Abstract Factory Design Pattern Without the Confusion

Building Smart, Swappable Systems One Layer at a Time

Introduction

Abstract Factory may sound, well, abstract—but the problem it solves is anything but. It gives you a way to produce consistent families of objects without tightly coupling your code to specific classes. It’s especially helpful when your application needs to support different configurations or behaviors at runtime.

In this post, I’ll show how Abstract Factory works by building up a real example using a Warrior and multiple weapon systems. We’ll start with interfaces and test doubles, add dependency injection, and end with a clean, layered design that’s easy to extend and reason about.

Gang of Four’s Introduction to Abstract Factory

The Gang of Four (GoF) organized their book in four basic sections:

- The 80 page overview, which presents the foundations for design patterns as well a use case to provide a little context.

- The Creational Design Patterns, which catalogs patterns for creating and assembling objects without directly depending upon class type. They are the topic of this blog series.

- The Structural Design Patterns, which catalogs the structure of objects working together in repeating patterns.

- The Behavioral Design Patterns, which catalogs the behaviors that emerge from objects working together in repeating patterns.

Patterns were presented in alphabetical order within each category. Therefore, Abstract Factory was the first design pattern presented in detail in their book. It’s a daunting first design pattern to encounter if reading the book from cover to cover.

If you’ve ever tried to read the Abstract Factory diagram in GoF and ended up cross-eyed from the overlapping lines—trust me, you’re not alone. Imagine seeing this as your first design pattern.

Builder is the second pattern cataloged in the book, and it’s just about as intimidating. It’s the next pattern in this creational blog series.

The first several times I attempted to read the GoF, I made it through the foundations and the use case, but once I hit Abstract Factory and Builder, I was so flummoxed that I put the book back on the shelf. I describe my struggles with the GoF, and how I got past them in It’s Your Move.

My Introduction to Abstract Factory

Dear Reader, I promise to be gentler than the GoF were with me.

Here is Abstract Factory in a Nutshell:

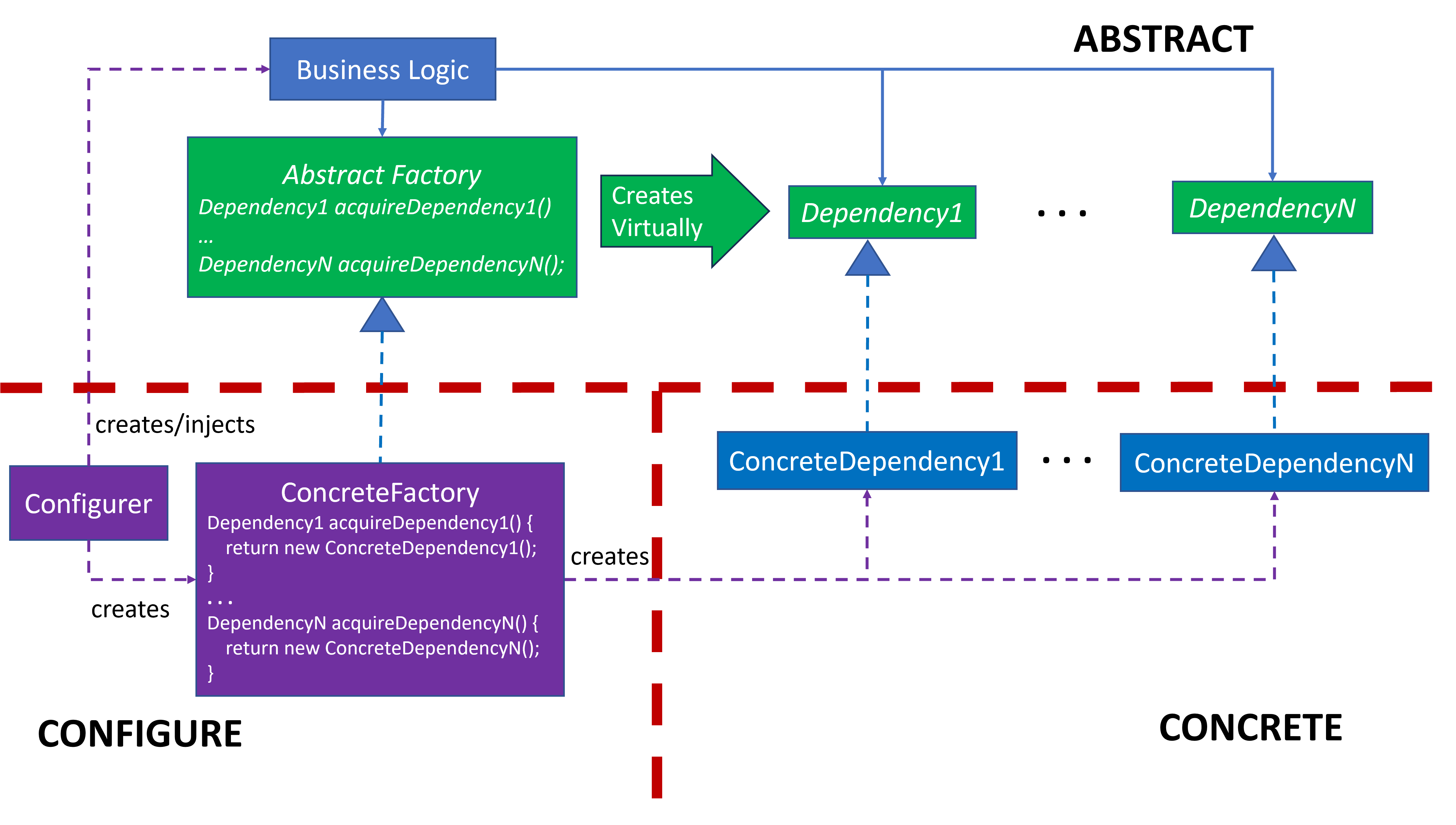

Abstract Factory is the Strategy Design Pattern where the behavior declared in the interface is a Factory method that acquires and returns an instance to an abstract declaration.

Unlike the GoF, Abstract Factory is not the first design pattern I have presented. I’m about halfway through their pattern catalog. I’ve covered Design Pattern Foundations, Essential Design Patterns and Composable Design Patterns. I illustrated how the Essential Design Patterns work together to create the Hexagonal Architecture/Design. Hopefully everyone reading here feels comfortable with design patterns.

I have previously mentioned Abstract Factory as well in the:

- Creational Design Pattern series introduction, with a brief description.

- Abstract Factory section of the Factory Design Patterns blog with another description.

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern section of the What Is Cohesive Abstraction? blog with an example.

The GoF dumped Abstract Factory, whole cloth, in its entirety in their book. I will present Abstract Factory step-by-step layering in its parts with context while building upon the content that I presented previously.

Abstract Factory Intent

It took a long time before I understood the intent of Abstract Factory. I knew that Abstract Factory helps ensure that all dependencies for an application are consistent for a specific environment or scenario. But its importance still didn’t resonate with me.

In A Cautionary Tale, I described work situation where an integration test was connected to our production database. When the test cleaned up upon completion, it deleted a table in our production database losing customer data. Had we configured our system with an Abstract Factory, it would have been much more difficult to have configured our test environment with a production dependency.

