Consumer-Driven Contract Testing

Giving the consumer exactly what they asked for

Introduction

Bob Martin tells a story on the Clean Coders Podcast, starting at 39:38, of a project he had worked on several decades previously. The customer paid Bob’s shop a run rate, which was about half what they wanted. It was enough to keep the doors open and the lights on, but not much after that.

The customer also paid a completion bonus upon delivery for each of their requested 36 features. How would the customer know that a feature was accurate and complete? What if Bob’s team delivered a feature in good faith, but the customer refused to pay because it wasn’t exactly what they expected?

The feature requirements weren’t specified traditionally. Bob’s customer provided Acceptance Criteria from which Bob’s team created Acceptance Tests. When the Acceptance Tests for a feature passed, the team knew they could deliver the feature to the customer and receive payment. The customer couldn’t claim that the delivered feature wasn’t what they expected or needed, since the team had a repeatable proof via the Acceptance Tests that the feature worked as specified by the customer.

They gave the customer exactly what they asked for.

Consumer-Driven Contract Testing

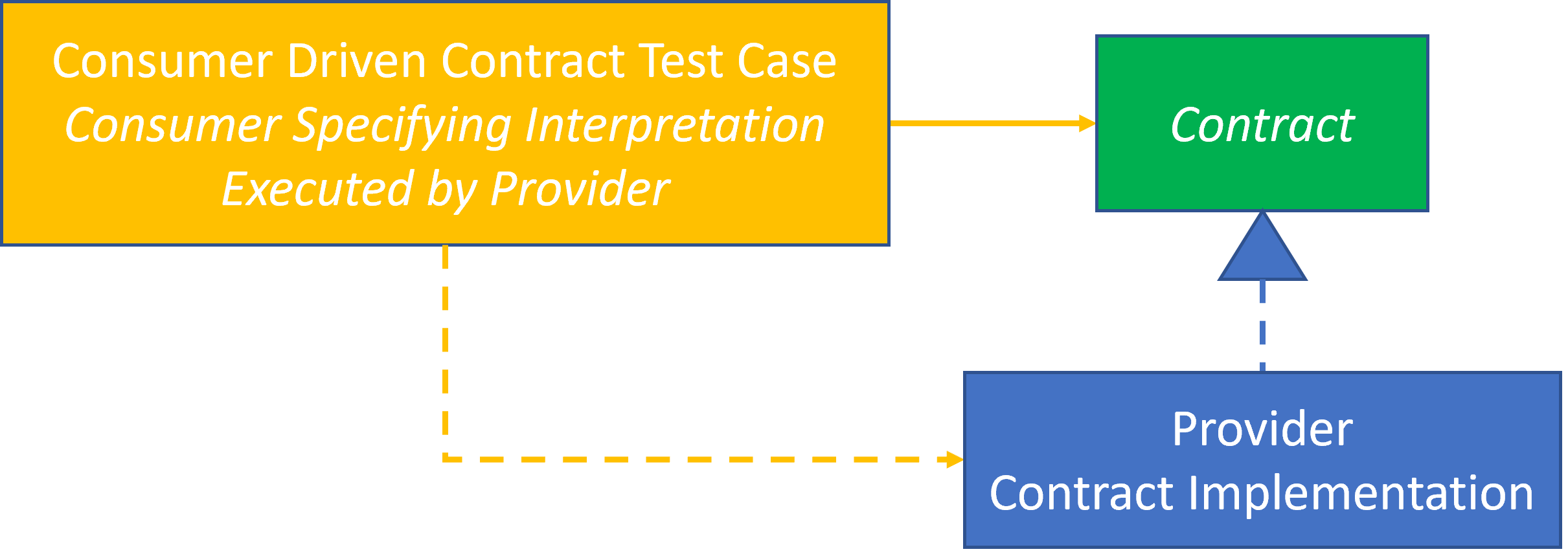

Bob’s story is closely related to Consumer-Driven Contract Testing (CDC Testing), which can be thought of as the intersection of Contracts and Acceptance Testing. CDC Testing ensures that the obligations and expectations defined in a Contract are honored by the Provider via the Consumer-provided tests that specify the Consumer’s dependencies upon the Contract’s obligations and expectations. Providers only release code that satisfies those Consumer-provided Contract specification tests.

Microsoft describes CDC Testing in their Engineering Fundamentals Playbook as:

Consumer-Driven Contract Testing (or CDC for short) is a software testing methodology used to test components of a system in isolation while ensuring that provider components are compatible with the expectations that consumer components have of them.

CDC tests interactions between components in isolation using Test Doubles that conform to a shared understanding documented in a “contract”. Contracts are agreed between consumer and provider, and are regularly verified against a real instance of the provider component. This effectively partitions a larger system into smaller pieces that can be tested individually in isolation of each other, leading to simpler, fast and stable tests that also give confidence to release.

