Prototype Design Pattern; Acquisition Without Class Knowledge

Prototype is not about cloning objects. It’s about surviving change without rewriting factories.

Introduction

In most mainstream Object-Oriented programming languages, objects can only be instantiated through their constructors, which depends upon and requires knowledge of their concrete class types. Dependency Injection shifts the burden from the application code to a Configurer, but it doesn’t eliminate class dependency and knowledge. It just relocates it.

The Creational Design Patterns provide several techniques that encapsulate class details from the application or client code acquiring the object. However, the creation pattern mechanism itself depends upon and has knowledge of the class type. That knowledge becomes a maintenance hotspot as systems grow.

The problem is not object creation; it’s ongoing system evolution.

Prototype is our final creational design pattern. It has a trick up its sleeve. It doesn’t depend upon or have knowledge of class types. Prototype doesn’t acquire an object via a constructor directly. It acquires an object from an existing object of the type it desires. The constructor call has not disappeared. Prototype has found another place to stash it, that is, within the concrete class itself.

Interpreter Grammar and Parser, Revisited

Prototype is easiest to understand in systems where new types are added over time, often by people who did not write the original framework. My Interpreter/DSL project is a concrete example of this pressure.

The Production Example Grammar for my Interpreter Design Pattern Series was basic. The Scanner extracted Keywords and Symbols as alphanumerics, but it didn’t provide any context other than determining an identifier. The Parser determined the semantic context.

Alphanumeric identifiers could be one of three categories in my Project Example’s Domain Specific Language (DSL). The parser checked for each category in succession:

- Keywords - Such as:

if,else,and,orandnot. These were identified and hardcoded directly in the parser. New keywords were added very infrequently, but a few were subsequently added. I was usually able to add them to the parser implementation easily. - Variable/Function Names - These were entities defined within the script executing the DSL. They were equivalent to variables or function names in most programming languages. When a new identifier was defined in the script, it along with its definition was added to a symbol table, which the parser subsequently would query. If a name was found in the symbol table then its definition would be used.

- Class Names - The DSL defined a structural framework organizing behavior across a set of objects identified by their class names. Most of the real work resided in the classes. The DSL was the structural framework that organized objects of the class types in different configurations allowing a relatively small set of elements to exhibit a near infinite number of behaviors based upon how they were configured. The parser needed to create object instances for those class types. A Factory would have sufficed, as seen in the

switchstatement in Factory Method, but that would mean that when a new class type was added, I would have had to update theswitchstatement in the factory used by the parser. I wanted to avoid updating the parser factory each time we added a class type, and I believe we added at least 50 class types over the lifespan of the project. I used Prototype to acquire class named objects, and I never had to update the parser when we added a new class type.

Prototype

Prototype is completely different than the other Creational Design Patterns. If the other creational design patterns are fingers, then Prototype is a thumb.

The Prototype Thumb is different from the other creational pattern Fingers in that it does not require:

- A static factory

- Switch/map of types

- Centralized creation logic updates

- Constructor calls in the creation mechanism

Factory, Revisited

Let’s briefly review the basic Factory pattern. The client acquires a Feature instance without knowing the class type. For example, when the client acquires a Feature instance using the FeatureFactory as such:

Feature feature = FeatureFactory.acquire();

the client is encapsulated from the concrete class that implements Feature:

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

FeatureImpl() {}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

// Does something

}

}

class FeatureFactory {

public static Feature acquire() {

return new FeatureImpl();

}

}

If a new Feature implementation class is introduced, this won’t affect the client, but updates will be needed for FeatureFactory.

Factories encapsulate which class is created; Prototype eliminates the need to even know what the class types are.

Basic Prototype

Prototype doesn’t use a static method to acquire an object, which is the primary mechanism in most of the other Creational Design Patterns. Prototype acquires an object from a breeder object by having it clone itself. Other creational design patterns encapsulate the constructor by placing the call to new() within a class static method. Prototype encapsulates the constructor by placing the call to new() within a non-static method accessed via an object instance of that class.