While thinking about this blog, I realized that I was missing another Abstract Factory scenario—creating multiple instances. In most Creational Design Patterns, the caller indirectly depends upon the concrete class type of the object being created even if the class type is encapsulated and unknown to the caller. I described this situation in the beginning of the Dependency Injection (DI) blog how this makes unit testing difficult. DI helps resolve this indirect dependency issue by creating the instance outside the boundary of the application and injecting it into the application.

Traditional DI injects one instance of a class type into the application before the application executes any behavior. This suffices for dependencies that require only a single instance, such as Adapters to databases or messaging systems, but it doesn’t work well when the application needs to create an instance or multiple instances of a class type as part of its behavior while it executes.

Abstract Factory will address both scenarios:

- Consistent Dependencies

- Multiple Object Instances

There may be other scenarios where it will be useful, but I won’t present them.

Abstract Factory Use Case

I will return to the Call of Duty example introduced in What Is Cohesive Abstraction? with a few modifications as the use case example to explain Abstract Factory.

This use case will feature a Warrior who uses a Launcher/Projectile Launcher System, such as a Rifle/Bullet, Bazooka/Bazooka Shell or Bow/Arrow. The Warrior’s behavior consists of:

- Acquiring a Launcher.

- Acquiring a set of Projectiles and loading those Projectiles into the Launcher up to the Launcher’s Projectile capacity.

- Aiming and launching each of the Projectiles loaded into the Launcher.

In more concrete terms, if the Warrior were a Rifleman, then the Rifleman would load six bullets into the rifle, take aim and fire the six rounds.

This use case will address both Abstract Factory scenarios listed above, since it will ensure that the Launcher and Projectile dependencies are consistent, and the Warrior can acquire as many Projectile instances as needed.

I will construct the Warrior design in phases using the Abstract Factory within a test environment to confirm the Warrior’s behavior. Then I’ll show how the design can accommodate Rifle/Bullet, Bazooka/BazookaShell and Bow/Arrow.

Abstract Factory is Comprised of other Design Patterns

Abstract Factory is comprised of one Design Pattern Principle and several Essential Design Patterns:

Program to an interface, not an implementation

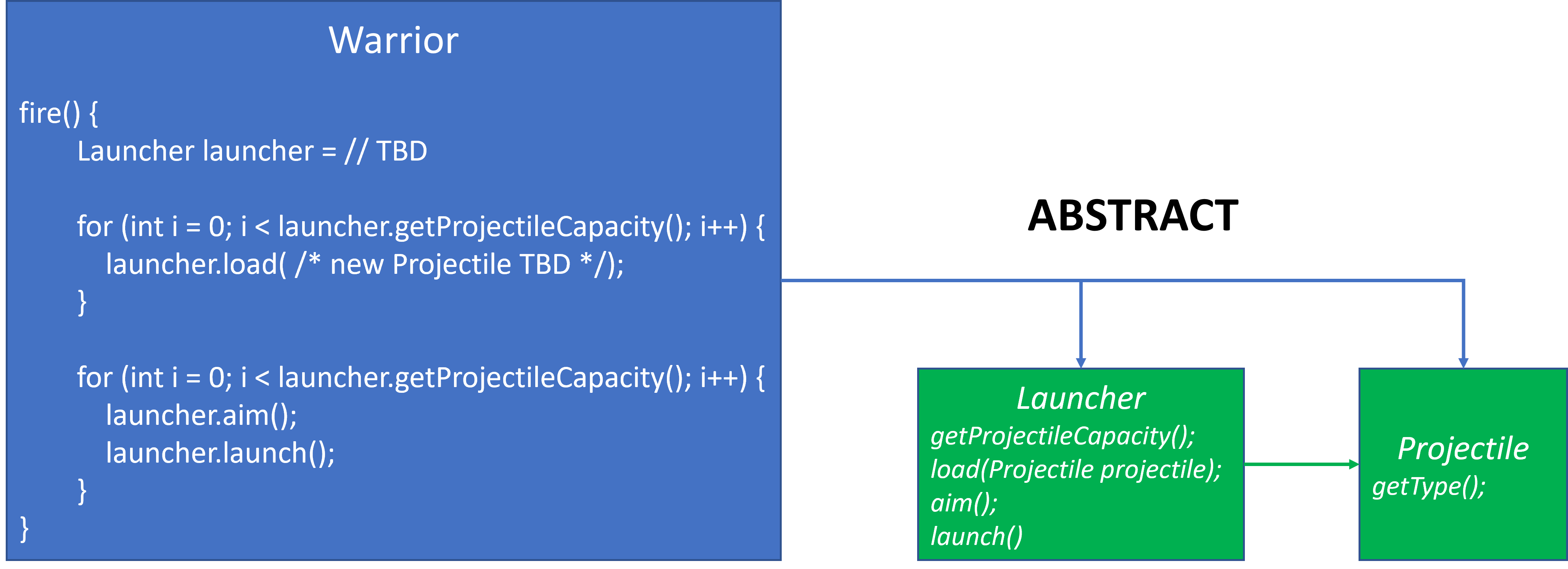

This principle applies to almost every design pattern, but it’s even more so with Abstract Factory. The Warrior has two interface dependencies: Launcher and Projectile.

Launcher and Projectile need to be consistent. For example, we can’t attempt to load an Arrow into a Rifle. We also need the ability to instantiate any number of new Projectile instances.

The Abstract Factory will resolve these dependencies, so that they are consistent pairs and allow for multiple instances.

Strategy

Launcher and Projectile are Strategies, since each will be realized via different sets of concrete classes, such as: Rifle/Bullet, Bazooka/BazookaShell and Bow/Arrow.