CDC Testing in a Nutshell

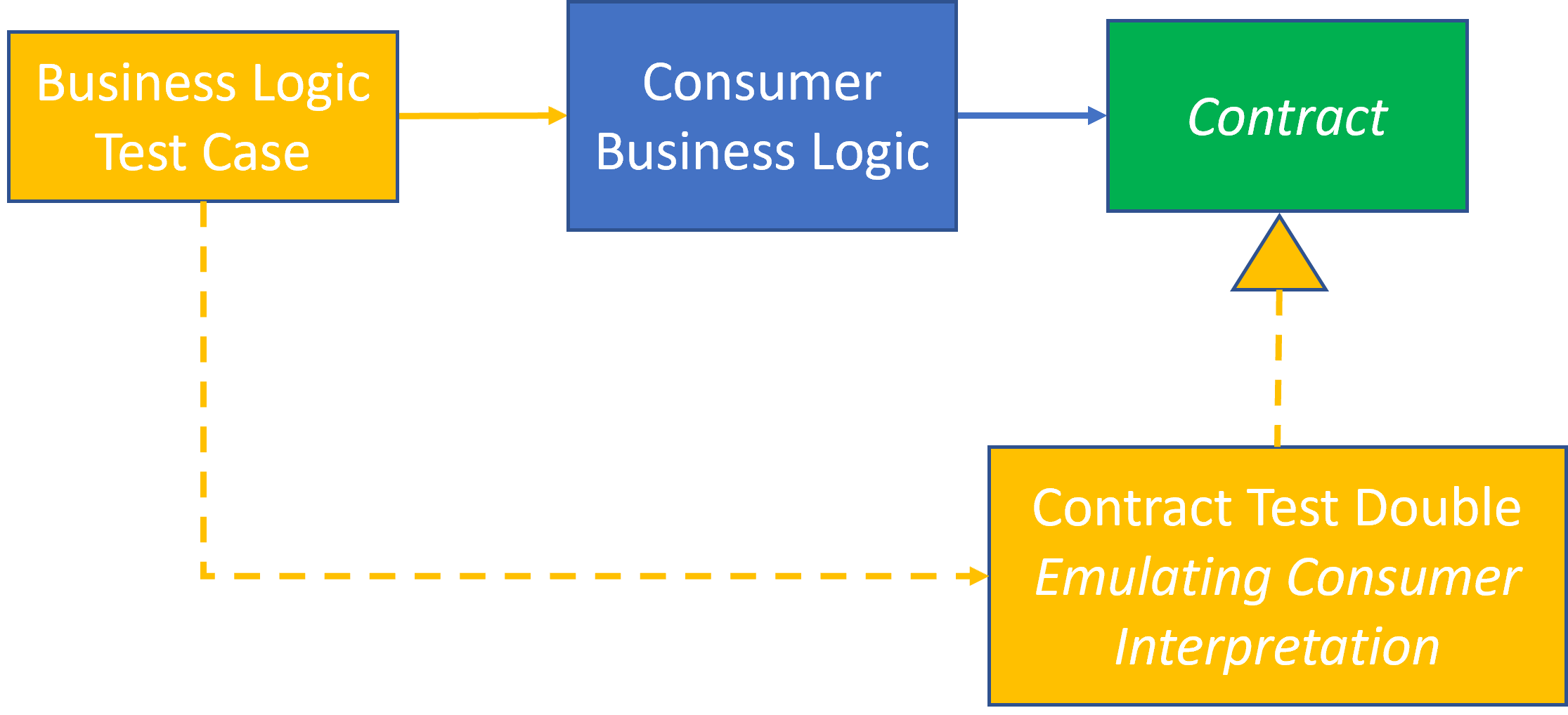

With CDC Testing, the Consumer provides tests that specify the Contract behaviors they expect. The Producer doesn’t release their code until the Consumer-provided tests pass.

It’s still the responsibility of the Consumer to ensure that their Test Doubles emulate the Contract, but now the Consumer has the reassurance that the Provider honors their interpretation of the Contract.

The Contract is Core

Contracts are Stable/Fixed Elements within a design where they form Natural Boundaries among other software elements. Contracts define Seams that allow us to decouple a design into chunks of cohesive elements. This facilitates parallel development among different developers or teams who can test their code without being tightly coupled to the implementations provided by the other teams.

Decoupled testing is supported by injecting Test Doubles within a test to resolve Contract dependencies rather than depending upon the production implementation.