The client code would acquire a Feature object using Prototype as follows:

Feature breeder = // Reference To Be Determined

Feature feature = breeder.acquire();

It’s a little disorienting at first, but it’s not complicated. A few lines of code demonstrate the fundamental principle.

interface Feature {

Feature acquire();

void doSomething();

}

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

FeatureImpl(){}

@Override

public Feature acquire() {

return new FeatureImpl();

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

// Does something

}

}

The constructor is not called from a Factory static method, which is often the case with the other creational patterns. With Prototype, the constructor is in an object method, which can be invoked from an object of the given type, but it often returns a reference to its interface definition, thereby maintaining encapsulation.

The Name

I’ve never been much of a fan of the name Prototype. It’s too easy to confuse it with an early throwaway proof-of-concept prototype implementation. I think that Clone, Copy or Breeder would have been better names. But Prototype is the name chosen by the Gang of Four (GoF), so it’s the one I’ll be using.

Traditionally, each Prototype concrete class implements the clone() or copy() method as it sees fit. These method names imply that the concrete class will make a copy of itself. While that’s an option, it’s not a requirement. This is one of the reasons while I prefer the method name acquire(). It does not convey the creational mechanism as clone() or copy() would. From the client’s point of view, nothing is being cloned. Something is being acquired. The GoF emphasized cloning mechanics; I emphasize acquisition semantics.

Additionally, clone is a reserved word in Java, and using it adds some language baggage that I prefer to avoid. Maybe an even better name for this pattern could have been Offshoot or Sprout by borrowing botany terms.

Acquisition Via Object

Prototype is more of a contract declaration than an implementation. It declares that a class that implements the interface must provide a method that returns an instance of the interface. It doesn’t dictate how the class creates the object instance.

The concrete class has several options to implement acquire(). I’ll provide several examples. Each will implement one of the following interface methods, but not both. This is a conceptual interface sketch, not a literal Java interface:

Feature {

Feature acquire();

Feature acquire(State state);

}

Returns the Object Itself

This technique returns the source object itself.

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

public Feature acquire() {

return this;

}

}

This is the most simple version, but it only works when FeatureImpl is an immutable Value Object (TBD), such as a Singleton.

By immutable value object, I mean an object whose observable state cannot change after construction. It holds no mutable fields, exposes no setters, and does not represent an identity that evolves over time. In these cases, returning this is safe because sharing the instance cannot introduce cross-client interference. If mutation is possible, even indirectly, this technique should be avoided.

Returns the Object via Default Constructor

This technique returns a new default object.

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

private FeatureImpl() {}

public Feature acquire() {

return new FeatureImpl();

}

}

A new object is instantiated using the default constructor. This will probably suffice in many cases.

Returns the Object via Copy Constructor

This technique returns a new copied object.

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

private FeatureImpl(FeatureImpl feature) {

// Copy attributes from feature to this new object.

}

public Feature acquire() {

return new FeatureImpl(this);

}

}

This is the closest implementation to what’s used in traditional Prototype presentations.

There are two considerations when using the copy constructor. Are the attributes copied via a shallow copy or deep copy? This will depend upon the context, but I suspect that in most Prototype implementations the deep copy will be desired. A shallow copy will return a reference to the attribute, whereas a deep copy will return a copy of the attribute.

Returns the Object with State

This technique returns a new object with state.

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

private State state;

private FeatureImpl(State state) {

this.state = state;

}

public Feature acquire(State state) {

return new FeatureImpl(state);

}

}

This allows the newly created object to have its own state. State is a placeholder type. In an actual implementation, it could be a String, another class or even a list of arguments.

Returns the Object with State via Copy Constructor

This is a hybrid of the State and Copy Constructor techniques shown above.

class FeatureImpl implements Feature {

private State state;

private FeatureImpl(FeatureImpl feature, State state) {

// Copy attributes from feature to this new object.

this.state = state;

}

public Feature acquire(State state) {

return new FeatureImpl(this, state);

}

}

This is the technique that I’ll use in the Use Case.

