate to the parser that the ACTION and CONDITION that’s parsed and returned will be known by the ID.

Likewise, when an ID is referenced, the corresponding Action or Condition will be retrieved from the appropriate repo collection.

The Singleton Design Pattern will ensure that there’s only one instance of the Repo collection.

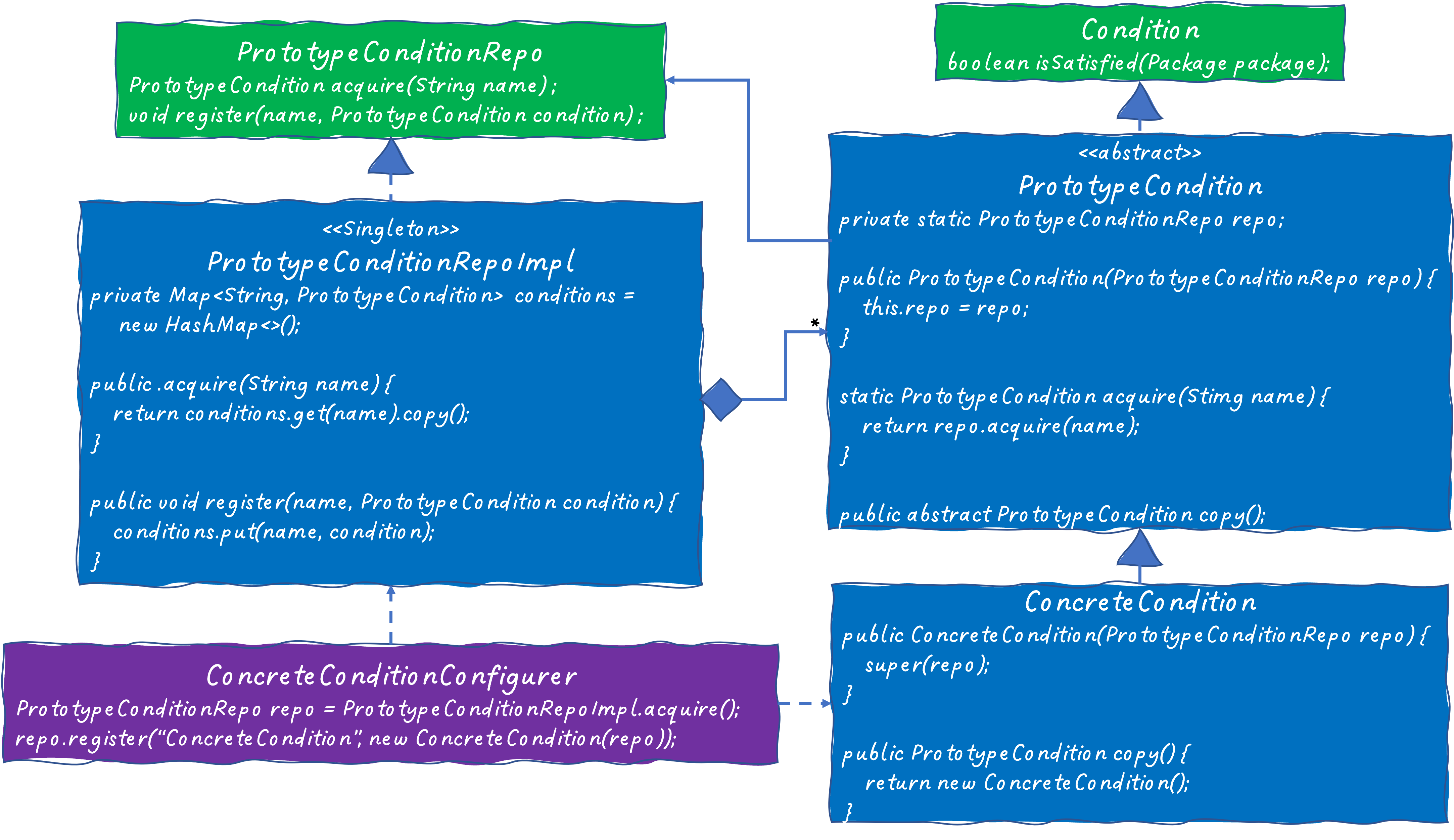

PrototypeCondition

I’m going to start with PrototypeCondition since it’s less complex than PrototypeAction.

The Prototype Design Pattern is not a proof-of-concept implementation. This name is unfortunate, since I think, it can lead to confusion. I feel that Clone or Breeder may have been a better name for the design pattern.