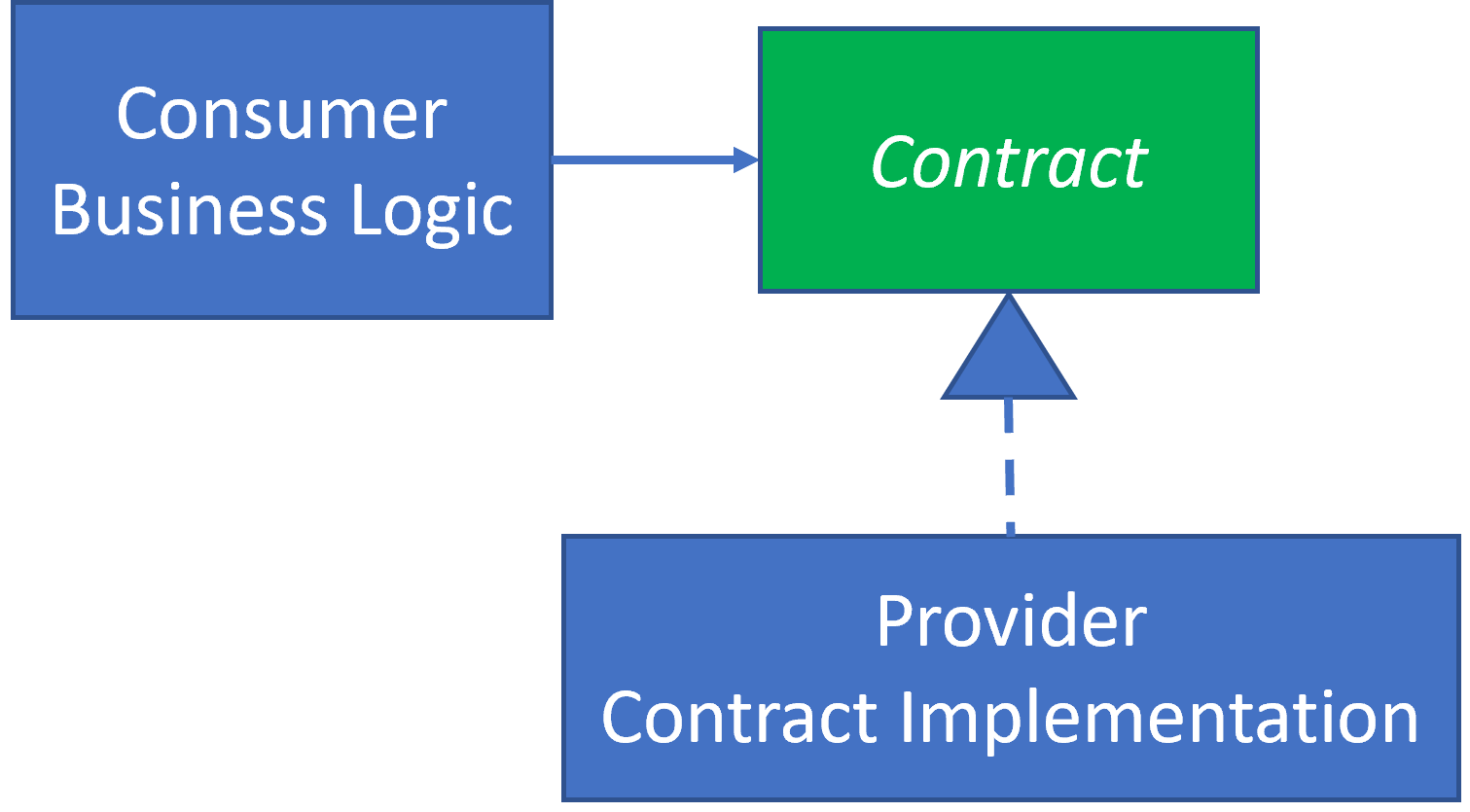

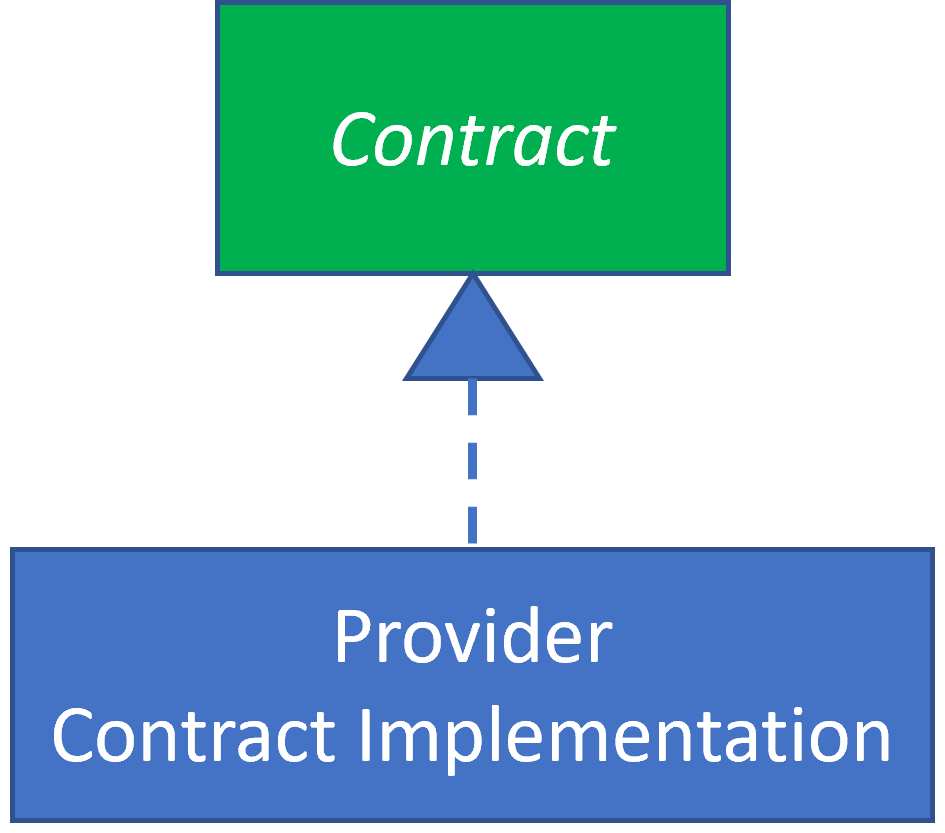

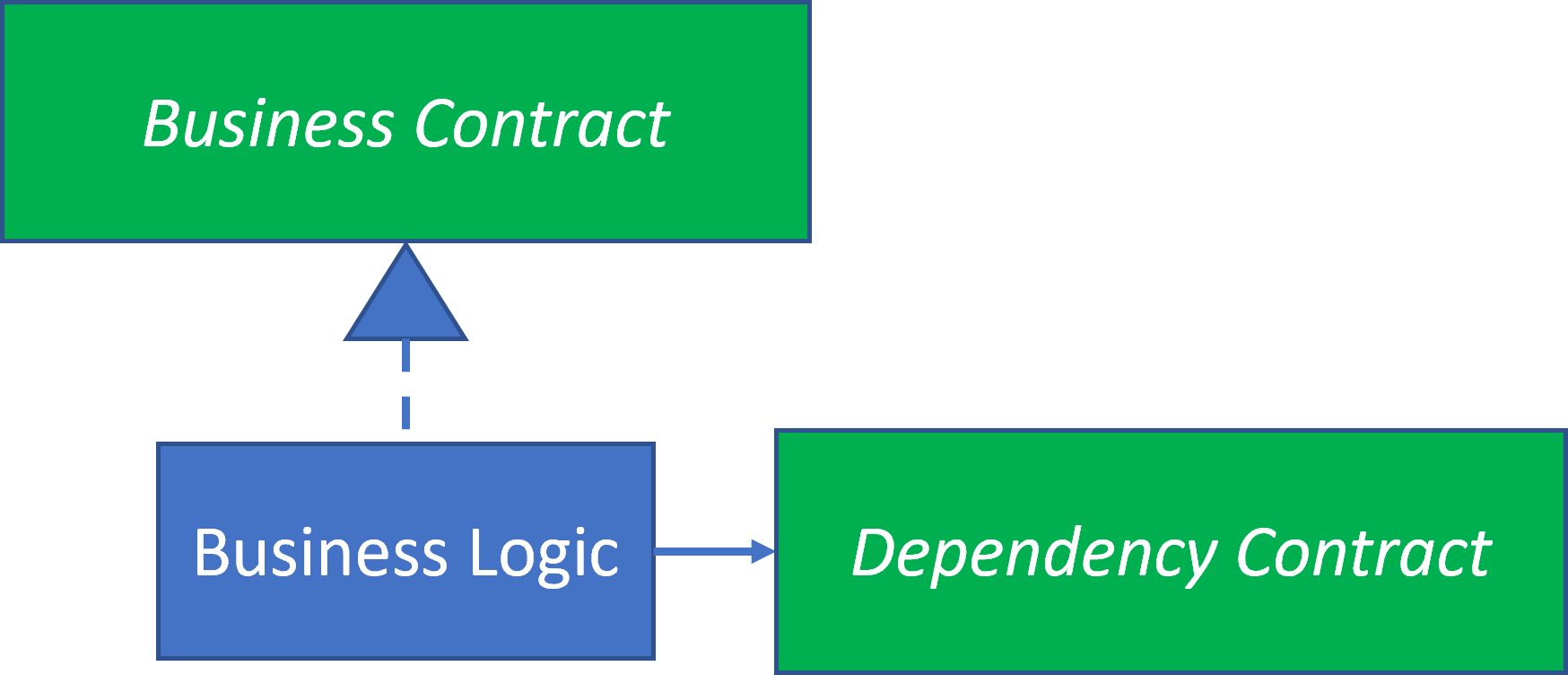

The Basic Contract Pattern

Let’s consider this simple pattern where Consumer Business Logic delegates to the Contract, which is implemented by the Provider Contract Implementation. This pattern repeats in almost every design.

All arrows, indicating the flow of dependency and knowledge, point toward the Contract. Both implementations depend upon Contract but in different contexts: delegation vs implementation.

The Contract is a Natural Barrier between Consumer Business Logic and Provider Contract Implementation. They do not know about nor depend upon each other. The Contract is a Seam allowing the design and implementation of each to proceed independently by different developers or teams. Their only implicit dependency is the shared Contract.

The diagram doesn’t indicate how the Consumer Business Logic obtains a reference to the Provider Contract Implementation. I prefer a Configurer that creates a Provider Contract Implementation and injects its reference into the Consumer Business Logic. The Configurer is out of scope for this topic, but I will include it in a subsequent diagram.

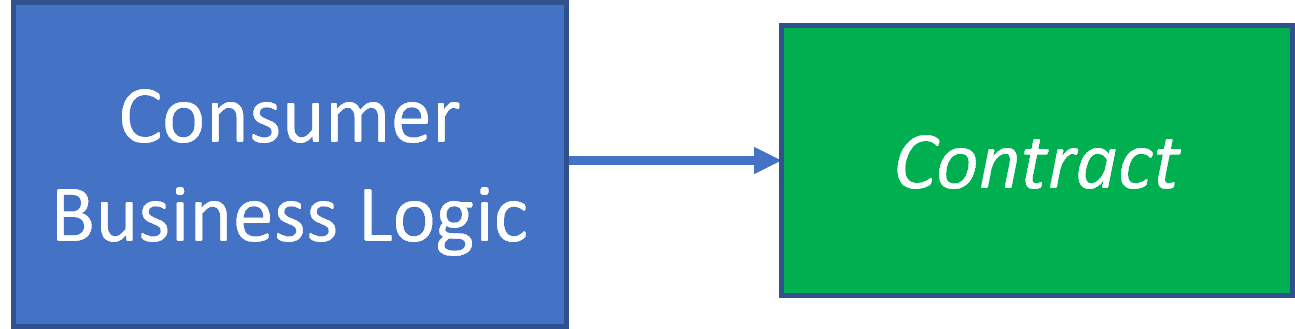

Consumer View

The Consumer’s known world looks like this:

Therefore, the Consumer developers can implement and test the Consumer Business Logic in isolation and emulate the Contract behavior in the Contract Test Double based upon their interpretation of Contract behavior.