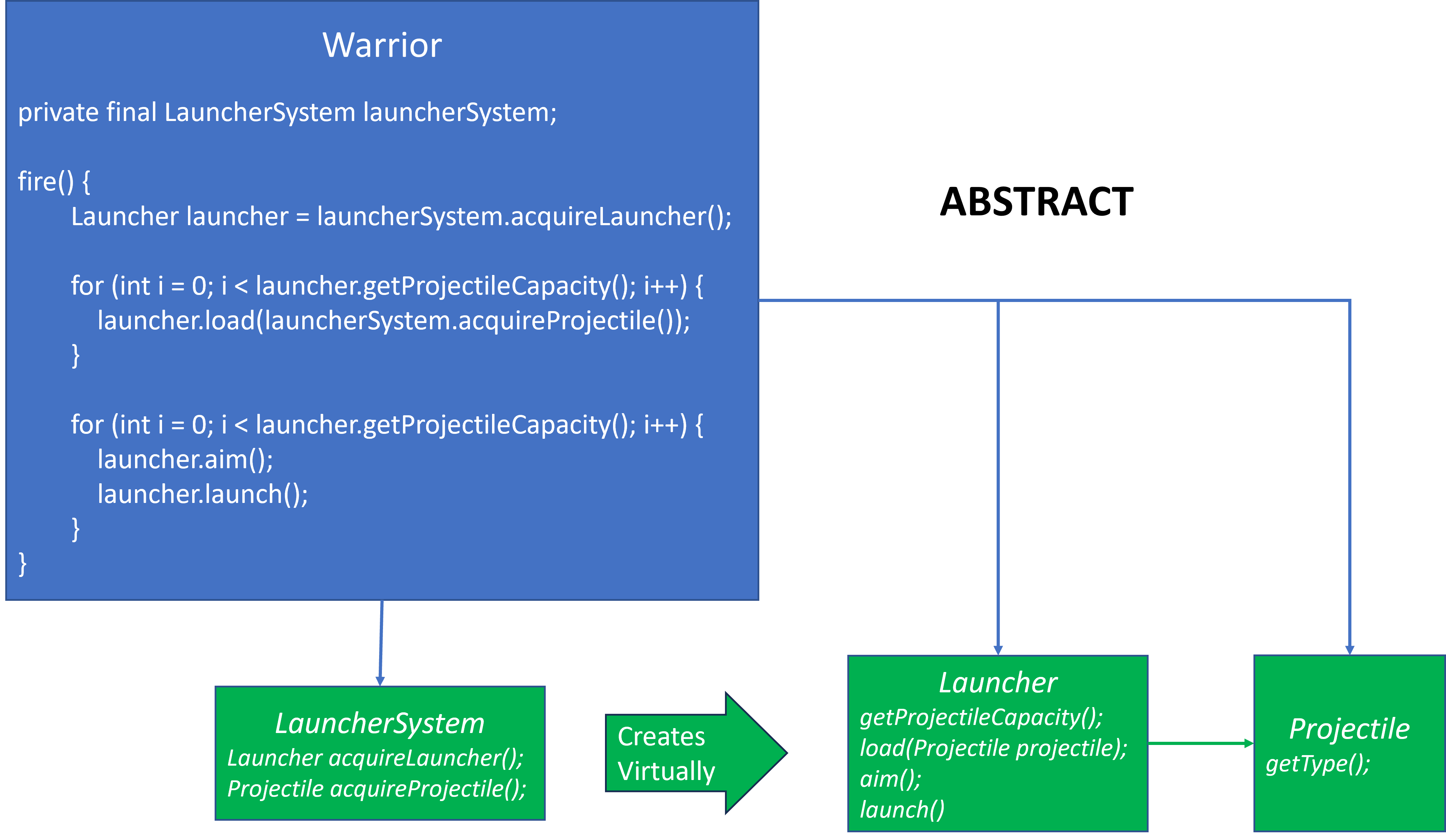

However, the important Strategy component of the pattern is the LauncherSystem Abstract Factory interface. LauncherSystem is a Strategy whose responsibility is to acquire dependencies associated with the design. It’s an abstraction and a factory, hence the pattern name: Abstract Factory. Once the LauncherSystem reference is resolved, which I haven’t shown yet, the Warrior can acquire a Launcher and Projectiles.

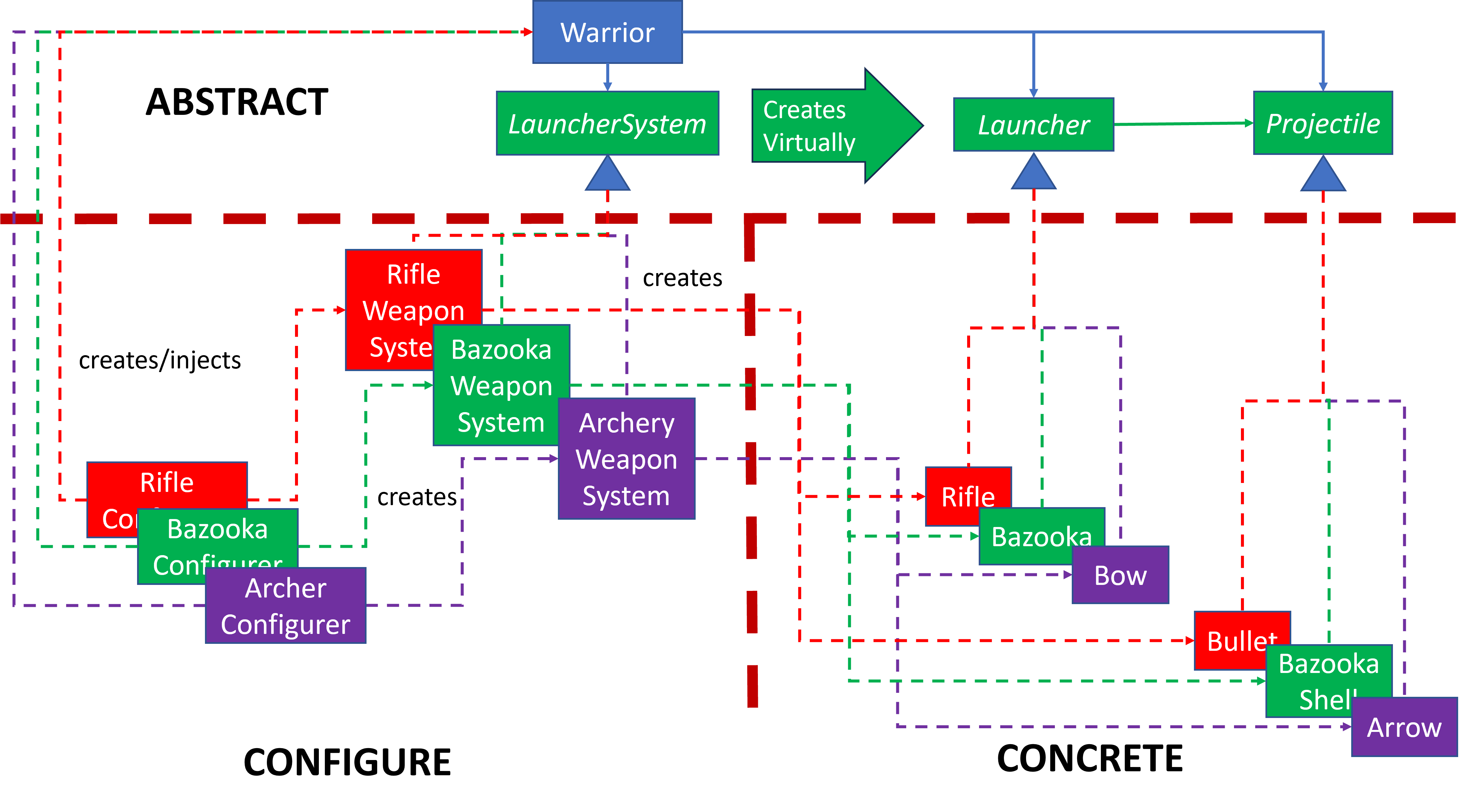

When added to the design, we get:

Factory

LauncherSystem is an abstract Strategy that declares the ability to acquire Launcher and Projectile virtually. Concrete instances of LauncherSystem realize that potential using a Factory.