The Prototype Design Pattern is a Creational Design Pattern, but it’s unlike the other Creational Design Patterns. In most creational patterns, the pattern’s implementation knows the class type, which it uses to create an object without the client code knowing the class type or having direct access to the constructor. Prototype does not know the class type or have direct access to the constructor either.

Prototype creates and returns a new object without class knowledge, because it does not create the object via a class constructor. It creates the object by asking an object of that class to make a copy of itself. Constructors are still used, but they are encapsulated in the copy method and unknown to the Prototype implementation. See: Prototype Design Pattern.

The GoF use the method name clone(), but since clone has additional baggage in Java, I’ll use copy() in my diagrams.

I’m using Prototype to manage the Pseudo Keywords, which represent concrete classes in our design. We knew we would have many concrete classes. I didn’t want to update the Parser with class type each time we added a new class, so I used Prototype. Each time we created a new class type for the DSL, an object of that class type was created and registered with the Prototype Repo. The Parser could acquire a new object instance by copying the object stored in the Prototype repo.

Here’s the PrototypeCondition design:

There are two phases with Prototype:

- Registering an object with the Prototype Repo.

- Accessing an object in the Prototype Repo and acquiring a copy from the object.

The following happens at startup:

- The

ConcreteConditionConfigureracquires an instance of thePrototypeConditionalRepoImplwhich is a Singleton that implementsPrototypeConditionalRepo. - The

ConcreteConditionConfigurercreates a new object instance ofConcreteConditionwhile injecting the Repo instance. This is the first place wherenew()is called. We still need to create the object vianew(), but it’s an external call in theConfigurer. TheConcreteConditionis a placeholder example. In practice, there will be many concrete condition classes. An object instance will be created for each. Our implementation language was C++, which supported the ability for the class to create and register an instance of itself during static initialization. Not all programming languages support static initialization. A separate Configurer class may be required as is modeled in the diagram above. NOTE: Since I didn’t understand Dependency Injection, I didn’t use it in our implementation. TheConcreteConditionresolved the Repo Singleton itself. This works, but it results in a circular dependency where the Repo Singleton, and theConcreteConditionknow about and depend upon each other. The enhanced design above removes the circular dependency. - The

ConcreteConditionConfigurerregisters the object instance with thePrototypeConditionRepoSingleton using its class name. NOTE: Any unique key identifier will work, but class name is what we used. PrototypeConditionRepowill contain a mapping of class name to an object of that class. Recall that thePrototypeConditionRepowill have no knowledge of the concrete class. It will only know the object as aPrototypeCondition.

The following happens when the parser acquires a PrototypeCondition object:

- The parser calls

PrototypeCondition PrototypeCondition.acquire(name)which is a static method. PrototypeCondition.acquire(name)acquires thePrototypeConditionfrom the Repo.- The Repo searches for an object in its collection that matches the name. It returns the

copy()of the foundPrototypeConditionobject. - The object’s

copy()method also callsnew(). It’s okay for the object to call a constructor of its own class type.

In short, when the Parser encounters a Pseudo Keyword in the script, it will acquire a PrototypeCondition object from PrototypeCondition via its static acquire(name) method and without the Parser nor PrototypeCondition or the Repo knowing or depending upon the class type.

This independence can be confirmed by following the lines of knowledge and dependency in the design above. The class type and references to new() only appear in the two bottom classes, and they are connected to the design via up-arrows only. No knowledge or dependency flows down to them.