Provider View

The Provider known world looks like this:

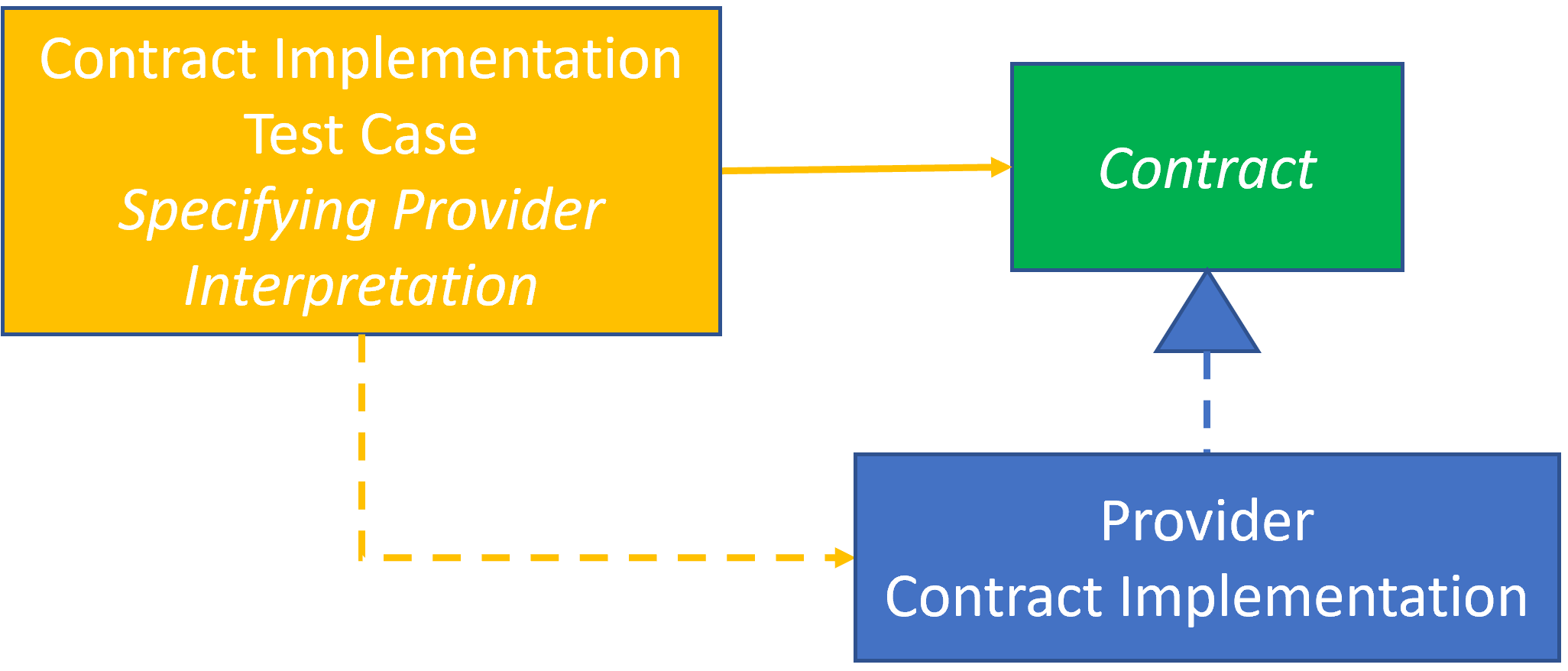

Therefore, the Provider developers can implement and test the Provider Contract Implementation in isolation with their Contract Implementation Test Cases, which specify Contract behavior based upon their interpretation.

The Provider Contract Implementation probably has its own dependencies, which will require its own Test Doubles. I have chosen not to include them in this example for simplicity.

Potential Disconnect

But there’s a possible disconnect. How do we know that the Consumer and Provider have the same interpretation of Contract behaviors? How do we know that the Test Doubles are emulating the Contract with the same behaviors that the actual implementations in production will be using? The Consumer tests could be based upon false premises and rendering false positive results.

I contemplated this possibility in How Do We Know That Emulated Test Double Behavior Is Accurate? A well-defined Contract shouldn’t contain too much ambiguity, but what if the Contract contains elements that are more dynamic, such as Strings or JSON structures? The Contract might specify the String format or JSON structure, but how do we know that the Provider has honored that specification? What if the Test Doubles emulate the dynamic data format and structure correctly, but the Provider does not honor the Contract description? What if the Provider honors the Contract description, but Consumer has misinterpreted it when emulating the Test Doubles?

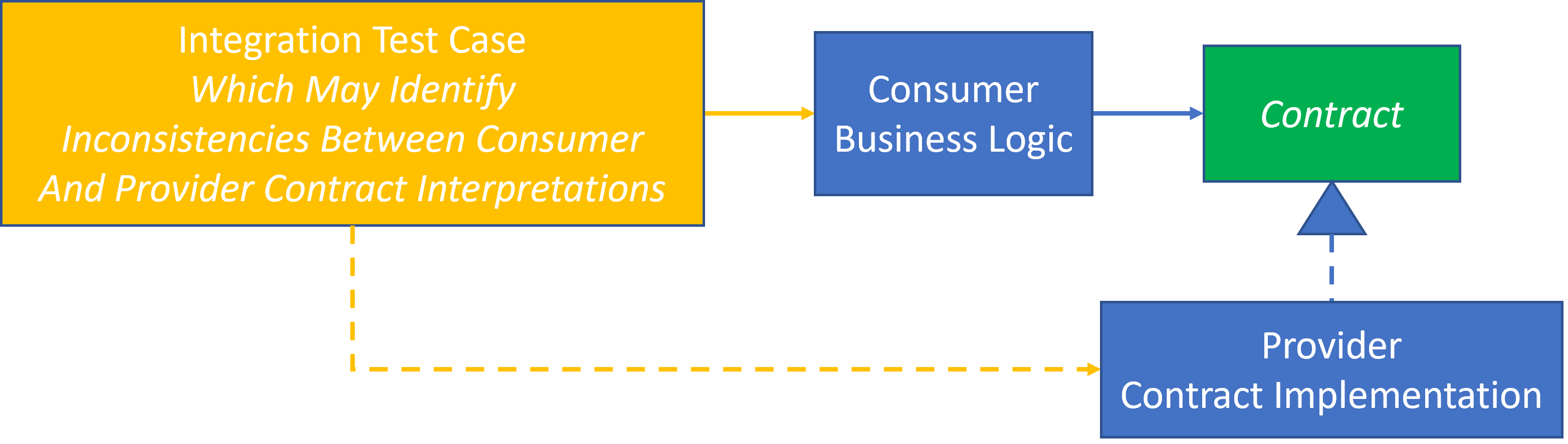

Integration Testing

Integration Testing can help identify Contract consistency issues. This diagram integrates both elements into the same test:

There is no Test Double for the Contract, since this test resolves the reference with the Provider Contract Implementation.

NOTE: If Provider Contract Implementation had its own dependencies, then the Integration Test Case would need to include them as well.

While this would help identify any interpretation differences about the Contract between the Consumer and Provider it comes at several costs:

- Integration testing probably isn’t going to happen until both implementations have matured which means that any inconsistencies might occur later making their resolution more costly than had they been identified earlier.

- Since integration testing won’t cover all scenarios, the entire set of Contract behaviors may not be confirmed. A lurking inconsistency might only be realized in production.

- If an inconsistency is found, it will take some debugging, since it may not be obvious where the Contract inconsistency resides.

Contract Alignment

Can we identify Contract issues sooner than through Integration Testing?

Throughout this Automated Testing series, I have advocated using tests as verifiable specifications for implementation behaviors within our own code. But Consumers can use tests for more than just their own implementations. They can use tests as verifiable specifications for Contracts implemented by Providers, that is, Contract-Driven Customer Testing.