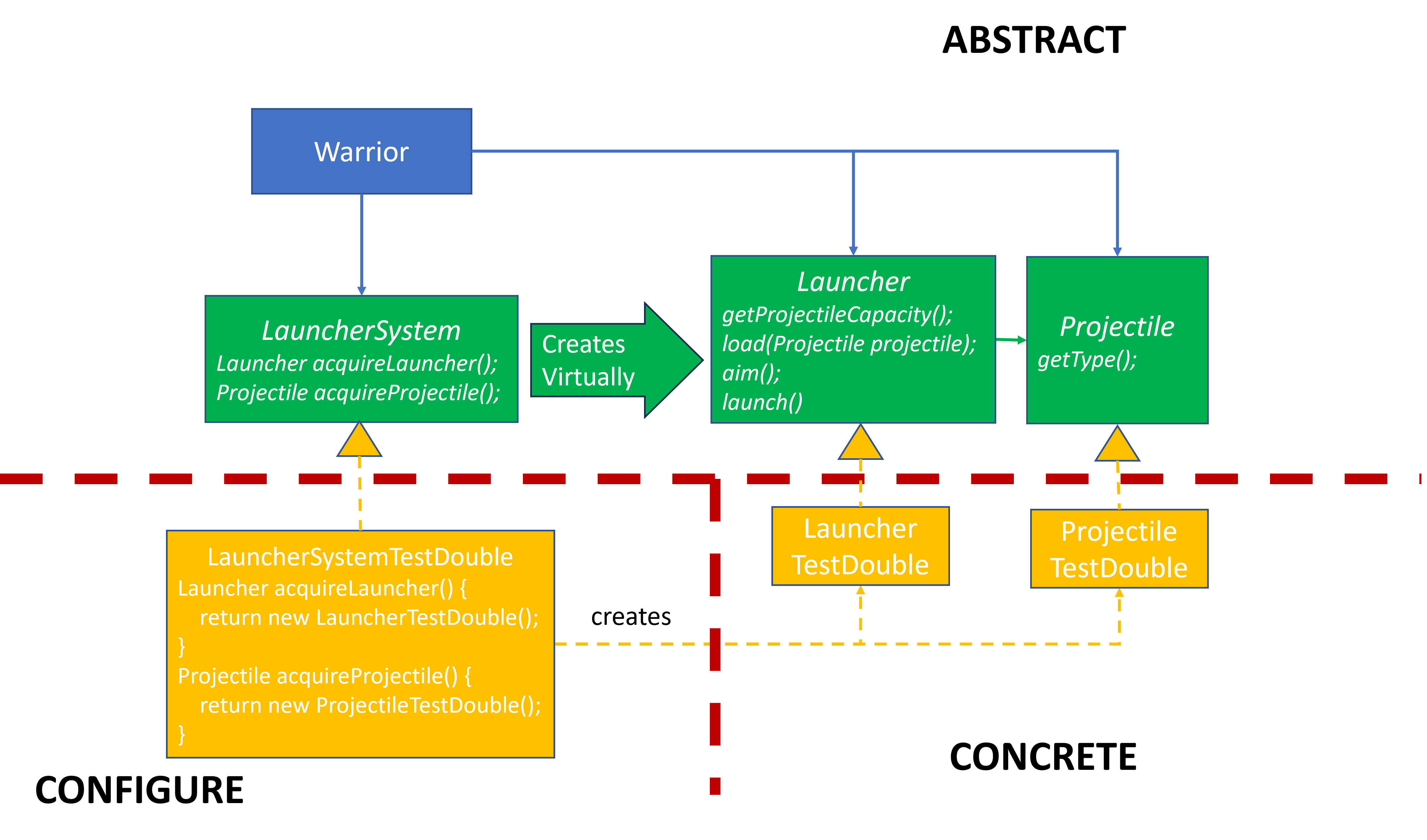

Here’s the design with a LauncherSystemTestDouble, which creates LauncherTestDouble and ProjectileTestDouble. I have removed the fire() code from Warrior for space considerations. Its presence is implied.

The dashed red line represents architecture boundaries especially to highlight the flow of dependency and knowledge, which always crosses these boundaries in one direction. Dependency and knowledge flow upward toward abstraction, as represented by all arrows crossing the horizontal line pointing upward. Dependency and knowledge flow to the right from configuration to concrete as represented by all arrows crossing the vertical line point toward the right.

This is the entire Abstract Factory design. Abstract Factory is a specific application of the Strategy design pattern where the behavior is acquiring object instances.

Dependency consistency resides in the concrete Factories, but the pattern can’t guarantee or enforce it. A developer could easily define a LauncherSystem where the Launcher is a Rifle and the Projectile is an Arrow. However, the pattern can encourage and facilitate dependency consistency. The LauncherSystem is not complex. The code snippet in the diagram is almost the entire implementation. Visual inspection should help ensure that the acquired Launcher and Projectile are consistent. It would not be difficult to design unit tests that confirm this as well.

If each LauncherSystem enforces dependency consistency, the rest of the design should not need to be concerned about it.

Dependency Injection and Configurer

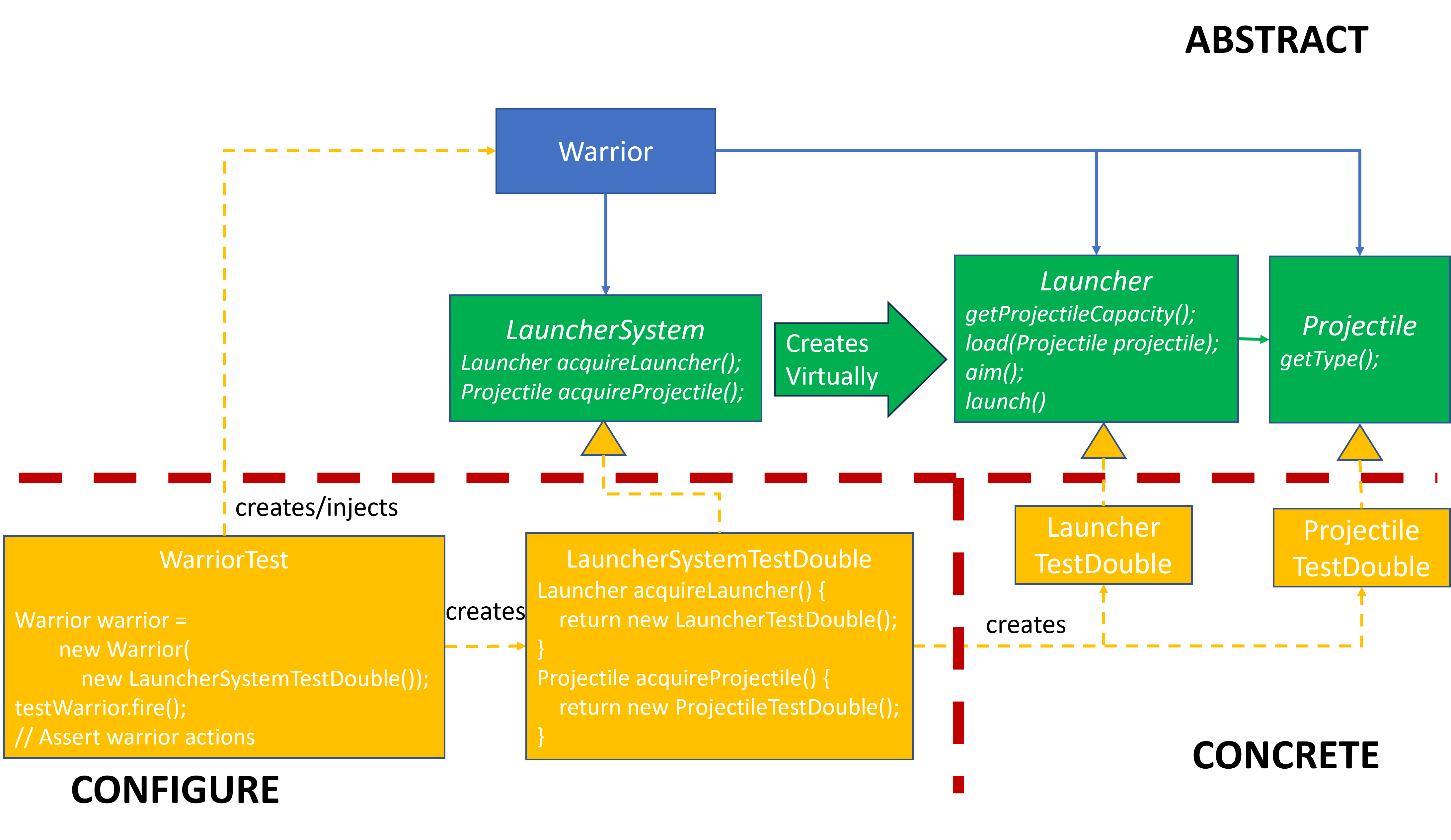

At this point, the GoF are done with the design, but I’m not. We still don’t know how Warrior resolves the LauncherSystem reference. There may be several ways to resolve this, but I prefer Dependency Injection with a Configurer. WarriorTest is a test, but it’s also a Configurer. It creates an instance of LauncherSystemTestDouble and injects it into Warrior.