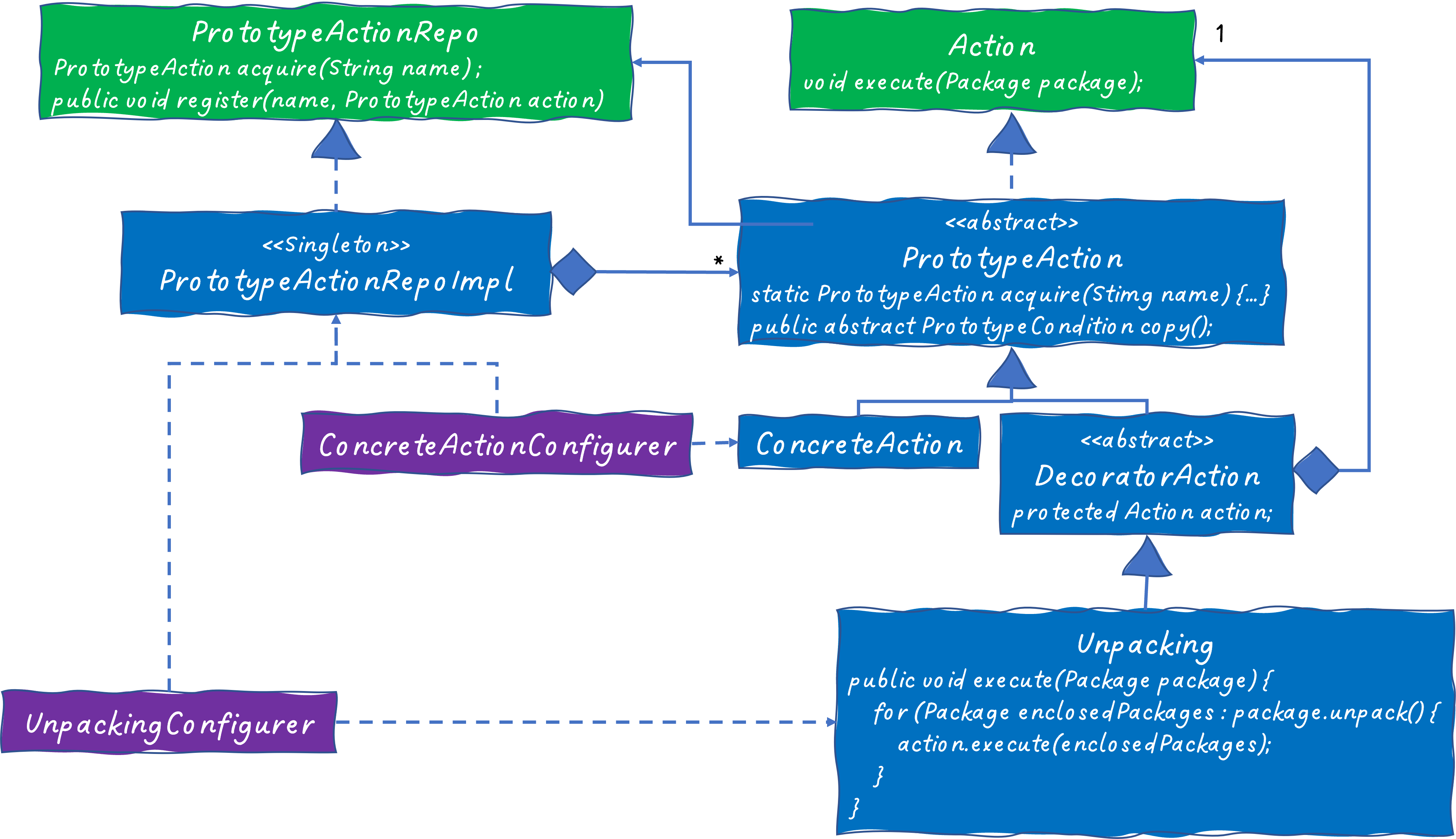

PrototypeAction

PrototypeAction follows the same design as PrototypeCondition. I will include the classes in the PrototypeAction design, but I won’t provide the method details. They are identical, except that Condition would be replaced by Action.

There is a new concept that I’ll review. I have added an abstract DecoratorAction class with Unpacking as a concrete class example. DecoratorAction is based upon the Decorator Design Pattern.

DecoratorAction is a PrototypeAction, which contains an attribute reference back to Action.

Unpacking unpacks the enclosed Packages from the main Package, and it executes its action for each enclosed Package with it as the Context. This looks a lot like the Composite Design Pattern, which is used for ActionList, but it’s slightly different. Composite iterates through its sub-Actions defined in the composite object parse tree executing the original package for each of its sub-Actions. Decorator iterates through sub-Package objects executing its sole action for each of the sub-Packages in the original package.

This allowed us write lines like this in the script:

…

Unpacking {

DoThis();

DoThat()

}

…

Since DecoratorActions contain a reference to Action, and DecoratorAction is a type of Action, we can nest DecoratorActions in the script like these too:

…

Unpacking {

DoThis();

Unpacking {

DoThat()

};

DoOtherThing()

}

…

The Decorator design pattern worked great in the design. It would accommodate any type of Action delegation. In our case, DecoratorActions tended to be looping behaviors. In the examples above, we’re looping through enclosed Packages.

However, DecoratorAction introduced a problem with the Parser. How would the Parser distinguish a DecoratorAction class from a ConcreteClass when it only knew them by their names, which by itself won’t indicate the distinction?

My memory is a bit fuzzy on this, since it was 15 years ago, but here’s what I think I did. After calling PrototypeAction.acquire(name), the Parser asked the returned object whether it was a DecoratorAction or not. This was done via reflection or a method that indicates Decorator status, such as isDecoratorAction(). If it was a DecoratorAction then the Parser would make another descending call into parseAction() and inject to the action into the DecoratorAction object. Otherwise, continue parsing as normal.