Acquisition Summary

| Acquisition Technique | How It Works | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

Return this (Self) |

acquire() returns the breeder object itself, not a new instance. |

When the object is immutable, stateless, or a true value object. Also appropriate for Singleton-like semantics where sharing is intentional and safe. |

| Default Constructor | acquire() creates a new instance using the default constructor. |

When the object has no meaningful internal state, or when each acquired instance should start from a clean, identical baseline. This is the simplest and most common Prototype form. |

| Copy Constructor | acquire() creates a new instance by copying the breeder’s fields. |

When the breeder acts as a template and the new object should inherit its configuration. Use a deep copy when mutable fields are involved. |

| State-Based Acquisition | acquire(state) creates a new instance initialized with external state. |

When the client must supply context-specific data at acquisition time, and the breeder primarily defines behavior, not configuration. |

| Copy + State Hybrid | acquire(state) copies the breeder and then applies additional state. |

When the breeder provides a default configuration, but each acquired instance needs customized runtime state. Common in DSLs, parsers, and rule engines. |

Prototype Registry

But something is still amiss. We have a bit of a chicken and egg problem. Prototype uses objects to make copies of objects. We still need that first seed object as the breeder. My example above only provided a comment // Reference To Be Determined. Where does it come from and how do clients access it?

Let’s add a new concept: Prototype Registry. A Prototype Registry contains a collection of Prototype objects, which can be copied via their acquire method. Each Prototype object in the registry has a key identifier, such as a String name. When the client wants an object, it asks the registry to acquire one by name. The registry gets the object that matches the name and returns an acquired copy of the object.

There are several features and caveats to this Prototype Registry:

- The key identifier does not need to match the breeder object’s class type name.

- The key identifier does not need to be a name. Any set of key attributes that uniquely identify a breeder object will suffice.

- Multiple key identifiers can map to a breeder object of the same class type.

- A unique key should map to no more than one breeder object.

- A queried key may not be registered. The registry will need to define how it will respond, which could be a returned

Optional,nullor a thrown Exception. The client will need to accommodate these Breeder Not Found cases.

The structure is almost identical to Flyweight, except that instead of returning the key matching object, which is what Flyweight does, Prototype returns an acquired copy of the matching object.

Examples for all of this will be forthcoming in the Design and Implementation.

Prototype Registry Lifecycle

A Prototype Registry is not just a data structure; it is a lifecycle decision. When and how breeders are registered determines the flexibility, safety, and testability of the system. Below are several common lifecycle strategies, each with tradeoffs.

| Registry Lifecycle Strategy | How Registration Occurs | Best Suited For | Key Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Startup-Time Registration | All Prototypes are registered during application startup and remain fixed for the lifetime of the application. | Stable systems, core infrastructure, production deployments. | Least flexible; adding new Prototypes requires restart or redeploy. |

| Bootstrap / Initializer | A dedicated bootstrap class explicitly registers all Prototypes in a controlled sequence. | Medium to large systems; Java applications needing deterministic registration. | Centralized but can grow large; requires manual maintenance. |

| Module / Plugin-Based | Each module or plugin registers its own Prototypes when loaded or activated. | Extensible frameworks, plugin architectures, optional features. | Registration order and lifecycle must be carefully managed. |

| Dependency Injection–Assisted | A DI container creates and registers Prototypes as part of configuration or wiring. | Applications already using DI frameworks; testable, configurable systems. | Adds framework coupling; registry behavior depends on container lifecycle. |

| Test-Time Registration / Override | Prototypes are registered or replaced during test setup. | Unit, integration, and scenario-based testing. | Must ensure registry isolation between tests. |

| Dynamic Runtime Registration | Prototypes are added or removed while the system is running. | Long-running systems, rule engines, live-reconfigurable platforms. | Highest complexity; requires strict synchronization and invariant enforcement. |

| Controlled Global Registry | Registry exists as shared global state accessed via well-defined APIs. | Most Prototype implementations regardless of lifecycle choice. | Global state must remain intentional, documented, and constrained. |

Prototype Registry Allows More Granularity

A Prototype Registry is a registry of objects. It’s not a registry of classes. That means that the same class can be represented as different registered objects that vary in behavior based upon distinguishing attributes or their configuration. Prototype Registry would work well with Composable Design Patterns, since their behavior is defined via the assembly of a set of objects. The named root of the assembled objects can be registered. I’ll provide an example of this in the Use Case. While this is technically possible with some creational patterns, such as Factory, it feels more natural within a Prototype Registry.