Here is my complete Dependency Injected Configurer design:

Testing the Use Case

Here is an example of Java code for the above:

//////////// ABSTRACT ///////////

interface LauncherSystem {

Launcher acquireLauncher();

Projectile acquireProjectile();

}

interface Launcher {

int getProjectileCapacity();

void load(Projectile projectile);

void aim();

void launch();

}

interface Projectile {

String getType();

}

class Warrior {

private final LauncherSystem launcherSystem;

public Warrior(LauncherSystem launcherSystem) {

this.launcherSystem = launcherSystem;

}

public void fire() {

Launcher launcher = launcherSystem.acquireLauncher();

for (int i = 0; i < launcher.getProjectileCapacity(); i++) {

launcher.load(launcherSystem.acquireProjectile());

}

for (int i = 0; i < launcher.getProjectileCapacity(); i++) {

launcher.aim();

launcher.launch();

}

}

}

//////////// CONCRETE ///////////

class LauncherTestDouble implements Launcher {

private List<String> actions;

private Projectile projectile;

public LauncherTestDouble(List<String> actions) {

this.actions = actions;

}

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 2;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

actions.add(String.format("Load: %s", projectile.getType()));

}

@Override

public void aim() {

actions.add("Aim LauncherTestDouble");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

actions.add(String.format("Launch %s", projectile.getType()));

}

}

class ProjectileTestDouble implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "ProjectileTestDouble";

}

}

//////////// CONFIGURE ///////////

class LauncherSystemTestDouble implements LauncherSystem {

private List<String> actions;

public LauncherSystemTestDouble(List<String> actions) {

this.actions = actions;

}

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new LauncherTestDouble(actions);

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new ProjectileTestDouble();

}

}

private static void testWarrior() throws Exception {

// Given

List<String> actions = new LinkedList<>();

LauncherSystem launcherSystem = new LauncherSystemTestDouble(actions);

Warrior warrior = new Warrior(launcherSystem);

// When

warrior.fire();

// Then

assertEquals("[Load: ProjectileTestDouble, Load: ProjectileTestDouble, Aim LauncherTestDouble, Launch ProjectileTestDouble, Aim LauncherTestDouble, Launch ProjectileTestDouble]", actions.toString());

}

Additional Use Case Launcher Systems

Most of the work for this design is in defining the interfaces, providing the test doubles and testing the Warrior. Adding more LauncherSystems is trivial once the foundations have been laid.

Since this pattern is about creating LauncherSystems, the additional concrete class implementations only contain print statements that describe what they would do rather than provide an actual implementation. In an actual application, each of these methods would have more sophisticated implementations with accompanying automated tests. Print statements keep the example small, while still conveying different text-specified behaviors for each LauncherSystem.

Nothing in the design or implementation changes above the horizontal dashed red line. The Abstract portion of the design does not depend upon nor know about the concrete elements below it.

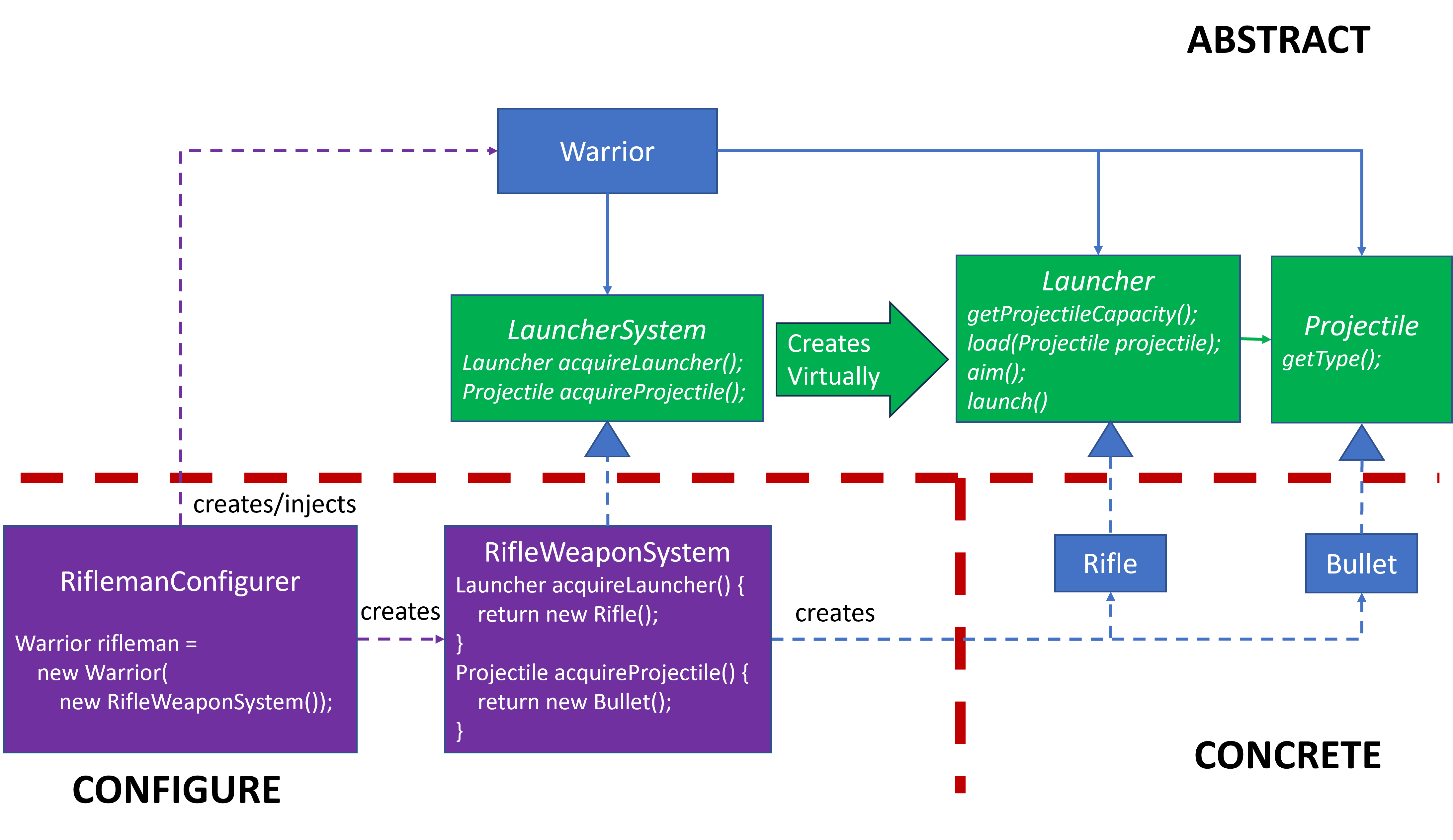

Rifle/Bullet

//////////// CONFIGURE ///////////

class RifleWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Rifle();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new Bullet();