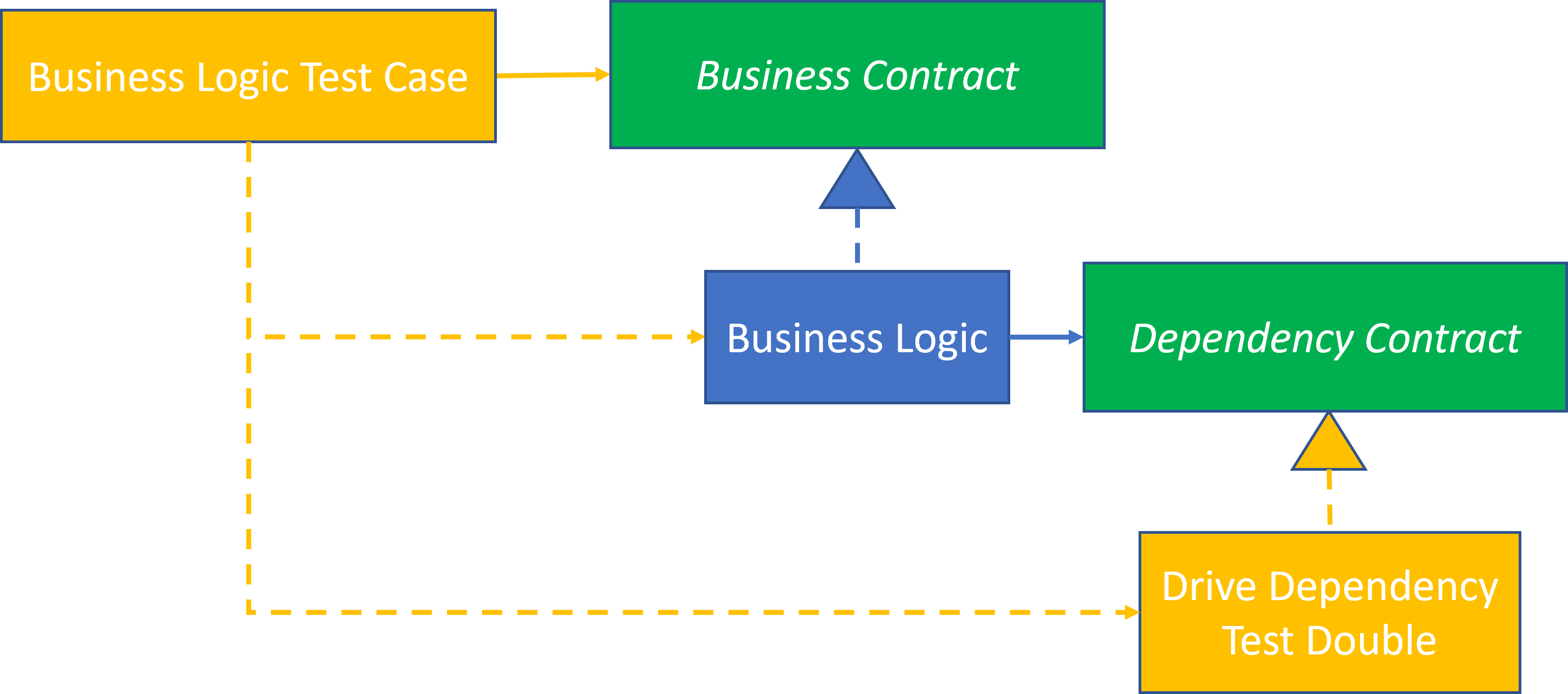

Test Doubles still need to emulate dependency behaviors accurately. However, we can use CDC Testing techniques to codify that the production dependency behavior matches our emulated Test Double behaviors. We still must confirm that our Test Doubles are emulating confirmed dependency behaviors, but with CDC Testing we have more confidence that our assumptions about dependency behavior are accurate.

Here’s what it looks like:

This is structurally identical to the Provider’s unit tests, but it’s more than just a few additional tests.

The value in creating Consumer-Driven tests executed by the Provider is in the communication that it fosters between Consumer and Provider.

Revisiting a phrase from the Microsoft document:

CDC tests confirm a shared understanding documented in a “contract”. Contracts are agreed between consumer and provider …

CDC Testing forces Consumer and Provider to converge upon a shared understanding of the Contract. The test artifacts codify their shared understanding in a verifiable way.

Even though the Consumer drives the tests, the Consumer probably can’t write them in isolation. The Consumer might provide Acceptance Criteria, and the Provider team would write the actual tests, which was the case in Bob Martin’s story in the Introduction. The implementation may have dependencies, which will require Test Doubles in the test. The Provider team will know these details.

The Provider Driven Contract

The Consumer/Provider partnership in driving the Contract won’t always be a kumbaya moment. I can think of several scenarios where the Contract specification might reside more with the Provider than the Consumer:

- Multiple Consumers – Most Providers will have multiple Consumers, and each Consumer will want its own bespoke Contract. The Provider will need to design a Contract that satisfies their Consumers as a whole, but the Provider won’t be able to create a bespoke Contract for each.

- Late Consumer – The schedule may force the Provider to define the Contract before there were any Consumers available for consultation. I requested a Contract update on a past project. My Provider, a coworker on another team, told me it was not possible. I should have made the request during the design review. I kindly pointed out that the design review happened several months before I had joined the company. This company practiced the Waterfall Methodology and used a layered architecture designed from the bottom up. Low-level decisions were locked into place prematurely. We didn’t realize it at the time, but this was the exact opposite of Clean Architecture’s advice to delay decisions as long as possible.

- External Provider – The Provider is external to your organization and may not even know you exist. They may be a major vendor. They may have hundreds of Consumers. They are unlikely to coordinate with you as a Consumer other than provide API documentation and if you’re lucky some customer technical support, both of which might vary widely in completeness and quality.

Regardless of the scenario, the Provider is unlikely to allow the Consumer to drive the Contract nor will the Provider accept Consumer-provided tests.

Consumer And The Provider Driven Contract

Do not despair. The Consumer can protect itself from the Provider-Driven Contract by using the Adapter or Façade design patterns.