Acquisition from this type of Prototype Registry should probably return a reference to the breeder object or acquire a new one using the copy constructor since its behavior is based upon its attributes.

This type of Prototype Registry might work well in a game. Magic: The Gathering consists of different types of cards, but for the most part, they vary based upon different values for the same set of attributes. Board Wargames, such as Panzer Blitz, also come to mind, where each piece’s abilities depends upon its attributes for mobility, offense, defense, etc.

Prototype/Prototype-Registry Design and Implementation

Let’s walk through a Prototype and Prototype Registry design and implementation one step at a time.

Feature

Feature declares a contract interface:

The implementation is the same as the examples above, minus acquire(), which will be in the next portion:

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

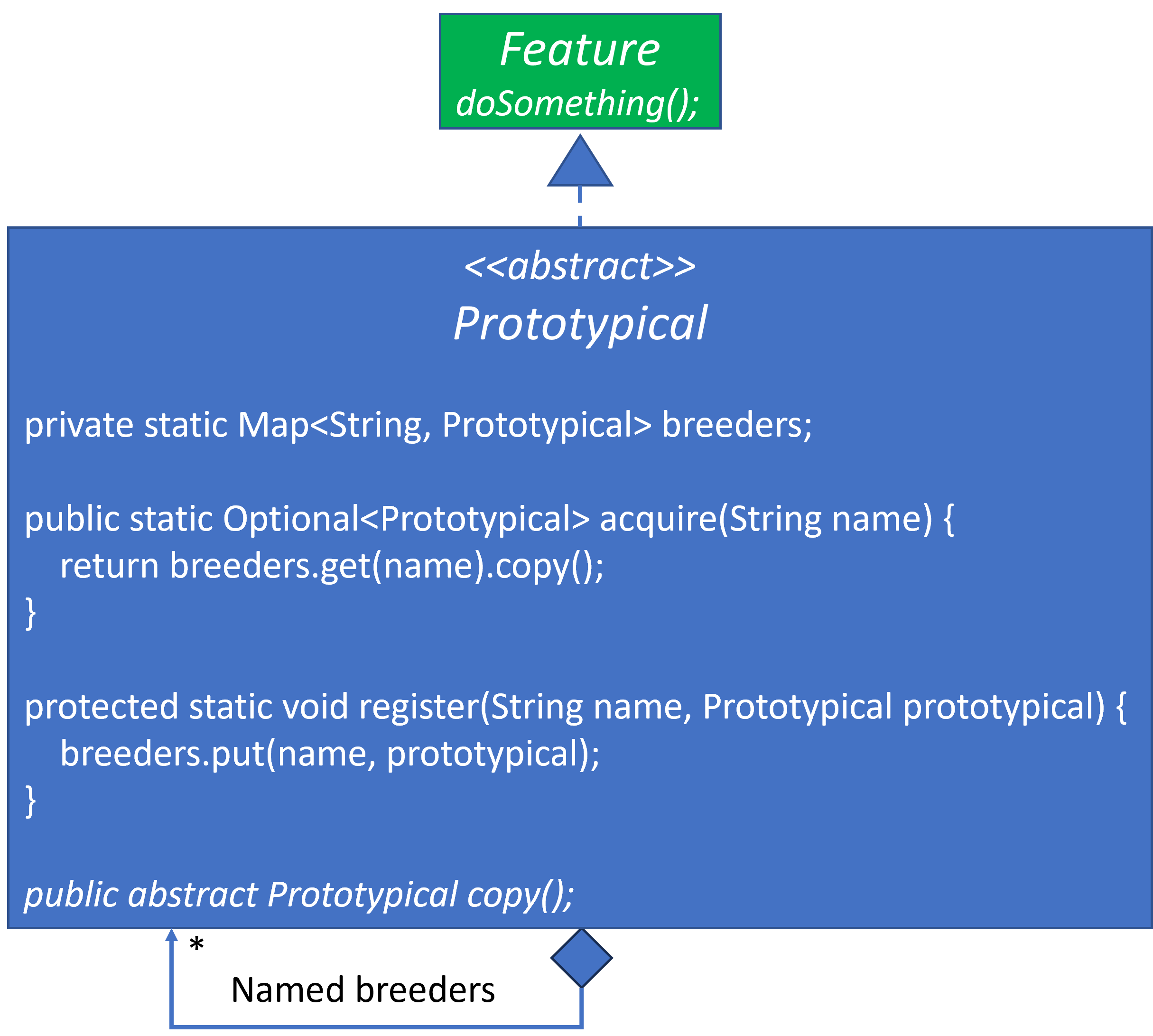

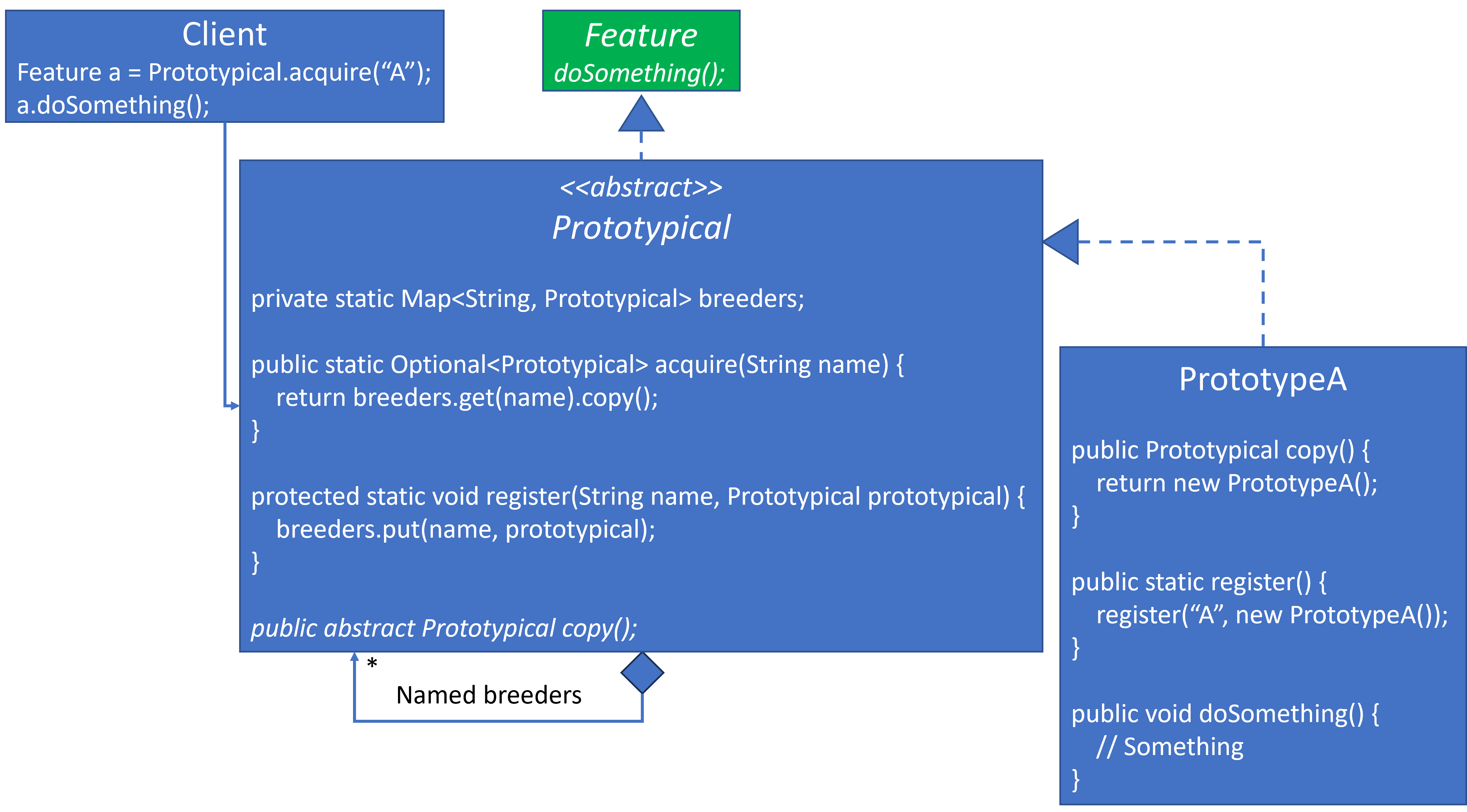

Prototypical