The Mystery

After Grammar and Scanner/Parser implementations stabilized, we coded the Routing Rules into a script and started testing it.

Within a few days my QA tester stopped by. We had a lab with several servers that created virtual Packages and moved through our scripted Routing Rules. He was expecting one of the Packages to end up on a specific outgoing loading dock, but it disappeared without a trace. It was like the Package was swallowed within our Routing Rules, and he had no idea what or where to diagnose the unexpected behavior.

He asked whether DSL could support a tracing mechanism. Excellent idea! I added code that documented what each object in the composite object parse tree was doing as it encountered a Package. But each object only documented its behaviors. For example:

ConcreteConditionlogged whether it evaluated to true or false and what data it used to make that decision.AndConditionlogged whether it evaluated to true or false based upon an aggregation of itsConditions.ConcreteActionlogged a summary of what action it performed.ConditionActionlogged whether it executed itsthenActionorelseActionbased upon the Condition value it received.

I figured out a way to indent the logged content indicating scope, for example the then or else Actions behaviors would be indented underneath their ConditionAction log. No individual object was responsible for the entire trace report, but the collective lines produced by each object as it processed a Package documented the entire journey.

We called the trace an itinerary since documented the Package’s journey through the Routing Rules. The itinerary was stored in the Package Context. This was the first time I had to add something to Package that was not part of the original intent. It would not be the last time. We started to refer to this additional content collectively as luggage. In hindsight, I should have created a new class named something like RoutingContext and Package, Itinerary and other luggage elements would have been part of it.

It only took me a few hours to add the itinerary behavior and my QA reran his test. The Package’s itinerary stopped abruptly on the equivalent of an IsExpired rule. This concept doesn’t fit the processing center domain exactly. Recall that our actual domain was message routing, and if certain messages were too old, in some cases 15 minutes, they had expired, and they were dropped like yesterday’s old news.

The itinerary indicated that the Package was 3 hours past its expiration timestamp. My QA scratched his head, and then he checked the clocks on the servers in the lab. The one that created the Package and the one that hosted the scripted Routing Rules were 3 hours out of sync. He fixed the errant clock, tried it again, and the Package was processed through the scripted Routing Rules exactly as we expected. Who knows how long it could have taken to diagnose the clock mismatch without the itinerary.

We leaned upon the itinerary greatly after that. It was trivial for us to confirm that Packages were being routed as we expected. Any unexpected routing was quickly found and addressed.

We expanded upon this idea as the project matured. We created concrete Log, Error and Warn Actions, which we added to our routing rules as needed.

The Regions

Different processing centers would service different geographical regions. The regions were dynamic values discovered at runtime. I originally envisioned the DSL/Grammar/Parser as a compiler. At system start up, our scripted rules were compiled into one large composite object parse tree with main at the top. Each Package was processed through the same main object rooted parse tree, which never changed.

To address runtime region knowledge, I added a Template feature to the DSL/Grammar so that we could inject runtime parameters into the DSL and generate new composite object parse trees at runtime. Its name was inspired by C++ Templates, and it’s the same concept as Generics in Java.

The new Template Rule was added and looked something like this:

STATEMENT ::= CONDITION_DEFINITION | ACTION_DEFINITION | TEMPLATE_DEFINITION

TEMPLATE_DEFINITION ::= ID < ID [, ID] > = { String }

String was any string of characters. It might look like the following in the script:

template RouteLocalTransportation<REGION> = {

if (isRegional) {

RouteLocalGroundTransportation(<REGION>)

}

}

…

Templates were stored in a Template Repo as Actions and Conditions were as well. The Template Repo contained the list of parameterized types and the complete Template definition.

When the Parser encountered an identifier returned from the Scanner, it would determine what type of identifier in the following order:

- Keyword, which was hardcoded in the Parser.

- Template Identifier if it were in the Template Repo.

- PrototypeAction/PrototypeCondition Identifier if it were in the respective Prototype Repos.

- Action/Condition Identifier if it were in the Action/Condition Repos.

Once a Region was known at runtime, our code would reference a Template identifier with the REGION name injected, as such: RouteLocalTransportation<NorthEastRegion>. The Parser would look up RouteLocalTransportation in the Template Repo, which would return the whole String with REGION still in it. The Parser would substitute the parameterized type, NorthEastRegion, for the Template name, REGION, into the Template to create a String like this:

if (isRegional) {

RouteLocalGroundTransportation(NorthEastRegion)

}

It would then parse that String into a small composite object parse tree allowing the system to support the NorthEastRegion at runtime.