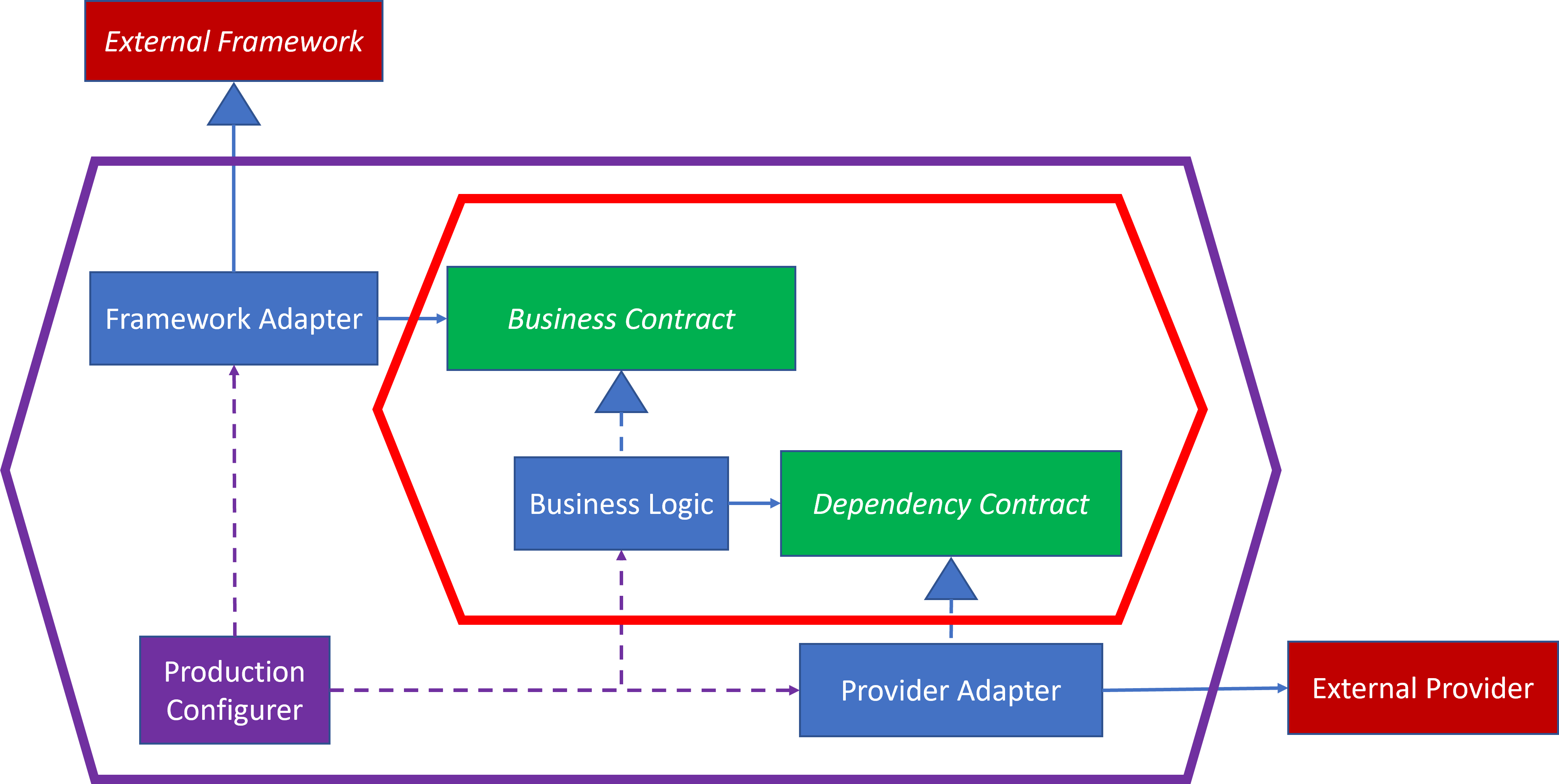

We can see this with Adapters within the Hexagonal Architecture design:

The Hexagonal design shows how the Business Logic only depends upon its Business Contract and Dependency Contract. The Business Logic is cocooned and isolated from external elements, since it has no dependency or knowledge beyond its Contracts. The Adapters are the connective elements that allow the Business Logic to interact with Externals without depending upon Externals directly.

Even if the Consumer can’t directly use CDC Testing to drive the shared Contract, or force Providers to run any Consumer tests, the Consumer can still leverage CDC Test concepts.

Let’s examine each implementation with respect to its own testing. I’ll start in the middle of the Hexagonal design, move to the upper left and finish with the lower right.

Business Logic

This is the entire Business Logic’s known world:

Since the Contracts are defined within the context of the application, this is easy to test:

CDC Testing is not needed in this scenario.

Framework Adapter

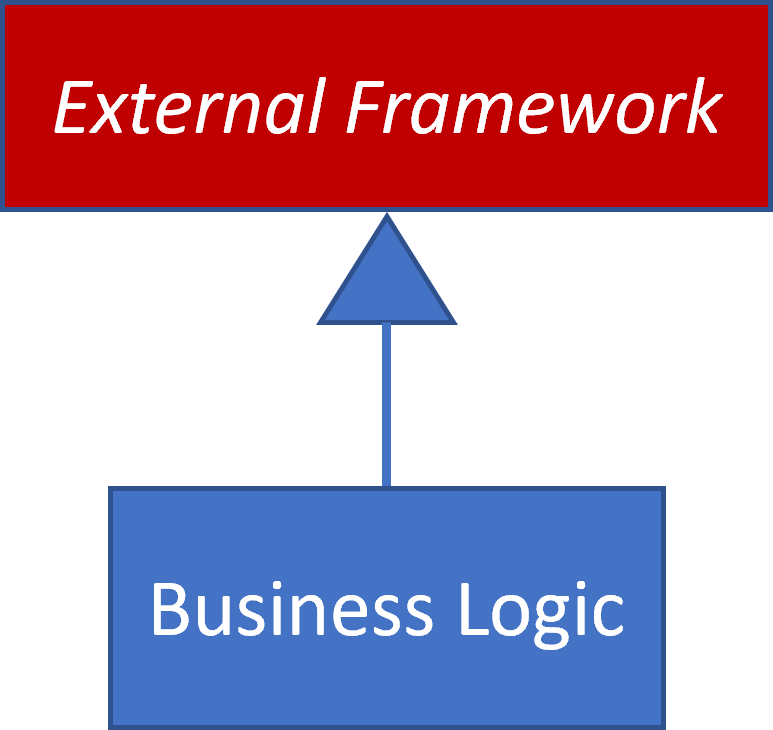

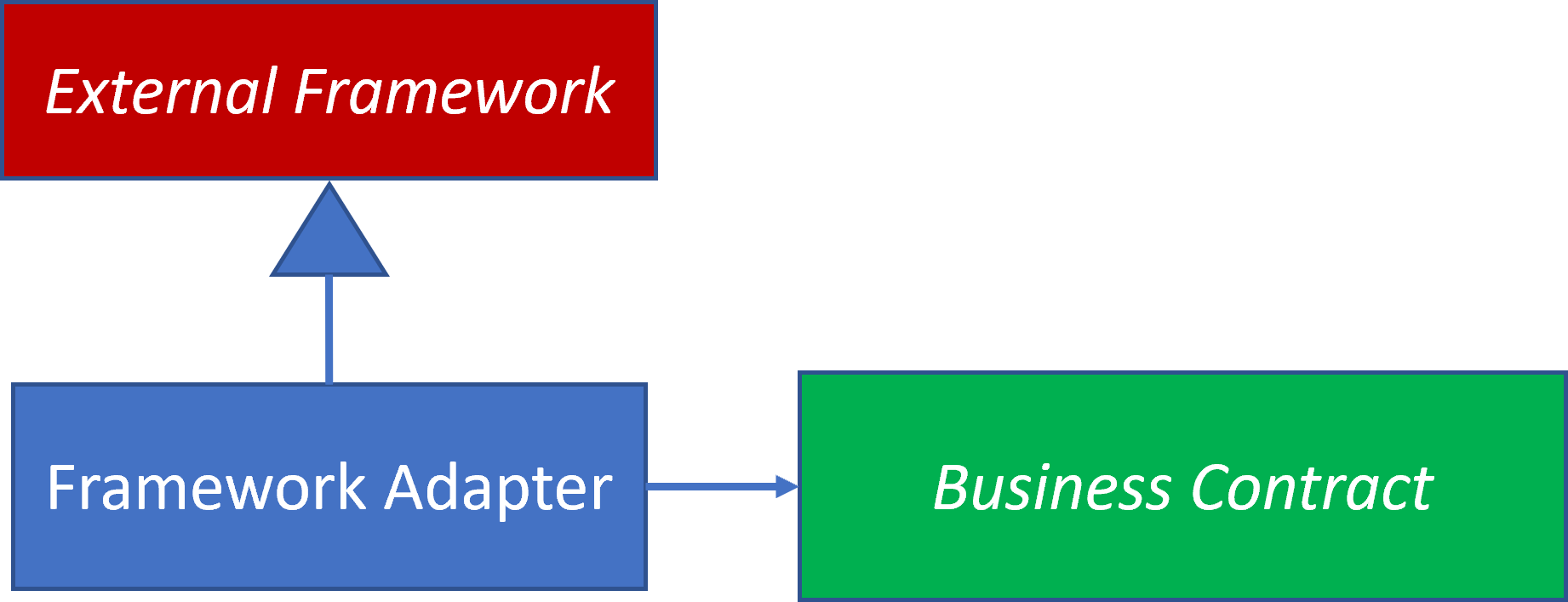

The External Framework is an external dependency. Frameworks are a tricky thing. They can do a lot for you, but they control the show. Let’s consider this naïve design:

It’s straightforward. It’s clean. It’s simple. However, the Business Logic has knowledge of and depends upon the External Framework, but knowledge and dependency is not reciprocal. If the External Framework modifies its terms, it could have devastating effects upon the Business Logic.