Prototypical implements Feature. Just as Flyweight contained a static repository within it, Prototypical contains a static repository within it too. Prototypical is both a Prototype and a Registry façade. Prototypical plays two roles: it defines the prototype contract and hosts the registry that manages initial breeders. I know this violates the Single Responsibility Principle, but we’re not bound to it. Learn the rules, and then break the rules.

register(String name, Prototypical prototypical) places a named Prototypical breeder into the breeders.

acquire(String name) searches for the breeder by name in the repository. If found, it returns an acquired version of the object.

Prototype has another trick up its sleeve. Once a client has a Prototypical object, it can acquire() a new object from the acquired object, from which another object can be acquired, etc. There is no limit to how many new objects can be acquired regardless of how many generations they have descended from their repository ensconced initial breeder ancestor. This is a feature that other creational design patterns do not possess. I will feature this chained acquisition in the Use Case.

Chained acquisition allows objects to act as localized factories for their own variants. Once acquired, an object can refine or specialize itself further without consulting the registry again. This enables hierarchical or progressive specialization, something static factories and builders cannot do without reintroducing class knowledge.

Since there may not be a registered breeder, I have defined acquire(String name) to return an Optional<Prototypical> if a breeder is not found.

abstract class Prototypical implements Feature {

private static final Map<String, Prototypical> breeders = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

public static Optional<Prototypical> acquire(String name) {

Prototypical breeder = breeders.get(name);

return breeder != null ? Optional.of(breeder.acquire()) : Optional.empty();

}

protected static void register(String name, Prototypical breeder) {

if (breeders.containsKey(name)) throw new IllegalStateException("A breeder named '" + name + "' has already been registered");

breeders.put(name, breeder);

}

public abstract Prototypical acquire();

}

At this point, the core functionality of the Prototype/Prototype-Repository pattern is complete. Notice that there are no concrete classes. There’s only an interface and an abstract class. new() is not called. If new classes are added to the design, they are registered to the repository.