}

}

//////////// CONCRETE ///////////

class Rifle implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 6;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Load %s into rifle\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.println("Aim down rifle barrel");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class Bullet implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "Bullet";

}

}

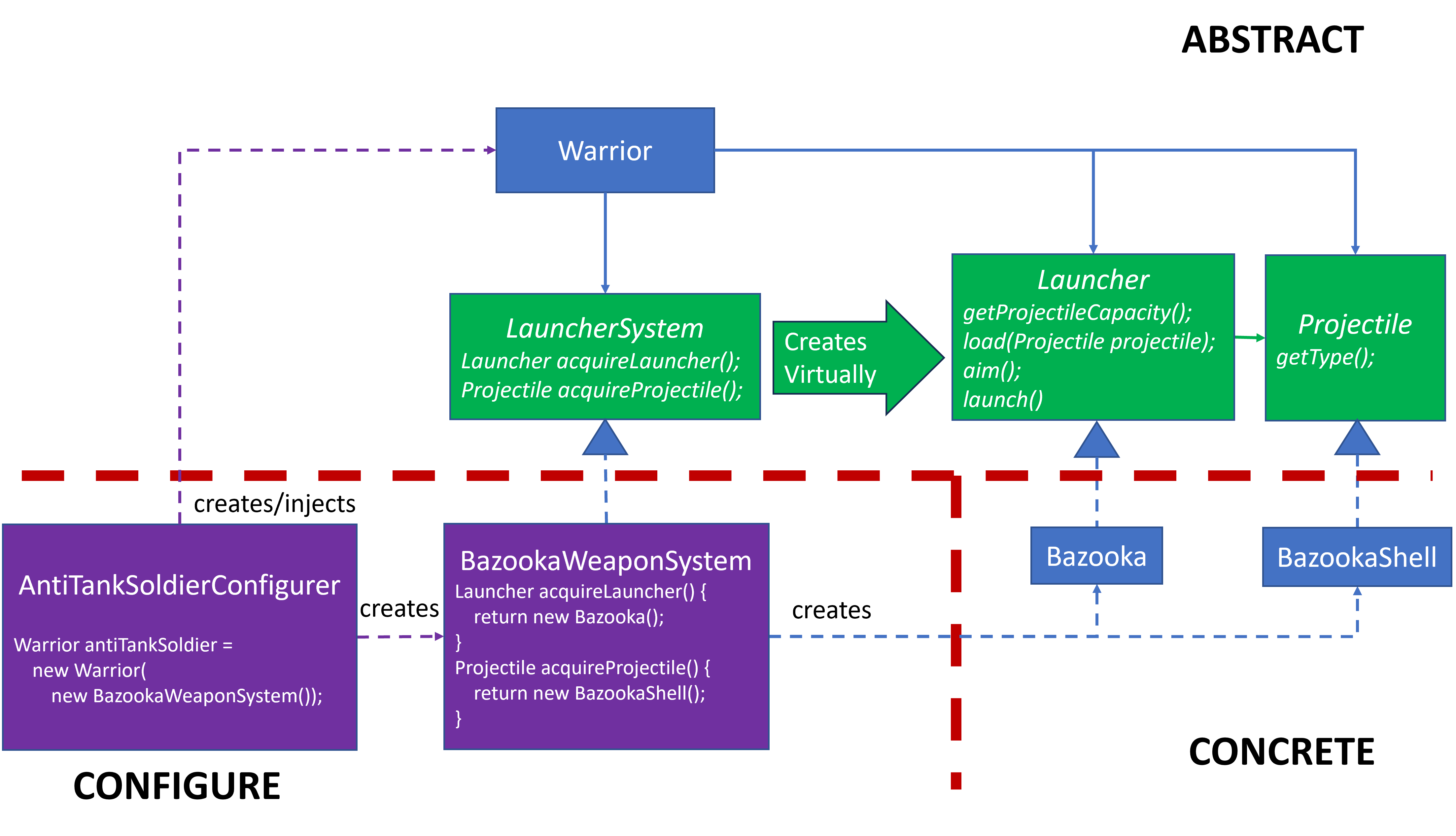

Bazooka/BazookaShell

//////////// CONFIGURE ///////////

class BazookaWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Bazooka();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new BazookaShell();

}

}

//////////// CONCRETE ///////////

class Bazooka implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 1;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Load %s into bazooka\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.println("Aim down bazooka site");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Squeeze bazooka trigger to launch %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class BazookaShell implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "BazookaShell";