This is not a relationship of equals. The framework is dominant in the relationship. It makes most of the decisions. If the framework changes the nature of the relationship, then any of its partners must submit to those changes.

You must understand that when you marry a framework to your application, you will be stuck with that framework for the rest of the life cycle of that application. For better or for worse, in sickness and in health, for richer, for poorer, forsaking all others, you will be using that framework. This is not a commitment to be entered into lightly. ― Robert C. Martin, Clean Architecture

I’ve heard Bob phrase this more succinctly as: Don’t marry the framework, but you can date it; however, I can’t find a confirmed source for the entire phrase.

This means that while we need to work with Frameworks, we should be careful not to allow our application logic to become too tightly coupled to them. When I first heard Martin’s warning, I wasn’t exactly sure what he meant by “dating the framework.” I have come to believe that an Adapter allows the application to date the Framework without the application having to marry it. Bob provides more context, without the matrimonial context, in Framework Bound.

The Framework Adapter depends upon the Framework, but its limited responsibility is to delegate any Framework required behaviors to the Business Contract. The Adapter acts as an Anticorruption Layer keeping the Framework dependencies at bay. Adapters tend to be relatively small, since their main responsibility is to translate Framework concepts into Business Contract concepts. Any Framework updates would hopefully be limited to the Adapter’s relatively small implementation.

This is the entire Framework Adapter’s known world:

The External Framework and the Business Contract have no dependencies or knowledge of one another. If the External Framework changes its Contract, then ideally, the only impact is upon the Framework Adapter and not the Business Contract.

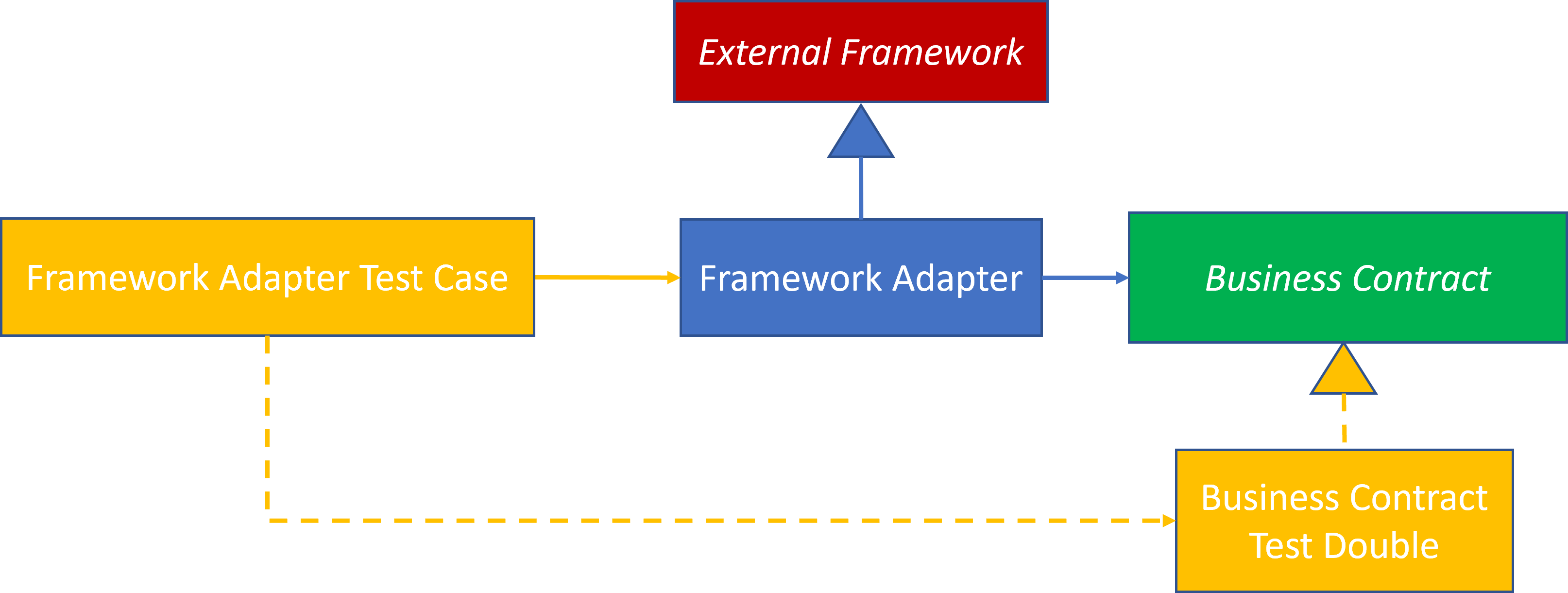

A design to test the Framework Adapter might look something like this:

I’ve indicated that Framework Adapter Test Case interacts with Framework Adapter, since it may not have access to the External Framework elements. If it does, then it could interact with it. Business Contract Test Double emulates Business Logic so that we can confirm Framework Adapter behavior.

This will test most Adapter mapping behavior from the Framework to the Contract; it’s not quite CDC Testing. While we may know some Framework behaviors from documentation or previous experience, it may be difficult to replicate it in this type of test.