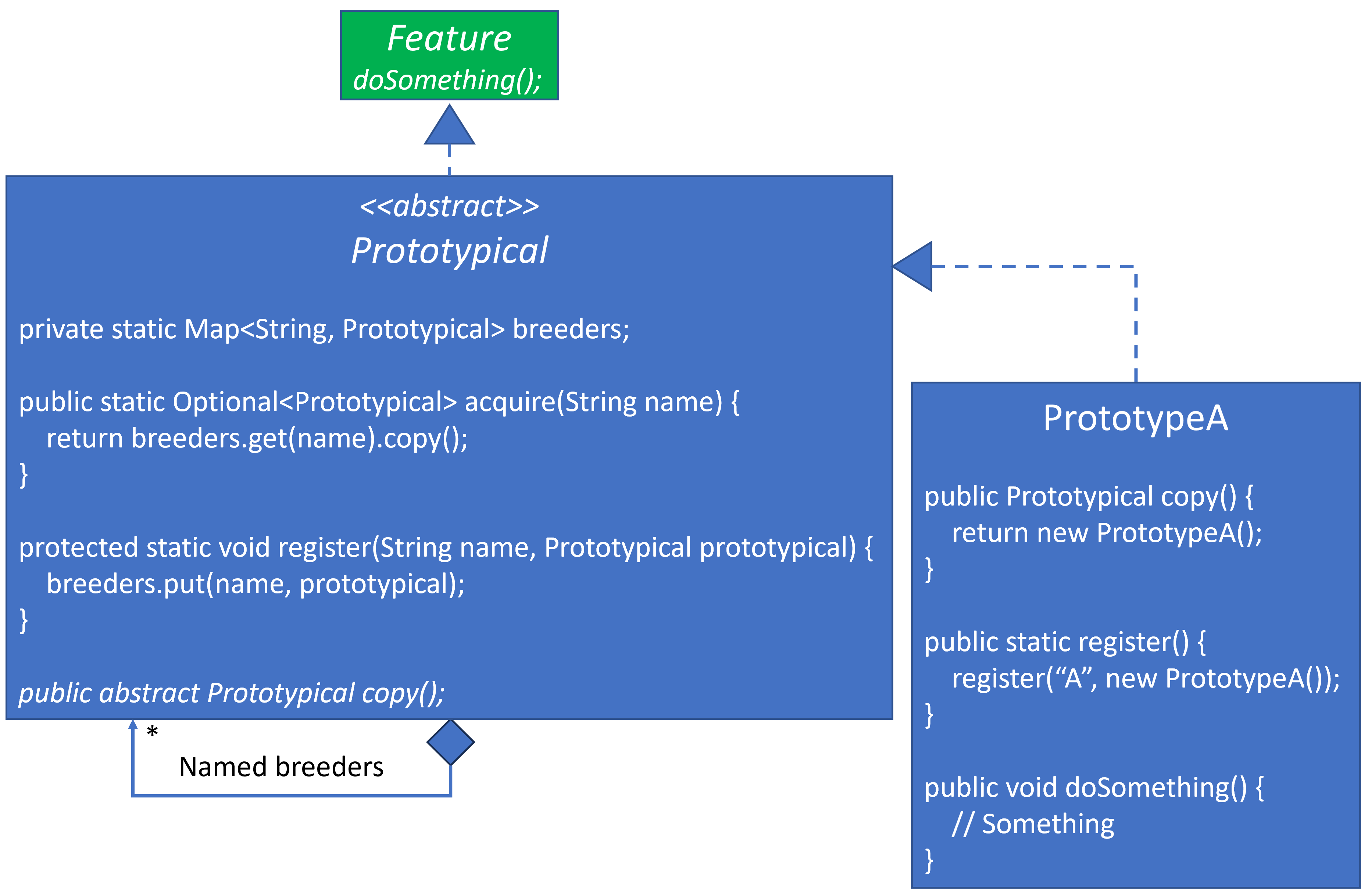

Concrete Prototype Classes

While the core functionality is complete, it needs a few more elements. Concrete classes need to implement Prototypical and be registered into Prototypical.

The diagram only has enough room to represent one concrete class, but the code sample shows how we can declare more classes. Each class registers an instance of itself along with its chosen name, which does not need to be the class name. It just needs to be unique in the registry. Rather than class self-registration, a class administrator could create the breeder instance and register it as well.

We can call register() from within a static block in C++, which will register an instance when loaded. Java will not do this. A similar static block will only register the instance when the class is referenced, which is probably too late. Therefore, an external entity must register Prototypes in Java.

class PrototypeA extends Prototypical {

private PrototypeA() {}

@Override

public Prototypical acquire() {

return new PrototypeA();

}

public static void register() {

register("A", new PrototypeA());

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.println("PrototypeA does something that's A specific");

}

}

class PrototypeB extends Prototypical {

private PrototypeB() {}

@Override

public Prototypical acquire() {

return new PrototypeB();

}

public static void register() {

register("B", new PrototypeB());

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.println("PrototypeB does something that's B specific");

}

}

Clients

Here is the complete design with Clients. I realize the diagram is inconsistent in its use of Optional. I had to make a few accommodations due to space constraints.

Here’s the implementation, which registers the Prototypes statically and acquires them. I went all in with Java’s Optional syntax. I’ve added an unregistered type, C, to demonstrate that the repository may not have what you desire:

public class PrototypeDemo1 {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

for (String name : List.of("A", "B", "C")) {

FeatureProvider.acquire(name).ifPresentOrElse(

Feature::doSomething,

() -> System.out.println("Feature not found for name=" + name));

}

}

static { // Register the Prototypes. NOTE: C has not been registered intentionally for the demo.