This use of the DSL/Grammar/Parser was more akin to an interpreter. The named Template, Action, and Condition object composite trees residing in their respective Repos were more like libraries that the newly interpreted instruction could access.

We decided to try the Template ideas for proof-of-concept implementation in the morning. I had it working before the end of the day. I was surprised by how easily and quickly the design and implementation accommodated it. The only issue was that if the Parser had a Template parsing issue, the line/column information was a bit skewed, so it was a little harder to debug any Template typos.

We later realized that we could simplify our scripted Routing Rules using Templates as well. Template was created for regional support, but it wasn’t limited to regional support.

We were also able to leverage the On-Demand nature of the DSL such that we could construct a String in the DSL/Grammar at runtime and parse it to create a composite object parse tree on-demand. On-Demand parsing was created for Template support, but it wasn’t limited to Template support.

Template was flexible enough to accommodate Templates of Templates.

The Updates

I mentioned previously that I was suspicious that our PowerPoint routing rules were not complete or correct. We found out that was the case during field testing.

There was a major testing effort at a processing center with all related parties. We weren’t the only software shop working on the package processing center project.

Two members of our team were on site for the exercise. Routing wasn’t functioning as expected on site. Once our crew observed what was really needed, they spent a few hours after the day’s exercises were over updating our Routing Rules script. They uploaded the updated script on the package processing center servers on site the next day, and it worked. They were able to fix the problems without having to update or access our source code or our versioning system.

We committed the updated script into our version management system when they returned.

The Party

I was sitting next to our PM at the annual company holiday party. A customer was sitting on his other side. The customer was happy about the updates to the package processing center. I was a bit confused since I knew we had not yet delivered our code yet.

I asked my PM about it, and he said, “You know how Alan and Joe have been working on that subset of the scripting rules? That’s what was delivered. It’s a subset of the Routing Rules for an existing package processing center that’s not using some of the newer features yet.” Our routing DSL script was already in the field, and I had no idea since there had not been any issues with it in the field.

Different routing functionality could be provided for different package processing centers from the same code base. The only difference was in the scripted Routing Rules.

I have one additional story related to Joe. In the original Grammar, the semicolon was an Action separator, not a line terminator. I could usually keep this straight since I had defined it. However, Joe kept trying to terminate almost every line with a semicolon, which I understood, since that’s what our implementation language did. I had to fight the urge to add a semicolon at the end of the last Action myself.

He complained to me several times about it. I was able to fix it in the Parser easily. In the ActionList parsing, I updated the code to accept redundant semicolons and ignore them without generating a parsing error.

The Driver

The customer wanted to extend routing beyond the processing center. Drivers were an extension of routing as well. The customer wanted to port the software to the Android environment.

Our first task was to just get something working on Android. By this time our Routing Rules script had gotten large, and it was dedicated to routing within the processing center. Its Routing Rules were different than what a driver would need.

We created a new script dedicated to Android for the driver without major updates to the implementation. The Android driver-based script used the same DSL/Grammar, but rather than being hundreds of lines long it was only a dozen or so lines long.

We were able to experiment with Driver based Routing Rules for Android relatively easily without the additional baggage of the original Routing Rules.

The Flexibility

When behavior updates were needed, we found that:

- About 95% of the time, we could address them in the script without having to touch any of the source code.

- Of the remaining updates, about 95% of the time, we could address them with a new concrete

ActionorConditionclass. Prototype allowed us to plug them in easily without affecting the rest of the implementation. - Of the remaining updates, it was a concept not supported by the DSL/Grammar or Parser, such as the introduction of

Template. This involved more effort, but the loose coupling of the design accommodated the updates easily.

By the time we were done, the script was about 2,000 lines long, with comments, and the composite object parse tree had about 2,000 objects in it.

The Summary

Our Routing Rules DSL was an experiment. We were surprised by how well it worked. It provided the glue that allowed us to connect the different behaviors of our product without tightly coupling them. It was flexible and when updates were required, they could be made easily.

While we didn’t start with a DSL/Grammar, we ended up there. The original design and implementation were solid enough so it could accommodate the DSL and Grammar concepts.

To the best of my knowledge no implementation bugs were ever discovered beyond our own testing.

The Routing Rules DSL Interpreter was one of the most enjoyable software projects I worked on in my career.

The References

See: Interpreter Design Pattern Introduction/References for overall references.