}

}

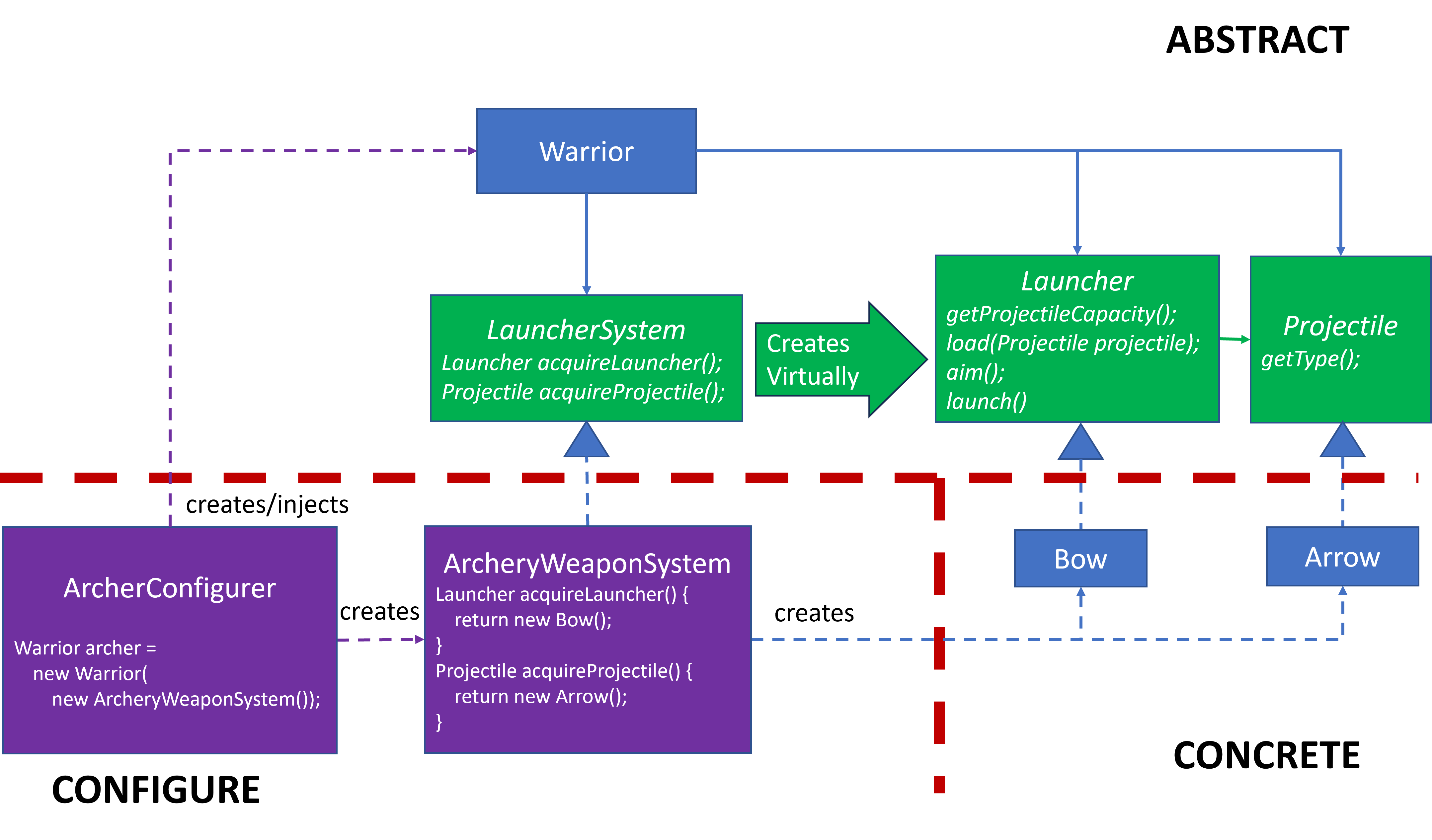

Bow/Arrow

//////////// CONFIGURE ///////////

class ArcheryWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Bow();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new Arrow();

}

}

//////////// CONCRETE ///////////

class Bow implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 1;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Notch %s into the bow string\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.format("Pull back bow string and aim down %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Release bow string to launch %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class Arrow implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "Arrow";

}

}

The Dirty Main

Here’s main(), which executes the entire set of code above. While my class diagrams include Configurers, the implementation doesn’t include specific Configurer classes. Configuration happens in main(). It instantiates several Warrior instances and has them fire.

public class AbstractFactory {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Test.test();

System.out.println();

Warrior rifleman = new Warrior(new RifleWeaponSystem());

rifleman.fire();

System.out.println();

Warrior antiTankSoldier = new Warrior(new BazookaWeaponSystem());

antiTankSoldier.fire();

System.out.println();

Warrior archer = new Warrior(new ArcheryWeaponSystem());

archer.fire();

}

}

When this code is executed, it produces the following output, which shows how the same Warrior implementation produces different results depending upon the concrete LauncherSystem that’s been injected into it:

End Tests

Load Bullet into rifle

Load Bullet into rifle

Load Bullet into rifle

Load Bullet into rifle

Load Bullet into rifle

Load Bullet into rifle

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Aim down rifle barrel

Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot Bullet

Load BazookaShell into bazooka

Aim down bazooka site

Squeeze bazooka trigger to launch BazookaShell

Notch Arrow into the bow string

Pull back bow string and aim down Arrow

Release bow string to launch Arrow

Bob Martin describes configuration as the lowest and dirtiest portion of the design. It may reside in main() as I’ve shown above, where it resides in the dirtiest part of the program as Martin has called it.

I won’t say that main() is dirty, but I’ve found that it’s often where dynamic configuration resides.

The GoF Abstract Factory Mess

I feel that a messy diagram will lead to a messy design and messy implementation. The GoF’s Abstract Factory class diagrams are messy in my opinion. It’s possibly the messiest design in their catalog. There are many similar named elements, and the class diagram cannot be drawn without lines crossing each other. Abstract Factory may be their only design pattern diagram with crossing lines.

Any Abstract Factory class diagram that includes at least two concrete factories and two dependencies will have lines crossing each other, because the 2+ Factory/2+ Dependency Abstract Factory has a complete 3-to-3 bipartite graph, which I know cannot be planar due to Kuratowski’s Theorem thanks to Professor Johnson, my graph theory professor in college.

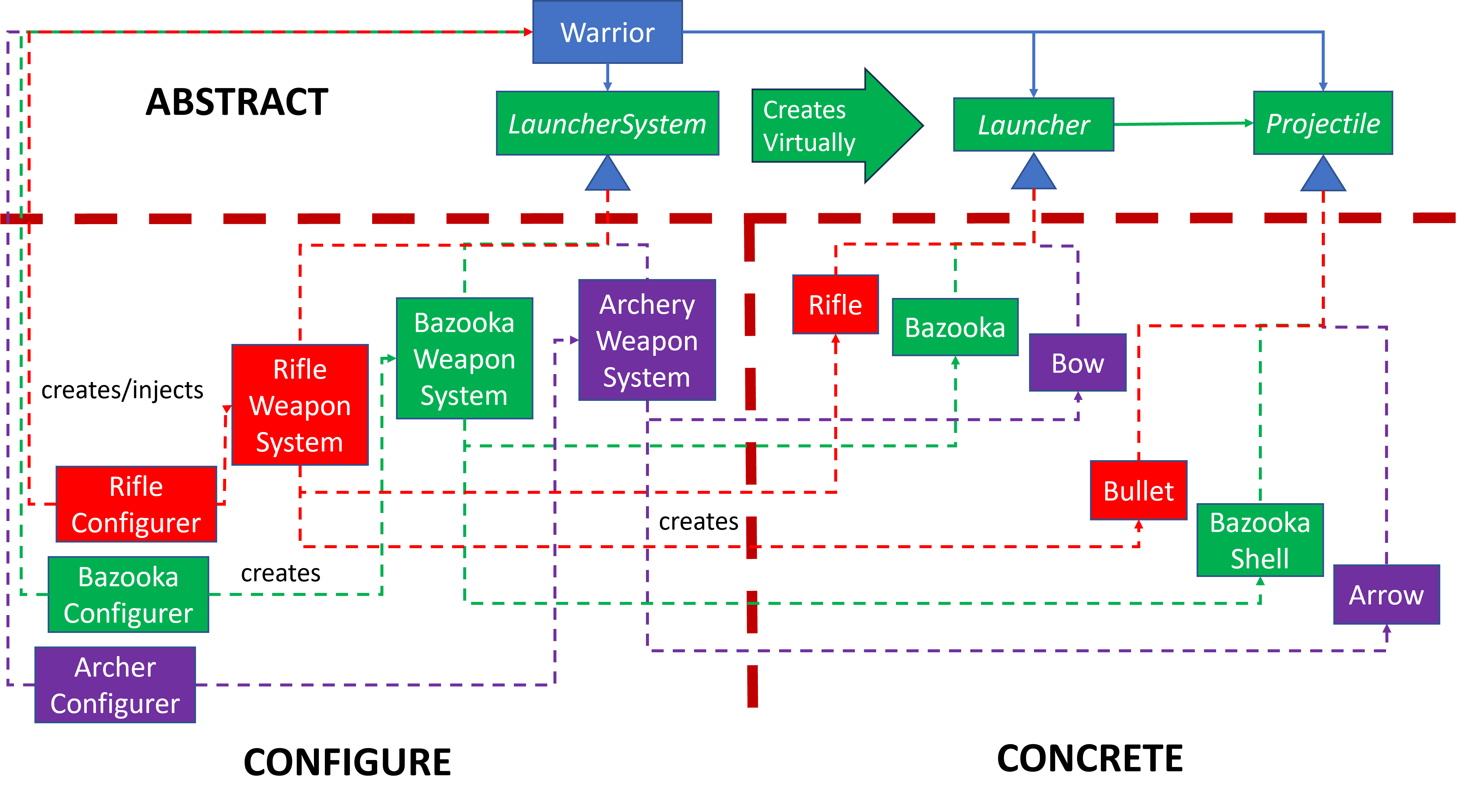

My previous diagrams have been planar, since I limited them to one concrete Factory. Here’s my complete design with all three LauncherSystems added:

My complete diagram has so many crossing lines that it reminds me Broadway Boogie Woogie by Piet Mondrian

I color coded this diagram differently. Usually I use green for interfaces, blue for implementation, purple for configuration and red for externals. That’s still the case in the Abstract section, but the colors below the red dashed horizontal line take on a different one time meaning so that it’s a little easier to keep track of the relationships between cohesive classes, especially in the many crossing lines:

- Red is for the Rifle/Bullet classes.