Provider Adapter

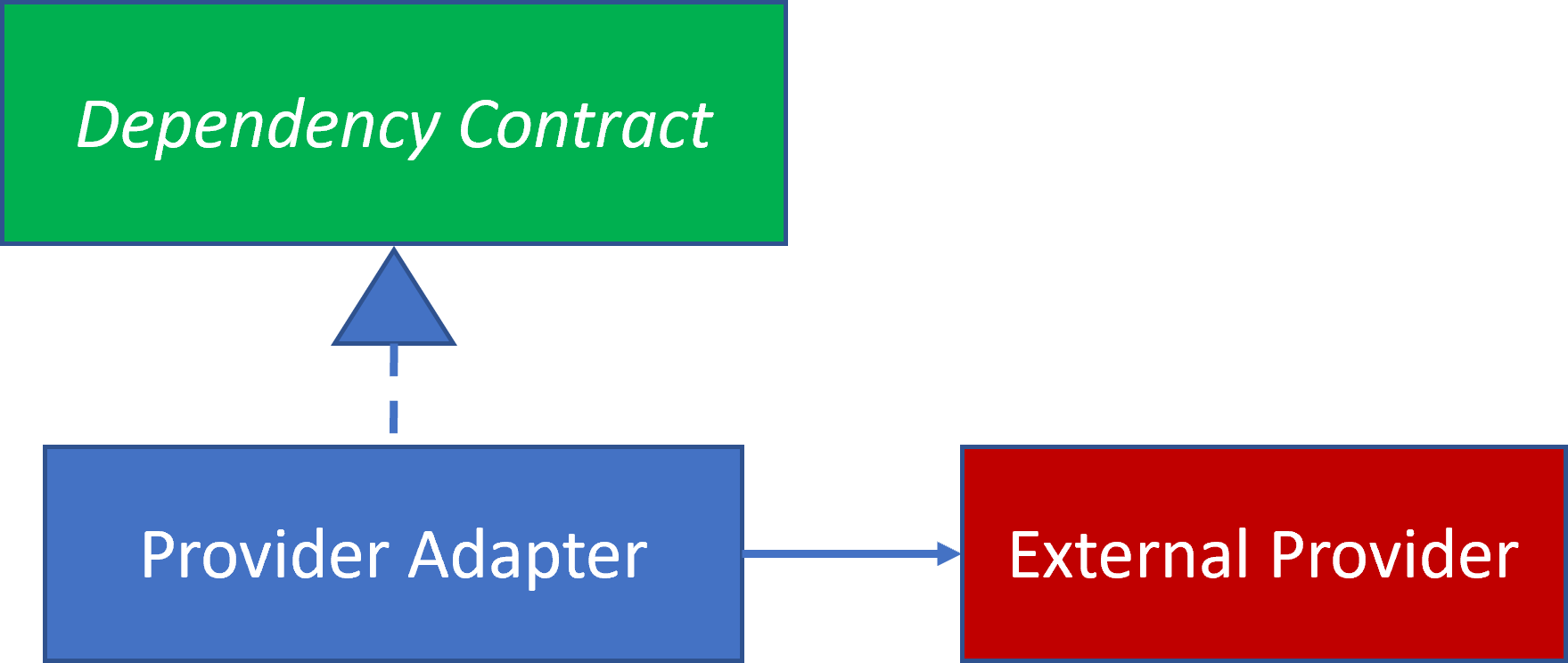

We don’t want Business Logic to have a direct dependency upon an External Provider either, so an Adapter will work here as well.

This is the entire Provider Adapter’s known world:

Testing isn’t as convenient as the two previous cases. External Provider is an external dependency, which makes it difficult to incorporate in a Unit Test. The Provider Adapter’s main purpose is to separate the Business Logic from external dependencies, but it cannot separate itself from those external dependencies. Therefore, we cannot easily unit test the Provider Adapter.

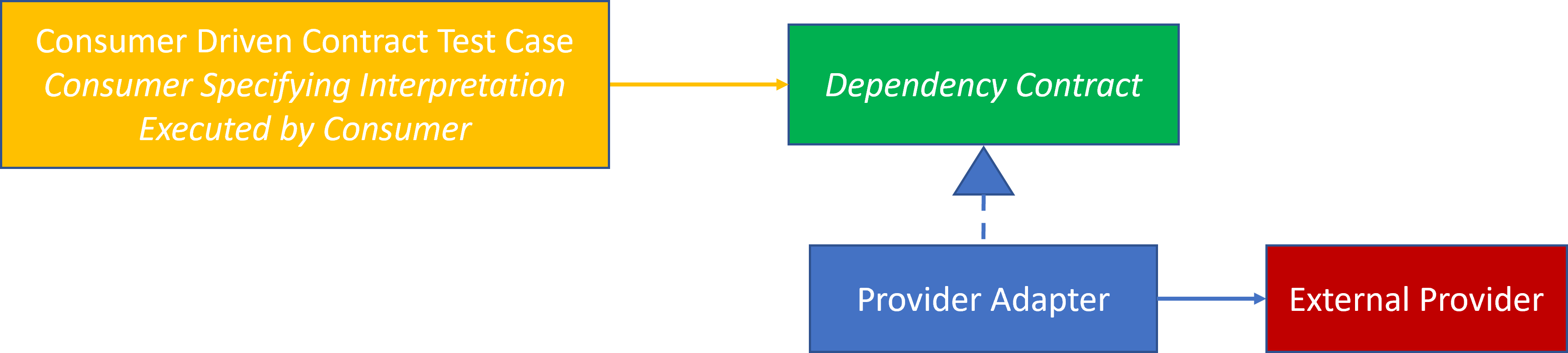

We can use the concept of CDC Testing but with one minor tweak. The Provider won’t run any tests; the Customer will run them. We have two basic test designs. Both designs interact with the External Provider confirming its behaviors. Since the External Provider is an external dependency, these tests will be slow, more difficult to set up and potentially costly. Ideally, they should be executed in a test sandbox so that they don’t affect anything in production.

Given their limitations, they should not be part of the traditional test cycle. Each situation is unique, but maybe we may not want to run these tests more frequently than nightly or possibly weekly. The External Provider probably won’t change behavior often, but when it does, we want to know, so we can adjust as needed.

This test design tests the External Provider:

This test design tests the Provider Adapter and the External Provider:

Why Bother?

This level of testing is optional, so why bother? I heard this story second hand from a coworker, so I may not have accurate details. A previous employer had a strategic partner as an external Provider. The Provider changed their Contract. I don’t know if they changed the Contract’s syntax, semantics or both. Regardless, their change affected our product’s behavior for our users. We did not know about the Provider’s update. I don’t know if it’s a case that we didn’t notice the notification in their release notes, or whether the update fell upon the wrong ears, or whether they didn’t notify us thinking that it didn’t matter.

We learned of the update when our customers started to complain that our product was not working as expected. We looked a bit foolish and incompetent, since we didn’t have any idea what was wrong.

Diagnosis took additional time, since we first needed to rule out user error. When we were able to reproduce the behavior ourselves, we suspected our own code. Once we ruled that out, we identified the change in Contract behavior with our external partner Provider. We could accommodate their new Contract behavior, but by then the cost of unhappy customers and the frustration of our own customer support staff during the identification, diagnosis and remediation phases had done their damage.

Now consider the same scenario, but instead we had several tests that confirmed the Provider’s Contract nightly. We would have identified a change in Provider behavior no more than a day after being released. We could have contacted our Provider for additional information. We could have notified our customer support team and possibly even our customers that we had a known issue with partner-related features, and we were working on it. We could have gotten ahead of the problem.

We would have known of a potential issue within a day. Identification and diagnosis would have mostly been eliminated, since we would have known that the Provider had updated their behavior. Remediation may have taken about the same amount of time once identified, but we would have gotten a jump on the problem, since it would have been identified sooner.

Summary

Consumer-Driven Contract testing isn’t just a testing technique—it’s a mindset shift that redefines how services collaborate. By letting consumers specify the expectations and enforcing them through shared contracts, CDC builds trust across teams and promotes resilient, loosely coupled systems. This article explores the principles behind CDC and how it supports agile development in distributed environments.

References

- What is consumer driven contract testing? - API Hub

- Consumer-Driven Contracts - Blog by Ian Robinson

- Introduction to Pact - Getting Started Guide to Pact, which features Consumer Testing.

- My thoughts and notes about Consumer Driven Contract Testing - Blog by Murat K Ozcan

- Consumer-Driven Contracts - Brief overview from Thoughtworks

- What is Consumer-Driven Contract Testing (CDC)? - Overview from Hypertest

- Consumer Driven Contract Testing - What , Tools & Example - Blog by Lewis Prescott

- What is contract testing? - Video by Daniel Knott

- What is Consumer Driven Contract (CDC)? How to use Spring Cloud Contract Testing? - Video by Jasvinder Singh Saggu

- Consumer Driven Contract Testing with Pact - Backend - Video by Kirill Ushakov

- Google Search for Consumer Driven Constract Testing

- YouTube Search for Consumer Driven Contract Testing