PrototypeA.register();

PrototypeB.register();

// PrototypeA.register(); // This will throw an IllegalStateException since a Prototype named A has already been registered.

}

}

Review

This implementation is close to how I resolved class names with my Parser. When we added a new functional class, we added a static blocked registration. It was in C++, so registration happened automatically at start up. When the parser encountered an identifier for the class, the Prototype Registry would find the registered breeder and return a copy of it.

Prototype Use Case

The next blog will feature a Prototype Use Case.

When Not to Use Prototype

Prototype is not a default choice. If your system has a closed set of types, changes infrequently, or prioritizes simplicity over extensibility, a Factory or Builder will usually be clearer and easier to reason about. Prototype earns its complexity only when the cost of change dominates the cost of indirection.

Summary

Prototype is not about cloning objects; it is about decoupling object acquisition from concrete class knowledge. By allowing objects to create other objects of their own kind, Prototype eliminates the need for centralized creation logic that must be updated as systems evolve.

This power comes with responsibility. Prototype introduces a registry, lifecycle decisions, and potential global state. Used carelessly, it can obscure system behavior. Used deliberately, it enables architectures that remain stable even as new types are introduced.

Choose Prototype when the cost of change outweighs the cost of indirection.

References

- Wikipedia Prototype Design Pattern

- Source Making Prototype Design Pattern

- Refactoring Guru Prototype Design Pattern

- Prototype Pattern in Java - Baeldung blog by Vivek Balasubramaniam

- Simplify Your JavaScript Code With Prototype Design Pattern In JavaScript - Blog by Vishnu Prasath

- C# Prototype Design Pattern - Blog by dofactory.com

- What is the Prototype Design Pattern? - Video by NeetCodeIO

- Prototype Pattern in C++ (clone) - Creational Design Patterns - Video by Mike Shah

- Prototype - Design Patterns in 5 minutes - Video by levonog

- Prototype Design Pattern Tutorial - Video by Derek Banas

- and for more, Google: Prototype Design Pattern

Complete Demo Code

Here’s the entire implementation up to this point as one file. Copy and paste it into a Java environment and execute it. If you don’t have Java, try this Online Java Environment. Play with the implementation. Copy and paste the code into Generative AI for analysis and comments.

Complete Prototype and Prototype Registry Implementation

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

public class PrototypeDemo1 {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

for (String name : List.of("A", "B", "C")) {

FeatureProvider.acquire(name).ifPresentOrElse(

Feature::doSomething,

() -> System.out.println("Feature not found for name=" + name));

}

}

static { // Register the Prototypes. NOTE: C has not been registered intentionally for the demo.

PrototypeA.register();

PrototypeB.register();

// PrototypeA.register(); // This will throw an IllegalStateException since a Prototype named A has already been registered.

}

}

interface Feature {

void doSomething();

}

class FeatureProvider {

private FeatureProvider() {}

public static Optional<Prototypical> acquire(String name) {

return Prototypical.acquire(name);

}

}

// No switch, no reflection, no class knowledge.

abstract class Prototypical implements Feature {

private static final Map<String, Prototypical> breeders = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

public static Optional<Prototypical> acquire(String name) {

Prototypical breeder = breeders.get(name);

return breeder != null ? Optional.of(breeder.acquire()) : Optional.empty();

}

protected static void register(String name, Prototypical breeder) {

if (breeders.containsKey(name)) throw new IllegalStateException("A breeder named '" + name + "' has already been registered");

breeders.put(name, breeder);

}

public abstract Prototypical acquire();

}

class PrototypeA extends Prototypical {

private PrototypeA() {}

@Override

public Prototypical acquire() {

return new PrototypeA();

}

public static void register() {

register("A", new PrototypeA());

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.println("PrototypeA does something that's A specific");

}

}

class PrototypeB extends Prototypical {

private PrototypeB() {}

@Override

public Prototypical acquire() {

return new PrototypeB();

}

public static void register() {

register("B", new PrototypeB());

}

@Override

public void doSomething() {

System.out.println("PrototypeB does something that's B specific");

}

}