- Green is for Bazooka/BazookaShell classes.

- Purple is for Bow/Arrows classes.

There’s another way to imagine this. Don’t imagine this class diagram on one plane. Imagine it on multiple stacked planes. The Red, Green and Purple planes are stacked on top of each other where they each independently plug into the Abstract elements. I’ve tried my best to redesign the above diagram to convey the three different planes.

While the lines cross because these diagrams are not a planar graph, notice that the three sets of cohesive colors never interact with one another. They have no dependencies or knowledge of one another. They peacefully coexist.

Each colored set of cohesive elements are planar within their own plane where the Configurer creates and injects the Concrete Factory into the Business Logic. The Business Logic invokes the Concrete Factory abstractly to create the Concrete Dependencies it needs to resolve its abstract Dependencies. Regardless of Factory context, they all follow the same pattern structure:

Abstract Factory isn’t messy. It’s quite neat and orderly in three-dimensional space. It only becomes messy when the three-dimensional design is projected onto two-dimensional space.

Summary

Abstract Factory may not be the simplest design pattern, but once you’ve seen it in action, it becomes one of the most versatile. From test configuration to production deployment, it helps you keep your code consistent, decoupled, and adaptable.

Next time your application needs to support swappable modules, multiple environments, or consistent object families, reach for Abstract Factory. Just remember to build it layer by layer—and keep the messy wiring down in the dirt where it belongs.

References

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern via Wikipedia

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern via SourceMaking

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern via RefactoringGuru

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern via Baeldung

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern blog by Srishti Prasad

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern in Java blog by Pankaj Kumar

- The Abstract Design Pattern with Examples – Solving the Design Pattern Conundrum blog by Team Blazeclan

- Understanding Design Patterns: Abstract Factory blog by Carlos Caballero

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern video by Scott Bain

- The Abstract Factory Pattern Explained and Implemented video by Geekific

- Abstract Factory Pattern – Design Patterns (ep 5) video by Christopher Okhravi

- Abstract Factory Design Pattern in detail video by Daily Code Buffer

- Abstract Factory Pattern (Gang of Four) video by Wes Doyle

- Google Search: Abstract Factory Design Pattern

- Google Video Search: Abstract Factory Design Pattern Video

Complete Demo Code

Here’s the entire implementation up to this point as one file. Copy and paste it into a Java environment and execute it. If you don’t have Java, try this Online Java Environment. Add more tests. Play with the implementation. Refactor some of the code. Copy and paste the code into Generative AI for analysis and comments.

import java.util.*;

public class AbstractFactory {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Test.test();

System.out.println();

Warrior rifleman = new Warrior(new RifleWeaponSystem());

rifleman.fire();

System.out.println();

Warrior antiTankSoldier = new Warrior(new BazookaWeaponSystem());

antiTankSoldier.fire();

System.out.println();

Warrior archer = new Warrior(new ArcheryWeaponSystem());

archer.fire();

}

}

///////////// ABSTRACT FRAMEWORK SOFTWARE UNDER TEST //////////////////

interface LauncherSystem {

Launcher acquireLauncher();

Projectile acquireProjectile();

}

interface Launcher {

int getProjectileCapacity();

void load(Projectile projectile);

void aim();

void launch();

}

interface Projectile {

String getType();

}

class Warrior {

private final LauncherSystem launcherSystem;

public Warrior(LauncherSystem launcherSystem) {

this.launcherSystem = launcherSystem;

}

public void fire() {

Launcher launcher = launcherSystem.acquireLauncher();

for (int i = 0; i < launcher.getProjectileCapacity(); i++) {

launcher.load(launcherSystem.acquireProjectile());

}

for (int i = 0; i < launcher.getProjectileCapacity(); i++) {

launcher.aim();

launcher.launch();

}

}

}

///////////// RIFLE SYSTEM //////////////

class RifleWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Rifle();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new Bullet();

}

}

class Rifle implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 6;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Load %s into rifle\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.println("Aim down rifle barrel");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Squeeze rifle trigger to shoot %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class Bullet implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "Bullet";

}

}

///////////// BAZOOKA SYSTEMS //////////////

class BazookaWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Bazooka();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new BazookaShell();

}

}

class Bazooka implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 1;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Load %s into bazooka\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.println("Aim down bazooka site");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Squeeze bazooka trigger to launch %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class BazookaShell implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "BazookaShell";

}

}

///////////// ARCHERY SYSTEMS //////////////

class ArcheryWeaponSystem implements LauncherSystem {

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new Bow();

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new Arrow();

}

}

class Bow implements Launcher {

private Projectile projectile;

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 1;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

System.out.format("Notch %s into the bow string\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void aim() {

System.out.format("Pull back bow string and aim down %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

@Override

public void launch() {

System.out.format("Release bow string to launch %s\n", projectile.getType());

}

}

class Arrow implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "Arrow";

}

}

////////////// TEST DOUBLES /////////////////

class LauncherSystemTestDouble implements LauncherSystem {

private List<String> actions;

public LauncherSystemTestDouble(List<String> actions) {

this.actions = actions;

}

@Override

public Launcher acquireLauncher() {

return new LauncherTestDouble(actions);

}

@Override

public Projectile acquireProjectile() {

return new ProjectileTestDouble();

}

}

class LauncherTestDouble implements Launcher {

private List<String> actions;

private Projectile projectile;

public LauncherTestDouble(List<String> actions) {

this.actions = actions;

}

@Override

public int getProjectileCapacity() {

return 2;

}

@Override

public void load(Projectile projectile) {

this.projectile = projectile;

actions.add(String.format("Load: %s", projectile.getType()));

}

@Override

public void aim() {

actions.add("Aim LauncherTestDouble");

}

@Override

public void launch() {

actions.add(String.format("Launch %s", projectile.getType()));

}

}

class ProjectileTestDouble implements Projectile {

@Override

public String getType() {

return "ProjectileTestDouble";

}

}

/////////////// TESTS ////////////////

class Test {

public static void test() throws Exception {

testWarrior();

System.out.println("End Tests");

}

private static void testWarrior() throws Exception {

// Given

List<String> actions = new LinkedList<>();

LauncherSystem launcherSystem = new LauncherSystemTestDouble(actions);

Warrior warrior = new Warrior(launcherSystem);

// When

warrior.fire();

// Then

assertEquals("[Load: ProjectileTestDouble, Load: ProjectileTestDouble, Aim LauncherTestDouble, Launch ProjectileTestDouble, Aim LauncherTestDouble, Launch ProjectileTestDouble]", actions.toString());

}

private static void assertEquals(String expected, String actual) throws Exception {

if (!expected.equals(actual)) {

System.out.format("expected=%s, actual=%s\n", expected, actual);

throw new Exception();

}

}

}